Why New Research Suggests Cosmic Dust Might Be Far More Porous Than We Ever Thought

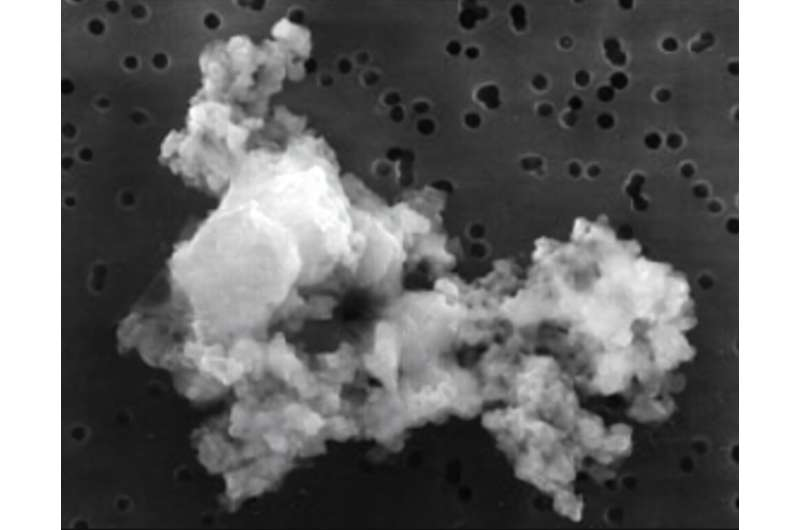

Cosmic dust has always seemed like one of those quiet background characters of the universe—floating around in clouds, forming mesmerizing shapes like the famous Pillars of Creation, and silently contributing to the birth of stars and planets. But a new scientific review suggests we might have been underestimating just how unusual this dust really is. According to recent work led by Alexey Potapov from Friedrich Schiller University Jena, the tiny grains that make up much of the universe could be far more porous, fluffier, and spongier than classic models assumed.

This isn’t just a fun detail. The porosity of dust affects everything from how molecules form in interstellar clouds to how water and other fragile chemicals survive long journeys across space. In this article, we’ll dig into the new findings, what they mean for astrochemistry and planet formation, and why scientists are taking dust more seriously than ever.

What Exactly Is Cosmic Dust?

Before diving into the new findings, it’s useful to understand what cosmic dust actually is. The term “dust” may sound simple, but these particles are not like the house dust we’re used to. Cosmic dust grains are tiny—often smaller than a micron—and made of materials like silicates, carbon, metals, and ices. They float in interstellar clouds, surround young stars in disks, and drift in comets forming the glowing comas we observe from Earth.

Dust grains serve as foundational building blocks in space. They help cool gas clouds, act as seeds for planet formation, and even provide surfaces where important chemical reactions happen. When we think about how planets gain water, how organic molecules form, or how stars grow, cosmic dust quietly plays a role in all of it.

The Big Question: How Porous Is Space Dust?

Scientists have debated the porosity of cosmic dust for decades. Traditional models pictured dust grains as compact, like tiny solid rocks. But the new research argues that many cosmic dust grains may instead be extremely porous, resembling fluffy, sponge-like aggregates with lots of internal empty space.

The paper distinguishes between two types:

- Intrinsic porosity, meaning the grain itself has internal holes—like a hollow carbon structure or a particle with built-in micropores.

- Extrinsic porosity, which comes from grains sticking together loosely, leaving spaces between individual particles.

Understanding how porous dust is matters because porosity changes how dust interacts with light, heat, gas, and chemistry in space.

Four Lines of Evidence Supporting Porous Dust

The authors looked at four major sources of evidence that all point toward high porosity:

1. Spacecraft Dust Samples

Missions like Stardust and Rosetta provided direct physical samples of cometary dust.

- Stardust collected particles from Comet Wild 2.

- Rosetta studied dust around Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Both missions found dust grains ranging from compact to incredibly porous, with some samples reaching up to 99% porosity. That means the majority of the grain’s volume was empty space—almost like a cosmic dust bunny.

