Why the Universe Might Be More Ordinary Than We Think and What That Means for Finding Alien Civilizations

A new study by Dr. Robin H. D. Corbet, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and a senior research scientist at the University of Maryland, offers a surprisingly grounded explanation for one of humanity’s biggest puzzles: why we haven’t found signs of extraterrestrial technological civilizations, often called ETCs. The research introduces the idea of “radical mundanity” — a principle that suggests the universe, and any intelligent life in it, might simply be unremarkable rather than extraordinary.

Dr. Corbet’s paper, posted to the arXiv preprint server in late September 2025, explores how this concept could solve the Fermi Paradox, the long-standing question that asks: “If intelligent life is common, where is everybody?” His conclusion is both humbling and oddly comforting — that there may be other civilizations out there, but their technology and behavior are mundane enough that we just haven’t noticed them yet.

The Core Idea: Radical Mundanity

The principle of radical mundanity is an extension of the Copernican principle, which says that Earth and humanity are not in a special or unique position in the universe. If we apply that same logic to alien civilizations, then it’s reasonable to assume that they too might be average in both capability and ambition.

This means that extraterrestrial civilizations could exist, but their technology might not be advanced enough to make them easily visible across interstellar distances. In other words, we shouldn’t expect galaxy-spanning empires or massive beacons broadcasting their presence — because maybe, just like us, they haven’t built anything so spectacular.

Dr. Corbet argues that the most straightforward explanation for the Fermi Paradox might simply be that there are a modest number of civilizations in our galaxy, and they are operating at modest levels of technology.

Revisiting the Kardashev Scale

To understand this better, Dr. Corbet refers to the Kardashev scale, a method proposed by the Russian astrophysicist Nikolai Kardashev in 1964 to categorize civilizations based on their energy use:

- Type I civilizations harness all the energy available on their home planet.

