Modern Farming Is Threatening Europe’s Protected Areas While Traditional Practices Help Keep Nature Alive

New research has revealed a clear truth about the future of Europe’s most important natural reserves: modern, intensive agriculture is putting biodiversity inside protected areas at serious risk, while traditional low-intensity farming could actually be one of the keys to saving it.

The study, carried out by researchers from the University of Turku in Finland and Tour du Valat in France, examined how different types of farming are influencing the health of ecosystems within Natura 2000, the world’s largest network of protected areas. Natura 2000 was created by the European Union to safeguard species and habitats of community importance. Despite this, a shocking 80% of these habitats are currently in an unfavorable state of conservation, according to national reports.

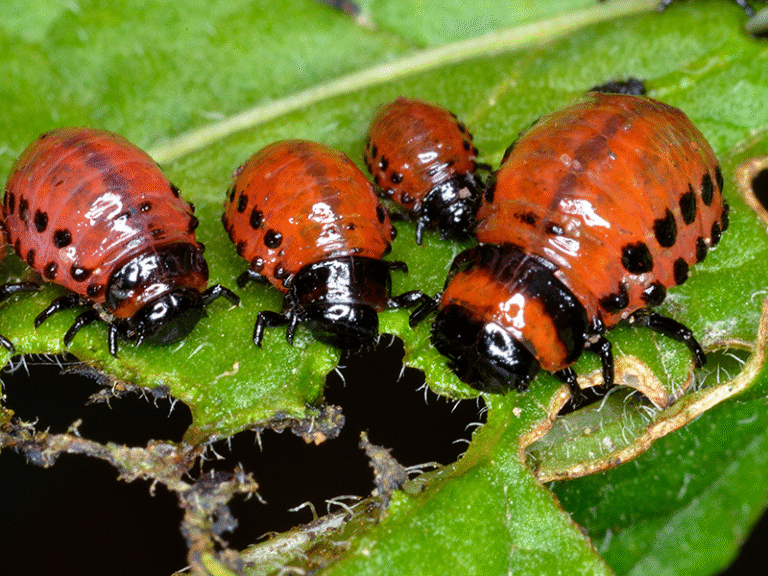

The research, published in Conservation Biology (2025), involved a large-scale survey of protected area managers across Europe. The results paint a sobering picture: the intensification of agriculture—through pesticide use, overgrazing, hedgerow removal, and heavy fertilizer application—is the main threat to biodiversity even within these supposedly protected zones.

How Modern Agriculture Is Affecting Biodiversity

The modern model of European agriculture relies heavily on inorganic fertilizers, pesticides, monocultures, and new crop varieties, including winter crops that alter natural cycles. While these practices have increased short-term productivity, they have also driven habitat loss, degraded soil health, and disrupted food chains.

Protected area managers surveyed in the study reported that these pressures are not confined to farmlands outside Natura 2000 sites—they are creeping into the protected zones themselves. In many cases, local managers feel powerless to counteract the impact of intensive farming, especially when such activities are tied to national or EU-level subsidies that encourage large-scale production.

The core message from the researchers is straightforward: declaring an area as “protected” does not automatically protect biodiversity. Without active management and engagement with local communities and farmers, many sites continue to face degradation despite their official status.

Traditional Farming Could Be the Unexpected Solution

Interestingly, the study found that not all agricultural activity is bad news for conservation. In fact, traditional, low-intensity farming methods can play a vital role in maintaining biodiversity.

Practices such as extensive grazing, where cattle or sheep graze lightly over wide areas, and seasonal mowing, which prevents grasslands from turning into shrubland, are actually essential to maintaining habitats like European grasslands and marshes. These ecosystems are among the most species-rich environments in Europe, supporting rare plants, insects, and birds that depend on open landscapes.

Researchers note that many Natura 2000 site managers actively promote these traditional methods. The idea isn’t to eliminate agriculture, but to balance human activity and ecological health—something Europe’s older farming traditions often achieved naturally.

Unfortunately, as intensive farming expands and rural economies modernize, these traditional practices are disappearing. Younger generations are less likely to continue extensive grazing or manual mowing, leading to overgrowth, habitat change, and declining biodiversity.

The Funding Paradox of the Common Agricultural Policy

One of the most surprising aspects highlighted in the research is the role of funding mechanisms in perpetuating the problem. Management of Natura 2000 sites often relies on funding from the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)—the same policy that also subsidizes intensive farming across Europe.

This creates a paradox: the EU is funding both biodiversity protection and biodiversity loss through the same instrument. While part of CAP supports agri-environmental schemes that encourage nature-friendly practices, another part provides subsidies for large-scale, intensive production—even within or adjacent to protected areas.

Researchers argue that this contradiction undermines conservation goals. They call for the EU and its member states to align agricultural subsidies with biodiversity outcomes, ensuring that financial incentives do not work against the objectives of Natura 2000.

The Bigger Picture: Biodiversity in Crisis

Across the European Union, intensive agriculture remains the primary driver of habitat degradation. Beyond pesticides and fertilizers, other elements of intensification—like draining wetlands for crop production, converting meadows into monocultures, and removing hedgerows—have stripped away the natural diversity that once supported wildlife.

This is particularly concerning given that Europe has already lost many of its large mammals and migratory birds due to land-use changes. The disappearance of traditional landscapes has also meant the loss of pollinators and soil organisms essential for ecosystem balance.

The European Commission’s own reports show that biodiversity targets set under previous frameworks are far from being met. Many of the biodiversity-friendly measures originally proposed in the European Green Deal were later watered down or removed in 2024, weakening the EU’s ability to meet its conservation promises.

Why Stakeholder Involvement Matters

The study emphasizes that top-down protection measures are not enough. True conservation depends on collaboration among farmers, local residents, scientists, and policymakers. Managers of Natura 2000 sites often face practical limitations—they have to work with limited staff, small budgets, and competing land-use priorities.

To effectively safeguard these areas, managers must have both regulatory authority and community support. Farmers, in particular, are crucial partners. When provided with the right incentives and education, many are willing to adopt sustainable land-use practices that help nature recover.

Such cooperation could also revive rural economies, as eco-friendly farming practices often create opportunities for organic production, eco-tourism, and local branding. These can provide income while maintaining ecological integrity—a win-win scenario for both people and wildlife.

Lessons from the Natura 2000 Network

The Natura 2000 network covers more than 18% of EU land area and is globally recognized for integrating human land use with biodiversity conservation. The principle is that people and nature can coexist, but the reality often depends on how that coexistence is managed.

The new research underscores that effective conservation is dynamic. It requires ongoing monitoring, adaptive management, and a willingness to learn from both successes and failures. Simply placing boundaries on a map isn’t enough—the real work happens in the fields, marshes, and meadows where people live and work.

A Call for Smarter Policies

The study’s authors call for stronger agricultural regulations within and around protected areas, better enforcement of existing rules, and a realignment of subsidies to favor biodiversity-friendly practices. They also urge governments to support traditional farmers who maintain extensive, nature-positive systems.

If Europe truly wants to meet its biodiversity goals, the path forward involves rethinking how agriculture and conservation coexist. Protecting nature isn’t about excluding people—it’s about encouraging the right kind of human presence.

The findings ultimately remind us that healthy ecosystems and sustainable agriculture can go hand in hand, but only if policies, funding, and management all move in the same direction.