Wildfire Risk Is Rapidly Reshaping the Economics of Timberland in the Pacific Northwest

Rising wildfire danger across the Pacific Northwest is creating major economic challenges for timberland owners, especially those managing Douglas-fir plantations. A recent analysis from researchers at Oregon State University (OSU) shows that increasing fire risk—combined with the already unpredictable nature of timber prices—may reduce the value of forestland by up to 50%. Even more striking, the study suggests that under the most extreme wildfire scenarios, it becomes financially optimal to harvest Douglas-fir trees at just 24 years old, rather than the 65-year rotation that makes sense when fire risk is not considered.

This shift represents a significant departure from traditional forest management practices. Most private landowners generally harvest Douglas-fir somewhere between those ages, but according to the OSU research team, growing fire exposure changes the entire decision-making landscape. Every additional year a stand remains unharvested increases both its value and its vulnerability, and in a high-fire-risk environment, that vulnerability grows too quickly to ignore.

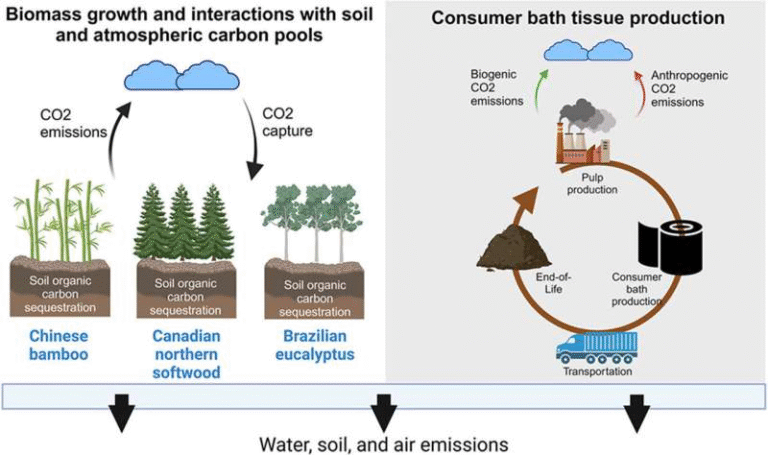

The study—conducted by Mindy Crandall, Andres Susaeta, and doctoral student Hsu Kyaw—appears in Forest Policy and Economics and is among the first to combine wildfire risk, timber price volatility, and carbon sequestration values into a single integrated model that reflects the modern realities of forest management.

Why Wildfire Risk Matters So Much

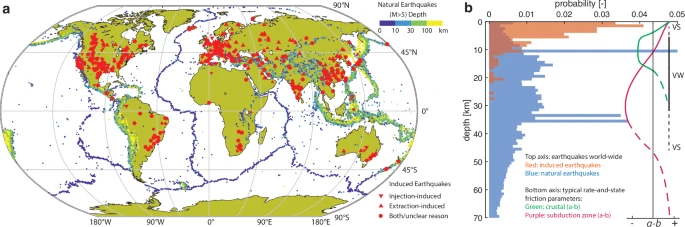

As Douglas-fir stands age, they accumulate more biomass—fuel that can burn intensely during a wildfire. Under extreme conditions, older stands become disproportionately vulnerable. The OSU researchers found that the probability of wildfire increases sharply with stand age, meaning the financial risk of delaying harvest rises every year.

In simple terms, the economic logic is shifting. While older trees are more valuable, the odds of losing them entirely to a wildfire diminish the benefit of waiting. The researchers note that under high-risk scenarios, landowners are effectively “rolling the dice” each year they delay harvest. This dynamic becomes even more pronounced when timber markets experience strong price swings, something the industry is very familiar with.

How Timber Price Volatility Compounds the Problem

The timber market is known for its instability. Prices can shift dramatically based on housing demand, trade dynamics, mill capacity, and global economic cycles. Traditional forest valuation models often assume relatively stable timber prices, which is unrealistic in today’s environment.

The OSU study shows that when volatile timber prices are layered onto increasing wildfire risk, the economics of forestland change significantly. Both factors introduce uncertainty, and when combined, they lower expected returns from long-term rotations and reduce the present-day value of timberland.