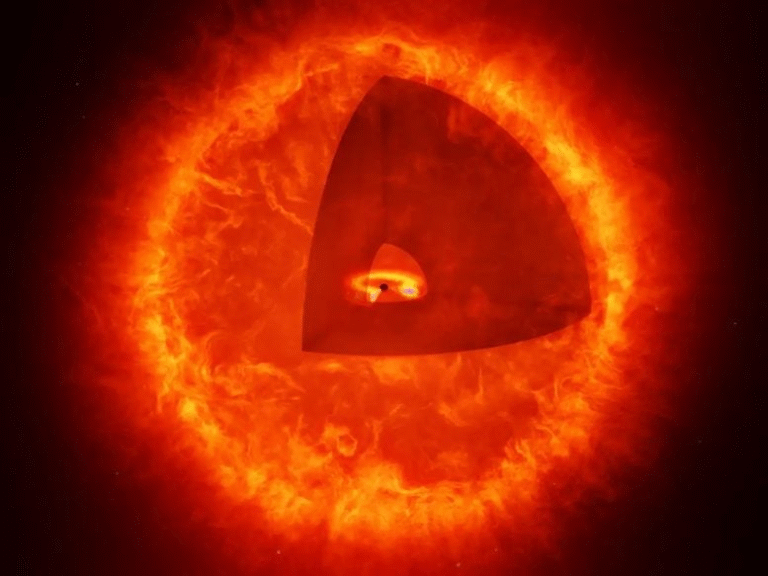

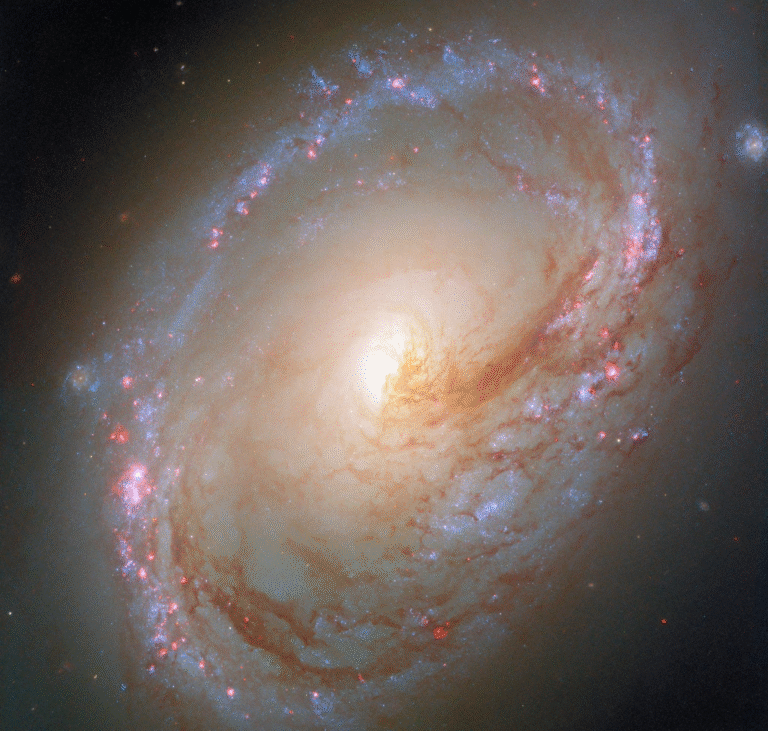

- Type II civilizations can capture the energy output of their entire star, possibly through structures like Dyson spheres.

- Type III civilizations use the energy of their entire galaxy.

According to Corbet’s analysis, our expectations that there should be Type II or Type III civilizations visible in the Milky Way might be unrealistic. If intelligent life forms elsewhere tend to develop technology in a similar, gradual, and constrained way as humans, then it’s possible most ETCs never reach those extreme levels. Instead, they might linger at something like a Type 0.8 or Type I level — advanced compared to us, but still limited in scale.

This would naturally make them much harder to detect. Their radio signals could be weak, their use of resources modest, and their impact on their environments subtle.

Four Hypotheses That Might Be Wrong

To dig deeper, Corbet laid out four major hypotheses that try to explain the Fermi Paradox — and argues that at least one of them must be false:

- There are many civilizations with very high technology.

- There are very few civilizations with very high technology.

- There are many civilizations with mundane technology.

- There are very few civilizations with mundane technology.

He concludes that the real universe may not fit neatly into any of these extremes. Instead, it’s likely that a modest number of moderately advanced civilizations exist. They could be slightly ahead of us technologically but not enough to make them easily noticeable through traditional detection methods.

The Limits of Galactic Expansion

Another part of the study examines why we haven’t seen signs of galactic colonization — such as robotic probes or interstellar megastructures.

Corbet notes that the idea of civilizations spreading across the galaxy with fleets of self-replicating robots has long been a popular solution to the Fermi Paradox. But in his view, this assumes both the motivation and technological capability to do so, which might not exist in reality.

He suggests that civilizations, no matter how advanced, might be limited by energy constraints, social priorities, or even disinterest in large-scale expansion. They could also face ecological or existential risks that prevent them from developing galaxy-spanning technologies.

Even if such projects are physically possible, they might not be culturally or economically sustainable, meaning that the lack of evidence doesn’t necessarily mean there’s no one out there — just that their ambitions are more local.

What This Means for SETI and Future Searches

If the universe is filled with “mundane” civilizations rather than spectacular ones, our current search methods may be too narrow. The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has often focused on looking for high-powered beacons, mega-engineering projects, or unmistakable radio signals.

However, Corbet’s work implies that the signs of life might be much quieter — such as low-level radio “leakage” from communication systems, or subtle technosignatures that mimic natural phenomena.

