Zoo-Bred Giraffes Have Lost Their Conservation Value as Decades of Hybrid Breeding Erode Their Wild Lineages

A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Morfeld Research & Conservation has revealed a worrying truth about giraffes kept in American zoos and private collections. What were once seen as valuable “assurance populations”—genetic backups that could help repopulate dwindling wild giraffes—have lost much of their conservation potential due to decades of hybridization across different giraffe species.

The research, published in the Journal of Heredity, analyzed the DNA of 52 captive giraffes in North American zoos and ranches and compared them with 63 wild giraffes representing all four recognized species. The results showed that most captive giraffes are not genetically pure members of any single species. Only eight individuals closely matched a single wild species, while the rest were genetic mixes of two or even three species.

The Study and Its Findings

The research team, led by Professor Alfred Roca from the University of Illinois’ Department of Animal Sciences, wanted to evaluate whether captive giraffes could genuinely serve as a genetic backup for wild populations. The idea of assurance populations is straightforward: if wild populations crash due to habitat loss, poaching, or disease, genetically healthy captive animals could help restore them.

However, this concept only works when the captive animals accurately represent their wild counterparts. Unfortunately, the study found that North American giraffe collections no longer reflect the genetic makeup of wild populations. Instead, decades of interbreeding among giraffes from different regions and subspecies have created animals with mixed DNA, blurring the once-clear boundaries between species.

To understand the extent of the problem, the scientists used advanced DNA sequencing and genomic comparison techniques. They looked for how closely the genomes of captive giraffes matched wild ones. The findings were stark: hybridization was so widespread that the majority of captive giraffes can no longer be linked cleanly to any one of the four species—the northern giraffe, southern giraffe, Masai giraffe, and reticulated giraffe.

How Did Hybridization Happen?

The problem appears to trace back to breeding practices that prioritized animal management convenience and temperament over genetic purity. In 2004, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) introduced a policy treating giraffes in its care as a single “generic” breeding population. Before this change, there had been an attempt to maintain distinct breeding programs for individual subspecies.

However, the AZA recognized that hybridization was already widespread, and continuing to breed separately might have been impractical given the limited numbers of pure individuals. The 2004 decision effectively ended any effort to maintain genetic distinctness within captive giraffes, accelerating hybrid mixing.

The researchers also noted that some hybridization may have occurred even earlier, possibly involving a wild reticulated giraffe that was itself a rare natural hybrid. Still, the majority of the interbreeding appears to have been human-induced through zoo breeding programs that didn’t fully account for genetic origins.

Why Hybridization Matters for Conservation

At first glance, the existence of hybrid giraffes may not seem like a major issue—after all, they’re still giraffes. But in conservation biology, genetic integrity matters enormously. Each giraffe species has evolved unique traits suited to its environment, such as coat patterns, behaviors, and ecological preferences. Mixing species through hybridization can erase these adaptations, leading to animals that no longer represent any particular population found in the wild.

This is a serious problem for conservation planning. If captive giraffes are hybrids, they cannot safely be used for reintroduction or genetic reinforcement of wild populations without risking further genetic dilution. The whole idea of assurance populations—insurance against extinction—depends on having genetically accurate representatives of wild species.

Currently, the global giraffe population stands at around 97,500 individuals spread across 21 African countries, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). All four species are listed as vulnerable, and some specific populations are critically endangered. Losing the conservation value of captive giraffes means losing an important backup for these struggling wild herds.

Recommendations from the Researchers

The study’s authors recommend that zoos and breeding centers take immediate steps to phase out hybridized giraffes from conservation breeding programs. These animals can still serve important roles as educational ambassadors, helping people connect with wildlife. However, when it comes to maintaining genetically representative populations, the focus must shift to individuals that align closely with wild species genetics.

One possible solution, though challenging, would be to restart breeding programs using fresh wild genetics. This could mean importing new giraffes directly from Africa, though physically transporting such large animals is logistically difficult and costly.

