Why Habitable-Zone Planets Around Red Dwarfs Probably Don’t Keep Their Exomoons

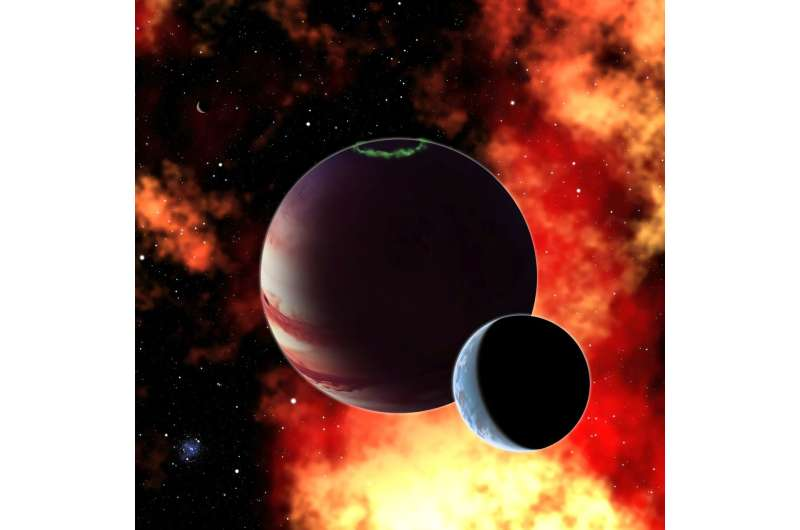

Astronomers have spent decades searching for exomoons—moons orbiting planets in other solar systems—but so far, none have been conclusively confirmed. A handful of candidates exist, yet nothing has cleared the bar for certainty. Still, moons are incredibly common in our own solar system, so it would be strange if they didn’t exist elsewhere. Among all of them, Earth’s Moon stands out. It’s unusually large compared to its host planet, and it’s been a quiet but powerful architect of Earth’s long-term habitability. It stabilizes our axial tilt, shapes our seasons, and drives the ocean tides that support rich coastal biodiversity.

So a natural question arises: Do rocky planets in other star systems—especially those in the habitable zone (HZ)—have moons of their own? And if they do, could those moons influence habitability the way ours does?

A new study titled “Tidally Torn: Why the Most Common Stars May Lack Large, Habitable-Zone Moons” tackles this question with detailed N-body simulations. Led by Shaan Patel of the University of Texas at Arlington, the research investigates whether Earth-sized planets orbiting M-dwarf stars (also known as red dwarfs) can hang on to large moons over long periods of time. The study is set to appear in The Astronomical Journal and is available on the arXiv preprint server.

Why Focus on M-Dwarfs?

M-dwarfs are the most common stars in the Milky Way, making up the majority of stars in our galaxy. They’re cooler and fainter than the Sun, which means their habitable zones lie much closer in. This closeness has major consequences: planets in those inner zones are often tidally locked, with one face permanently turned toward the star. That proximity also shrinks the size of a planet’s Hill sphere, the region where its gravity dominates and can hold onto a moon.

This is where things get interesting—and problematic for exomoons.

What the Researchers Did

The team performed extensive numerical simulations, varying factors like:

- Planet mass

- Semi-major axis (distance from the star)

- Moon size

- Stellar classification (M0 through M9)

They modeled gravitational interactions between the star, planet, and moon, incorporating tidal effects that slowly alter orbits and rotations. Their main goal was to determine how long a large, Luna-like moon can remain stable around an Earth-like planet inside an M-dwarf’s habitable zone.

What They Found

The results strongly suggest that large exomoons around HZ planets in M-dwarf systems are extremely fragile.

The biggest takeaway:

Most Earth-like planets in these systems would lose their large moons within the first billion years—often much sooner.

Here are the specifics:

- For planets around M4-dwarfs, moon lifetimes often drop below 10 million years, an incredibly short timeframe compared to geological or biological timescales.

- Around M5–M9 stars, the situation is even worse—the moons are stripped away even faster due to stronger stellar tides and even smaller Hill spheres.

- Even for more massive planets, instability remains a major challenge.

The team also showed how the strength of stellar tides increases dramatically as the habitable zone moves inward for cooler M-dwarfs. As the star’s gravitational influence grows stronger, it disrupts the delicate orbit of any large moon.