This is particularly important in Oregon, where forests cover nearly half of the state’s 96,000 square miles. The Douglas-fir species alone accounts for about 65% of Oregon’s timber stock, forming the backbone of an industry valued at $18 billion annually. These forests also deliver significant ecological benefits, including wildlife habitat and carbon storage—services that are harder to maintain when trees must be harvested earlier.

Carbon Pricing Helps, But Only to a Point

The researchers incorporated carbon sequestration payments into their economic model and found that higher carbon prices generally support longer rotations and higher land values. This makes sense: older trees contain more stored carbon, making them more valuable in a functioning carbon market.

However, these benefits shrink rapidly in situations where wildfire risk is high. A major fire not only destroys timber but also releases stored carbon, erasing both financial and climate benefits. Because carbon credits can be lost to wildfire, landowners may hesitate to rely too heavily on them as a revenue stream unless programs are redesigned to account for fire risk.

The researchers suggest that stronger carbon-offset programs could improve outcomes by including wildfire mitigation credits—for actions such as prescribed burning, thinning, and creating more resilient forest structures—as well as salvage credits that recognize carbon recovery after a fire.

Strategies to Improve Forest Resilience and Economic Stability

To counter the emerging risks, the OSU team identifies several practical strategies that can help landowners maintain both profitability and ecological function:

Fuel Reduction Practices

Methods such as thinning, prescribed burning, and fuel breaks reduce wildfire intensity and allow trees to grow longer before becoming too risky.

Improved Salvage Logging Capacity

Better post-fire recovery operations enable landowners to capture residual value from burned timber, helping stabilize income even after catastrophic events.

Wildfire-Adjusted Insurance Programs

Insurance that accounts for locally rising fire risk could provide a financial buffer for landowners otherwise forced into premature harvest cycles.

Adaptive Zoning

This involves dynamically managing forest zones based on shifting climate, hazard, or economic conditions—rather than relying on static long-term plans.

Cooperative Fuel Management

Since wildfires cross property boundaries, cooperation among neighboring landowners can significantly reduce fire hazards at the landscape scale.

Diversified Forest Composition

Mixed-species, mixed-age forests are more resilient to wildfire, pests, and climate stress, and they offer a wider range of economic opportunities than single-species plantations.

How Shorter Rotations Affect Forest Ecology and Wood Quality

While early harvesting may be financially rational in many scenarios, it comes with drawbacks. Younger trees produce lower-quality timber, which limits the types of products that mills can manufacture. Short rotations also reduce opportunities for wildlife habitat development and diminish long-term carbon storage potential—a key ecosystem service in a warming climate.

From a salvage standpoint, longer rotations offer a higher chance of recovering some financial value after a fire. But even this factor has less influence on landowner behavior than the underlying financial risk associated with holding mature stands in high-risk zones.

Overall, the research makes clear that wildfire risk is not just an environmental issue; it is a major economic force reshaping how forests are managed and valued. The authors conclude that forest policy will need to evolve alongside these changing conditions, blending fire resilience, market adaptation, and carbon strategies to support both environmental and rural economic stability.

Additional Context: Douglas-Fir and Pacific Northwest Fire Trends

The Douglas-fir is one of the most economically important tree species in North America. It grows quickly, produces strong and versatile wood, and is commonly used in construction, plywood, and engineered timber products. Historically, Douglas-fir ecosystems experienced periodic low- to moderate-intensity fires, which helped shape forest structure and species diversity.

Over the last century, however, widespread fire suppression has allowed fuels to accumulate. Combined with hotter, drier summers, this has resulted in larger, more destructive wildfires. In the last decade, the Pacific Northwest has seen multiple standout fire seasons marked by record-breaking burned acreage.

For landowners, this new reality requires balancing economic goals, forest health, and climate resilience—a complex challenge that studies like this help illuminate.

Research Paper

Optimal forest management of Douglas-fir in Western Oregon: Stochastic prices, carbon sequestration and wildfire risk

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2025.103629