2. Remote Observations

Astronomers also study dust indirectly through how it scatters, absorbs, and polarizes light.

- Observations of the HL Tau system using ALMA suggested porosities around 90%, although collisions may compact grains over time.

- A separate study of the IM Lup system showed scattering patterns best explained by fractal aggregates—a mathematical term for highly porous, irregular structures.

These observations align with a universe where dust is fluffier than expected.

3. Laboratory Experiments

Scientists have even tried creating space dust analogues on Earth. Techniques such as laser ablation of rocks produce gas and dust that then settle into aggregates. Interestingly, these lab-grown grains are always extremely porous, matching properties seen in Rosetta’s samples. This suggests porous grains naturally assemble under cosmic conditions.

4. Simulations

Computer models—from large-scale grain collisions down to atom-level structures—show similar trends.

- Hit-and-stick models of early dust growth naturally produce aggregates with high extrinsic porosity.

- Atomistic simulations show micropores can trap water molecules or other volatile substances, protecting them from sublimating in harsh space environments.

This means porous grains may act as tiny delivery vehicles for chemicals essential to forming planets and potentially life.

Why Porous Dust Matters for Chemistry in Space

Porous dust has significantly more surface area than compact dust. This affects space chemistry in major ways:

- Increased surface means more places where molecules like H₂ can form.

- Voids inside dust grains can trap volatiles, shielding them from radiation or heat.

- Dust grains drifting through space might transport water and organic molecules to young planets.

This could reshape how scientists think about the early Earth receiving water or how chemical complexity builds in the universe.

How Porosity Influences Planet Formation

Planet formation begins when dust grains collide and stick together to form larger particles. With porous grains:

- The “hit-and-stick” behavior becomes easier, promoting early growth.

- Higher porosity changes how grains move and settle in protoplanetary disks.

- Experimental and simulation data suggest porous dust remains fragile but can still clump into planetesimals under the right conditions.

This means porous dust may speed up the earliest phases of planet formation.

Open Questions and Scientific Caution

Despite the strong evidence, the authors emphasize that there isn’t yet enough data to prove that most cosmic dust is porous everywhere in the universe. Several challenges remain:

- Some astronomical observations require less porous grains to match thermal or optical data.

- Dust porosity likely varies by environment—comets may hold fluffier grains than dense interstellar clouds.

- Dust can become compacted over time by collisions, radiation, or shocks.

More observations, particularly with advanced telescopes, will help clarify which regions contain porous dust and how common these fluffy grains really are.

Additional Background: How Dust Shapes the Universe

To give more context, here are some additional aspects of cosmic dust worth knowing.

Dust and Star Formation

Dust shields gas in star-forming regions, allowing it to cool and collapse into stars. Without dust, many star-forming clouds would remain too warm to condense.

Dust and Observational Astronomy

Dust absorbs and scatters light, which is why some regions look dark even though they contain stars behind them. Understanding dust texture—whether compact or porous—helps astronomers interpret what they see.

Dust as Carriers of Life’s Ingredients

Dust grains accumulate ice mantles containing water, methanol, ammonia, carbon dioxide, and other molecules. Inside porous grains, these chemicals may be preserved longer, increasing the chances they survive the trip into forming planets.

Dust in Our Solar System

Porous dust isn’t just a distant cosmic phenomenon. Interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) found in Earth’s stratosphere often show fluffy, fragile structures. These grains are likely remnants of comets and may mirror the behavior of dust across the galaxy.

Final Thoughts

This new research gives us a richer, more surprising picture of the universe’s smallest building blocks. Instead of imagining cosmic dust as tiny pebbles, we may need to picture them more like microscopic sponges—fragile, lightweight, and full of empty space. Whether floating between stars or clumping into planets, these grains shape the universe in subtle but profound ways.

As more observations roll in and technology improves, we’ll learn whether fluffy dust is the exception or the norm across cosmic environments. Either way, the universe appears to be a lot spongier than we once believed.

Research Reference:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00159-025-00164-5