Physicists Observe Classical Fluid Instabilities Inside Colliding Quantum Superfluids

Researchers have demonstrated that two colliding quantum superfluids can generate the same kinds of patterns seen in everyday fluid mixing, including mushroom-cloud structures, ripples, and turbulent flows. The work was carried out by a team led by JQI researchers Ian Spielman and Gretchen Campbell, with graduate student Yanda Geng as the lead author. Their findings show how quantum fluids, despite behaving according to the rules of quantum mechanics, can still recreate behaviors traditionally associated with classical liquids such as water or air.

This study focuses on Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs)—a special state of matter produced when atoms are cooled so drastically that they merge into a single, coordinated quantum state. In this experiment, the researchers used BECs made of ultra-cold sodium atoms. Sodium atoms have a quantum property called spin, which makes them act like tiny magnets that can point either along or against an applied magnetic field. By hitting the cloud of atoms with microwaves, the researchers created two different superfluids at the same time: one made of atoms with spin pointing in one direction, and one with spins aligned in the opposite direction.

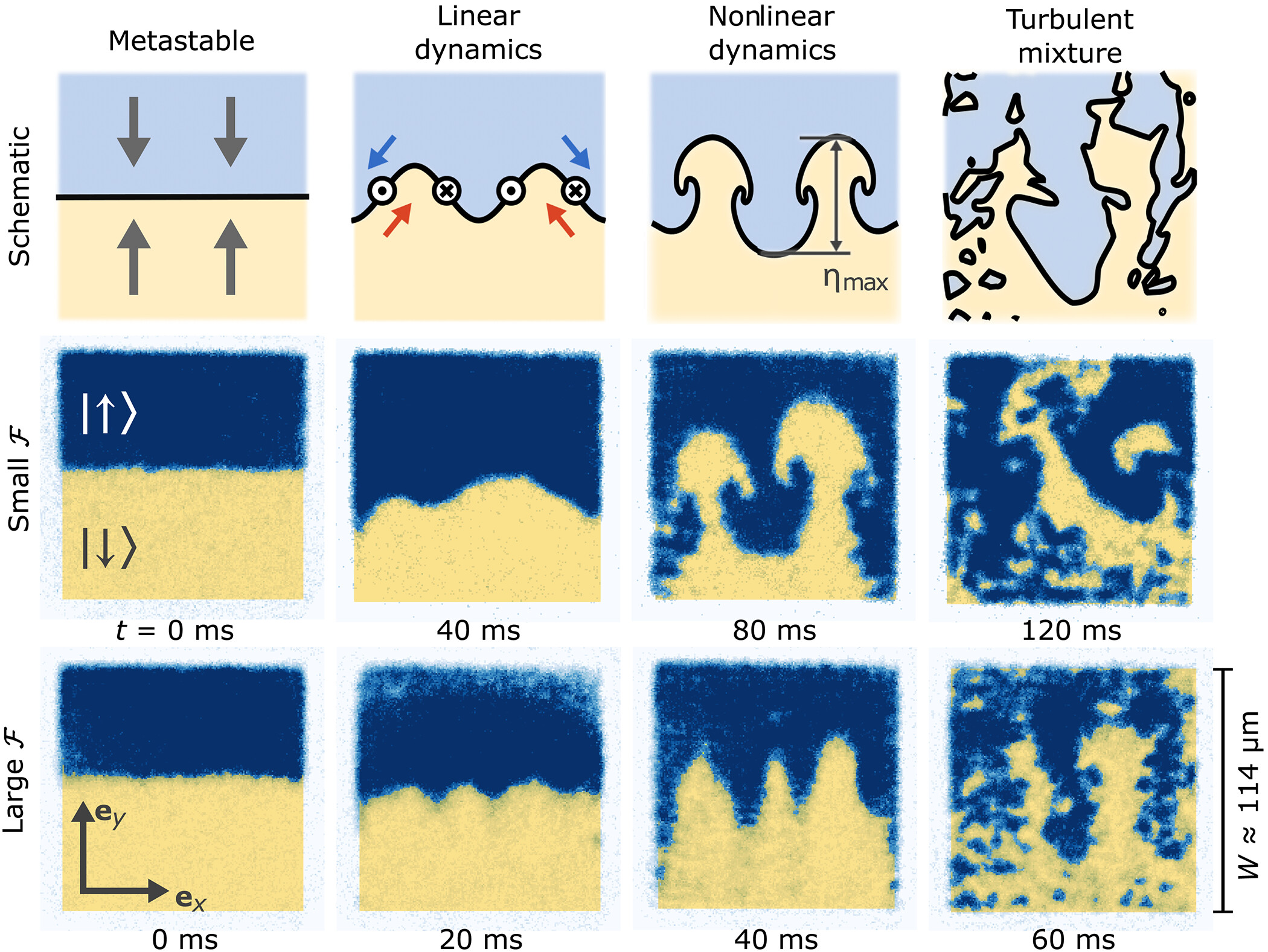

Because these two spin states interact differently with magnetic fields, the BEC naturally separates into two adjacent superfluid layers under an uneven magnetic field. One layer behaves like a heavier fluid, and the other like a lighter one. This setup allows the team to create smooth, controlled interfaces between the two superfluids—interfaces that can then be manipulated to study how instabilities and mixing begin.