A more practical approach, according to Kari Morfeld of Morfeld Research & Conservation, would be to use reproductive technologies such as artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization (IVF), and embryo transfer. These techniques could allow scientists to move genetic material—semen and embryos—instead of live animals. Such methods are already routine in livestock breeding and could be adapted for giraffes with the right expertise and collaboration.

The researchers also emphasize that genetic restoration of captive giraffes is only part of the solution. Real conservation success depends on protecting and restoring wild populations in Africa, many of which are losing habitat and facing poaching pressures. To succeed, conservationists, governments, and zoos will need to build trusting partnerships that share knowledge, resources, and benefits among all stakeholders.

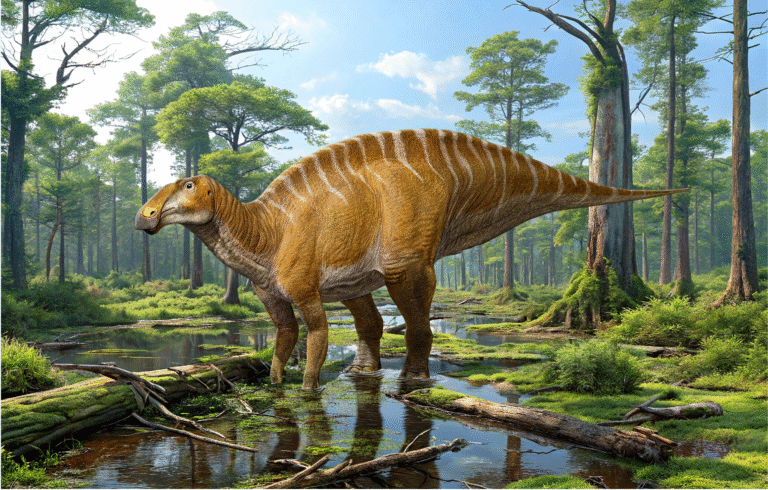

Understanding Giraffe Species and Their Conservation Status

For decades, scientists believed all giraffes belonged to one species, Giraffa camelopardalis, with nine subspecies scattered across Africa. But recent DNA research has overturned that assumption. Today, scientists recognize four distinct giraffe species that rarely interbreed in the wild:

- Northern Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) – Found in scattered populations across Central and East Africa; includes the critically endangered Kordofan and Nubian giraffes.

- Reticulated Giraffe (Giraffa reticulata) – Known for its striking net-like pattern, found mainly in northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia.

- Masai Giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi) – Native to Tanzania and parts of Kenya, with a unique irregular patch pattern.

- Southern Giraffe (Giraffa giraffa) – Common in southern Africa, including Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa.

The discovery that these are separate species changed how conservationists view giraffes. Instead of one large, stable population, we now understand there are four smaller, vulnerable species, each facing distinct threats. For instance, the northern giraffe has lost over 90% of its historical range.

What This Means for Zoos and Conservationists

The new study sends a strong message to zoos worldwide: if captive giraffe programs are to contribute meaningfully to conservation, genetic management must become a top priority. Breeding decisions should no longer be based merely on animal compatibility or physical traits. Instead, DNA testing should guide which individuals breed to preserve authentic species genetics.

Zoos also need to be transparent about the genetic composition of their giraffe populations. Collaboration between North American, European, and African institutions will be crucial to rebuilding genetically pure assurance herds that can someday serve real conservation roles.

While hybrid giraffes can continue to inspire and educate millions of visitors, they can no longer be considered reliable backups for the wild. The solution lies in combining modern genomic science, reproductive technology, and international cooperation to ensure that the world’s tallest animals continue to thrive—not just in enclosures, but in their natural habitats across Africa.

Research Reference:

Genomic Assessment of Giraffes in North American Collections Highlights Conservation Challenges – Journal of Heredity (2025)