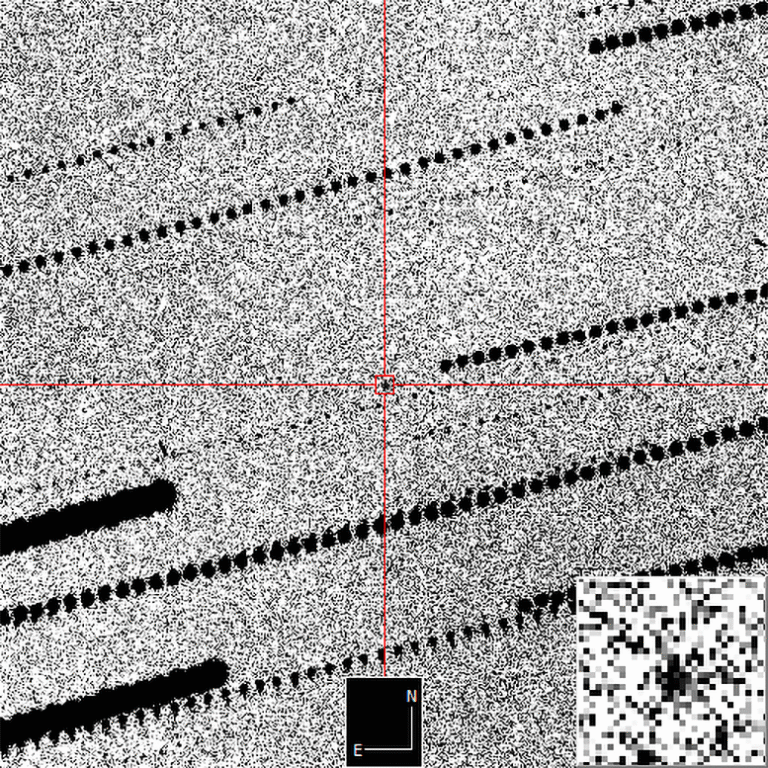

He mentions that future radio observatories like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) could be sensitive enough to detect such weak signals. The SKA, when fully operational, will be the world’s largest radio telescope, capable of spotting faint emissions that current instruments might miss.

This is a hopeful twist: if civilizations are indeed ordinary and relatively nearby, then the first detection of an alien signal might not be centuries away — it could happen within a few generations of technological progress.

The Fermi Paradox and Other Possible Explanations

The Fermi Paradox has intrigued scientists for decades. Originally proposed by Dr. Enrico Fermi, it asks the deceptively simple question: If intelligent life is common in the universe, why haven’t we found any evidence of it?

Over the years, many explanations have been proposed:

- Life is rare. Civilizations might destroy themselves or hit a technological ceiling.

- Life is common but quiet. This is the so-called Dark Forest hypothesis, where civilizations hide to avoid being detected by potentially hostile others.

- They exist, but we haven’t recognized them. Maybe they use technologies or communication methods beyond our understanding.

Dr. Corbet’s “mundane universe” fits somewhere between these possibilities. It doesn’t assume extinction or paranoia — just ordinary limitations. Civilizations might exist, but they’re not doing anything big enough to make them stand out.

Why This Idea Feels Refreshingly Realistic

The concept of a “mundane universe” might sound disappointing at first — after all, it suggests we’re not on the verge of meeting hyper-intelligent galactic neighbors. But in another sense, it’s reassuring. It paints a universe that’s stable, restrained, and understandable.

Rather than imagining either a silent void or a galaxy teeming with super-beings, Corbet’s approach invites a middle ground — a cosmos where civilizations rise, develop modestly, and perhaps coexist quietly, separated by vast distances and limited by practical realities.

And for humanity, that’s not a bad thing. It means that as our technology improves, especially in radio astronomy and signal processing, the first detection of extraterrestrial intelligence could come not from a blinding beacon across the stars, but from something subtle — a faint whisper that confirms we’re not alone, after all.

The Bigger Picture

Studies like this remind us that the search for intelligent life isn’t just about finding others — it’s about understanding ourselves. If the universe tends toward the ordinary, then perhaps our own story is part of that pattern.

We may be typical, not special — and that’s a profound realization. It means intelligence and curiosity might not be rare, just quietly common and hard to notice.

In the end, Dr. Corbet’s “radical mundanity” gives us a new lens through which to view the cosmos: not a stage for spectacular alien empires, but a calm, sprawling landscape filled with civilizations quietly getting on with their lives — much like us.

Research Reference:

Robin H. D. Corbet, A Less Terrifying Universe? Mundanity as an Explanation for the Fermi Paradox, arXiv (2025).

https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.22878