Scientists Successfully Turn Dark Excitons Into Bright, Controllable Light States Using Nanoscale Engineering

A team of researchers from the City University of New York and the University of Texas at Austin has achieved something that scientists have been chasing for years: they managed to make dark excitons—light-matter states that normally hide from detection—shine brightly and controllably. This work represents a major leap for nanotechnology, photonics, and quantum science, and it brings us closer to faster, smaller, and more energy-efficient technologies.

Dark excitons are fascinating because, despite their name, they’re not dangerous or mysterious in a sci-fi way. They’re simply pairs of electrons and holes inside atomically thin semiconductors that don’t emit light under normal circumstances. They’re labeled “dark” because their emission is so weak that conventional optical tools can’t see them. Yet these hidden states are incredibly promising: they have long lifetimes, strong quantum stability, and reduced interaction with their surroundings, making them ideal candidates for quantum information systems, on-chip optics, and next-generation sensors.

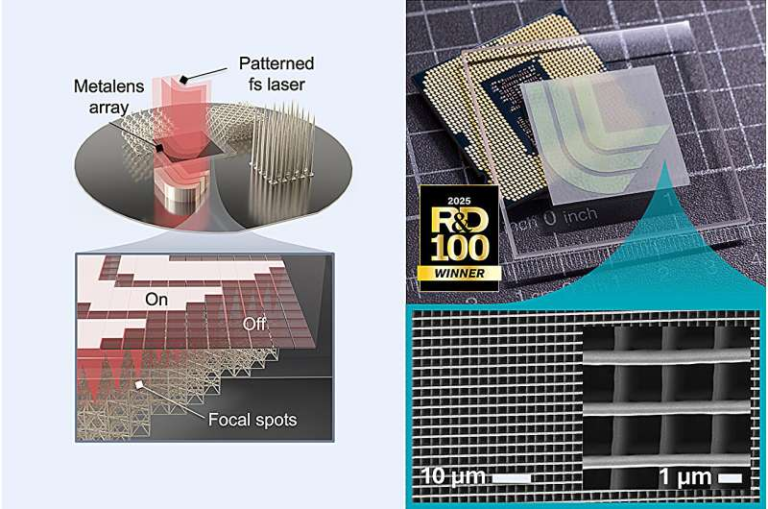

The challenge has always been getting dark excitons to reveal themselves without ruining their natural properties. Most attempts have either failed to brighten them enough or unintentionally altered the underlying material. This new research solves that problem using a precisely engineered plasmonic nanocavity made from gold nanotubes integrated with a single-layer sheet of tungsten diselenide (WSe₂), which is only three atoms thick. This structure concentrates light at incredibly small scales and enhances the emission from dark excitons by about 300,000 times, making them visible and controllable right at their original location.

According to the research team, the core of the solution lies in a careful design that boosts out-of-plane electromagnetic fields, the exact dipole orientation dark excitons respond to. Instead of forcing the material to behave differently, the design enhances what’s already there. Thin layers of boron nitride act as protective spacers so the gold cavities don’t interfere with or charge the semiconductor. This allowed the team to preserve the material’s natural behavior while unlocking multiple new dark exciton states that no one had observed before.

Using this approach, the researchers detected a whole family of previously hidden spin-forbidden dark excitons, each appearing as distinct emission peaks when studied at low temperatures. They also found that by applying electric and magnetic fields, they could switch these exciton states on and off, fine-tune their brightness, and control their behavior with nanoscale precision. That level of tunability is important for any future device that might use these particles for communication or computation.

The implications go far beyond the novelty of making something invisible suddenly bright. This experiment answers a long-standing debate in the nanophotonics community. Many scientists suspected that plasmonic structures, especially metallic ones, would disrupt dark excitons if placed too close to 2D materials. Strong interactions between metals and semiconductors typically cause unwanted doping or destroy delicate quantum states. But by using carefully measured nanoscale gaps and insulating hBN layers, the researchers demonstrated that it’s fully possible to enhance dark excitons without altering what makes them valuable in the first place.

