Fish in Michigan’s Inland Lakes Are Shrinking, and Scientists Say Climate Change Is to Blame

A new study from the University of Michigan has revealed a surprising and concerning trend in the state’s inland lakes — both young and old fish are getting smaller. Researchers analyzed data from 75 years and nearly 1,500 lakes across Michigan, discovering that many fish species have declined in body size over time. The findings suggest that climate change is a major factor driving this change, altering not only the lakes themselves but also the creatures that live in them.

Long-Term Study Across 75 Years and 1,497 Lakes

The research team, led by Peter Flood, a postdoctoral fellow at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS), examined a vast dataset that documented fish sizes dating back to 1945. The records came from long-term collaborations between the University of Michigan and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR), maintained under the Institute for Fisheries Research.

Thanks to a community science project on the platform Zooniverse, decades of handwritten survey cards were digitized, allowing scientists to track trends that were previously buried in paper archives. This gave them the ability to measure long-term changes in 13 fish species and multiple age groups within each species.

When the data was analyzed, the researchers discovered that out of 125 species-age class combinations, 58 showed significant changes in average fish size over time. Of those, a striking 46 combinations had gotten smaller.

The study’s findings, published in Global Change Biology, highlight that both the youngest and oldest fish within populations have experienced the largest decreases in length. These two age groups play vital roles in maintaining fish populations and healthy aquatic ecosystems.

Why Are Fish Getting Smaller?

The researchers point to climate change as the most likely cause. Warmer water temperatures can directly influence fish metabolism, growth rates, and available habitat. Cold-water species in particular are losing their optimal thermal zones as lakes warm up, leaving them less room to thrive.

At the same time, fish adapted to warmer temperatures—like largemouth bass—are seeing changes too. While these species can tolerate higher temperatures, increased abundance due to favorable conditions may lead to more competition for limited food, resulting in smaller average body sizes.

Another key factor is changes in lake ice cover. Historically, many Michigan lakes experienced ice cover for longer periods, with mass fish mortality events occurring as ice melted in early spring. Now, with shorter and more unpredictable ice seasons, the timing and extent of these natural cycles have shifted. These changes can alter growth patterns and seasonal food availability, further contributing to smaller fish sizes.

How Smaller Fish Affect Ecosystems

Size in fish is not just a matter of appearance or angler satisfaction—it’s fundamental to how lake ecosystems function. Many fish predators are “gape-limited,” meaning they can only eat prey that fits in their mouths. When younger fish are smaller, they become easier targets for predation, potentially reducing the number of fish that survive to maturity.

This creates a ripple effect through the ecosystem. Fewer mature fish can mean fewer spawners, and a smaller genetic pool may reduce the resilience of populations to environmental changes.

Older fish, though less numerous, are often critical for maintaining population stability. They contribute to spawning success, influence social behaviors among younger fish, and help keep ecosystems balanced. When these older fish also shrink, their ability to reproduce effectively and influence younger generations may decline.

Researchers stress that we rarely think about “culture” among fish populations, but there’s evidence that older individuals help sustain learned behaviors—for example, identifying feeding grounds or spawning sites. Losing large, older fish may therefore erode this generational knowledge that benefits entire communities of fish.

Implications for Fisheries Management

These findings are also highly relevant for fisheries management. The Michigan DNR sets size and harvest limits to ensure sustainable fish populations. If climate change is altering fish growth rates and typical sizes, those management strategies may need to evolve as well.

Understanding which age groups and species are shrinking the most gives managers a new tool to anticipate how fish populations will respond to continued warming. For example, regulations might need to be adjusted to account for smaller adult fish or altered breeding ages.

Flood emphasized that this dataset allows fisheries managers to stay ahead of the curve, using long-term evidence to adapt strategies before the impacts become irreversible.

For anglers, this could mean seeing smaller catches in the future, even if fish populations remain stable in number. Beyond recreational concerns, smaller fish can also signal deeper ecological imbalances that deserve attention.

The Power of Historical Data and Museum Collections

One reason this study stands out is the unprecedented scale and duration of its dataset. Few regions in the world have such detailed fish records spanning three-quarters of a century. The digitization effort through crowdsourcing on Zooniverse transformed these old surveys into a scientific goldmine.

But the researchers aren’t stopping there. The next phase of the project involves analyzing physical fish specimens housed at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, which holds about 3.5 million fish samples from around the world. These preserved specimens allow scientists to extend their timeline even further back and include less-studied native species that aren’t typically targeted by anglers.

By comparing these museum samples with modern fish, researchers can directly examine how body structure and morphology have changed under different climate conditions across decades. This will help them explore new questions—like which environmental factors drive size changes most strongly and whether similar trends are happening in other regions.

How Scientists Determine a Fish’s Age

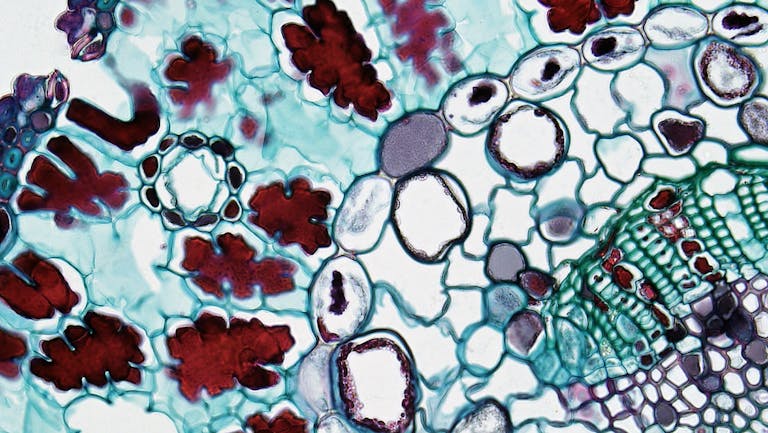

An interesting part of this research lies in how scientists determine fish age. Just like trees, fish scales grow in rings, each representing a period of growth. By counting these rings, researchers can estimate how old a fish is and compare its length to historical norms for the same age class.

This technique allows scientists to detect whether a fish is growing slower than expected for its age, which helps separate the effects of aging from broader environmental trends.

In this study, that method revealed that modern fish of the same age are significantly smaller than their counterparts from the mid-20th century—an unmistakable sign of long-term environmental change.

Global Context: Shrinking Animals and Climate Change

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Michigan. Around the world, scientists have observed that many species are shrinking in response to global warming. As temperatures rise, metabolic rates increase, often leading to smaller body sizes in both aquatic and terrestrial animals.

In lakes and oceans, smaller fish can affect entire food webs, influencing predators like birds, larger fish, and even humans. Body size is a fundamental trait that affects reproduction, survival, and ecological balance.

In Michigan’s case, these shrinking fish serve as a visible warning sign of how climate change is reshaping ecosystems, even in regions that might seem stable and well-monitored.

The Road Ahead

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources continues to collect data from inland lakes, ensuring that researchers like Flood and Alofs can keep tracking these trends. Their work not only monitors fish but also serves as a window into how climate change affects freshwater ecosystems at large.

As the team continues to expand its analysis with museum specimens and additional climate data, the goal is to understand how temperature, oxygen levels, and ice cover interact to drive these biological changes. With climate projections showing continued warming in the Great Lakes region, these findings may represent just the beginning of a much larger shift.

For now, the evidence is clear: Michigan’s fish are shrinking, and it’s yet another reminder that climate change is quietly reshaping nature—even beneath the surface of our lakes.