Why Moons Escape

The primary mechanism behind moon loss is the shrinking Hill sphere. A moon must orbit well within this sphere to remain gravitationally bound to the planet. If it orbits too close to the edge, stellar tides and three-body interactions slowly nudge it outward until it escapes the planet’s grasp.

The simulations revealed that even initially stable moons gradually drift outward over time due to tidal evolution, eventually crossing the boundary and breaking free. In many cases, the process unfolds in just millions of years.

Any Chance of Survival?

Interestingly, the study does identify a few rare configurations where a large moon might survive for a long time:

- If the planet orbits an M0-dwarf, where the habitable zone sits farther from the star, the stellar tide is weaker.

- If the planet is slightly more massive—around two Earth masses—the gravitational hold on the moon becomes stronger.

Under these specific conditions, a large moon could potentially survive up to 1.35 billion years. That’s still less than Earth’s Moon has lasted, but it’s long enough to allow meaningful planetary evolution. However, these scenarios represent the minority of possible systems.

What About Smaller Moons?

The researchers point out that smaller moons, such as those comparable to Ceres or Phobos, might survive far longer. Their lower mass means weaker tidal interactions, allowing them to remain stable even where larger moons would be lost. The problem is that these mini-moons are incredibly difficult to detect with current technology. They may exist, but they would remain hidden for now.

Why This Matters for Habitability

Large moons aren’t just pretty ornaments—they can influence a planet’s climate, tilt stability, and ocean behavior. If most M-dwarf HZ planets can’t keep them, that means:

- Less axial tilt stabilization, possibly creating chaotic climate variations

- Weaker or absent tides, reducing coastal mixing and nutrient cycling

- Potentially different patterns of long-term planetary evolution

This doesn’t make M-dwarf planets uninhabitable, but it removes one of the factors that has arguably helped Earth maintain long-term stability.

Future Exomoon Searches

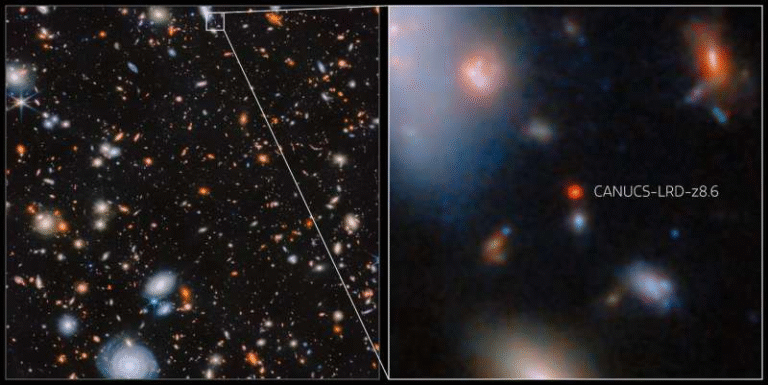

Even if large moons are rare in these systems, astronomers are still actively searching. Instruments currently being used—or planned—include:

- JWST, which is already scheduled to observe potential exomoon signals around the rocky exoplanet TOI-700d

- The proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory, which would use a 6- to 8-meter mirror and could detect moons around some nearby planets

- The Giant Magellan Telescope, expected to begin observations in the 2030s, with a 24.5-meter composite mirror capable of directly imaging some exoplanets and possibly their moons

These tools could help verify whether the trends predicted by this study hold true in real-world systems.

A Quick Look at Red Dwarfs and Their Habitable Zones

Since this study revolves heavily around M-dwarfs, it’s helpful to understand what makes them unique:

- They range from M0 (warmer) to M9 (coolest).

- They often exhibit stellar flares, which can impact planetary atmospheres.

- Their habitable zones sit incredibly close—in some cases only 0.02 to 0.1 AU from the star.

- Tidal locking is common, meaning one side of the planet faces permanent daylight, while the other sinks into everlasting night.

These characteristics shape both the evolution of planets and the possible survival of moons.

What This Means for the Search for Life

Since M-dwarfs make up the bulk of the Milky Way’s stellar population, understanding the environments around them is key for astrobiology. This study suggests that one potential asset for habitability—a large stabilizing moon—may be largely absent from these systems.

That doesn’t rule out life. It simply refines where, and how, astronomers look for it.