This breakthrough puts dark excitons on the map as practical building blocks for future technologies. Their long lifetimes and inherent stability make them excellent candidates for quantum information processing, where maintaining coherence is crucial. Their ability to be activated and modulated at specific locations means they could work inside on-chip photonic circuits, serving as ultra-low-power optical switches, modulators, or even elements in quantum communication systems. Because this method relies on 2D materials, which are already popular in nanodevice research, the work could translate well into integrated systems.

To better understand the significance, it helps to have a general idea of how excitons work. When a semiconductor absorbs light, an electron jumps to a higher energy level, leaving behind a positively charged hole. The electron and hole can bind together through electrostatic attraction, forming an exciton. In typical 2D materials, some excitons emit light readily—these are bright excitons. Others, because of the way their spins or momenta are arranged, cannot emit photons efficiently. These are the dark excitons. They tend to live longer and interact less with things around them, which makes them especially interesting for quantum applications. But the lack of emitted light makes them extremely difficult to study and control.

The research team solved this by using the unique properties of plasmonic nanocavities, tiny metal structures that trap and intensify electromagnetic fields. When the WSe₂ layer sits inside the gap of a gold nanocavity, the cavity amplifies the weak light associated with dark excitons and channels it outward. The enhancement factor—around 3 × 10⁵—is among the highest ever reported for any light-matter interaction in 2D materials. This level of enhancement made it possible not only to detect dark excitons clearly but also to identify multiple varieties and measure their individual characteristics.

One fascinating part of the study is the discovery of entirely new dark exciton species. The researchers observed a series of emission peaks that correspond to different spin-forbidden configurations, something no prior experiment had revealed. They also found charged dark excitons, sometimes called dark trions, which appear when an exciton binds with an additional electron or hole. Since charged states behave differently under magnetic and electric fields, this adds another layer of control and complexity for potential devices.

The ability to tune dark excitons using external fields is equally important. By adjusting the Fermi level, the researchers could activate or suppress dark exciton and dark trion emission. With magnetic fields, they could reveal how these states split or shift depending on the field direction, confirming their quantum mechanical nature. This tunability means that devices using dark excitons could be actively controlled like electronic or optical components.

Of course, this work is still at the experimental stage. The current demonstrations rely on cryogenic temperatures, which help maintain clean, stable exciton behavior. For real-world applications, systems that operate at room temperature would be ideal, and that remains a challenge. Additionally, while nanocavities can be fabricated with modern lithography techniques, scaling them up for industry is not trivial. The structures need precise spacing, high-quality gold surfaces, and defect-free materials to work properly.

Still, the progress here is undeniable. For years, dark excitons were considered theoretical curiosities or laboratory anomalies. Now, they’re becoming accessible tools. With more research, they may help build compact, fast, and energy-efficient photonic systems. They could contribute to quantum communication networks, where information is encoded in quantum states instead of electrical signals. Their long lifetimes could allow data to be stored or transferred with less energy loss. And because the entire system uses 2D materials, it could integrate well with flexible electronics or next-generation chip architectures.

What makes this breakthrough especially exciting is its simplicity from a conceptual standpoint. Instead of forcing dark excitons to behave differently, the researchers created an environment that complements their natural properties. They matched the cavity’s field orientation to the exciton’s dipole alignment, protected the semiconductor with insulating layers, and designed the structure so carefully that the enhancement emerged without side effects. It’s a reminder that sometimes the best scientific progress comes from working with nature rather than against it.

As scientists continue exploring 2D materials like WSe₂, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), and others, more hidden quantum states may be waiting to be unlocked. Each new discovery adds another building block to the future of quantum photonics and nanoscale devices. This achievement marks a significant milestone on that path and shows what’s possible when precise engineering meets deep understanding of quantum materials.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41566-025-01788-w