The inspiration for the experiment arose by accident. While Geng was troubleshooting magnetic field uniformity in a different project, he repeatedly produced and imaged the two-component BEC. These test images caught the attention of postdoctoral researcher Mingshu Zhao, who noticed swirling features that resembled turbulence in classical fluids. Although the early snapshots were not clear enough to show the iconic mushroom-cloud shapes, they showed hints of interesting behavior where the two superfluids met. After discussions within the team, Geng shifted focus and began exploring whether these mixing patterns were genuine fluid-like instabilities.

To intentionally trigger the effect, Geng and postdoctoral researcher Junheng Tao set up the experiment to place the two superfluids in a stable arrangement, with one lying neatly on top of the other—similar to oil resting on water. They then reversed the direction of the magnetic field gradient. This sudden reversal acted like flipping gravity upside down: the fluid that previously behaved as the “lighter” one was now forced downward, while the “heavier” one pushed upward. This is the exact condition that produces Rayleigh–Taylor instability in classical fluids.

The Rayleigh–Taylor instability occurs whenever a denser fluid sits above a lighter one while a force pulls them in opposite directions. In the natural world, this happens in situations such as water above oil, hot air rising beneath cold air after an explosion, and even in supernovae when layers of stellar material blast outward. Under these conditions, tiny imperfections at the interface grow into large finger-like or mushroom-shaped structures that eventually break apart into turbulence.

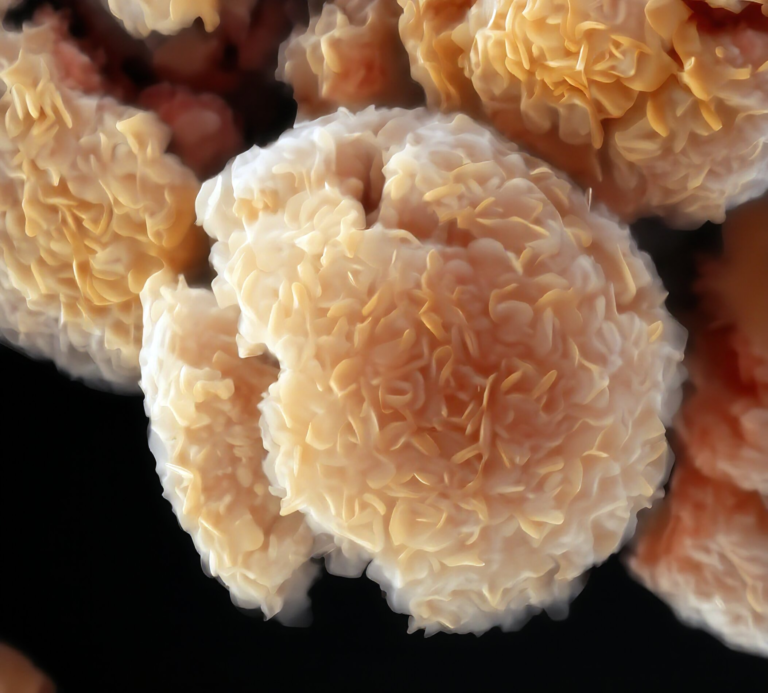

By taking one snapshot for each experimental run—because the imaging process destroys the delicate BEC—the team reconstructed the full evolution of the instability. The images showed the unmistakable mushroom-shaped plumes forming at the interface, just like in classical Rayleigh–Taylor systems, before degenerating into chaotic mixing. The fact that superfluids, which obey quantum laws and flow with no friction, nonetheless reproduced this familiar classical pattern was one of the most striking results of the study.

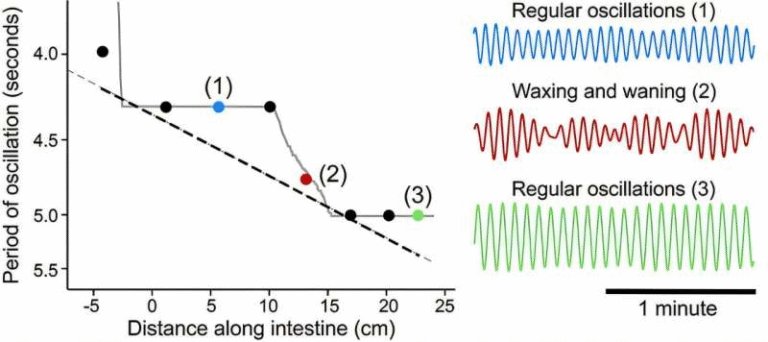

But the experiment did more than show classical-like behavior. Using the unique quantum properties of BECs, the team was able to probe signatures that have no classical equivalent. For instance, they explored the ripples that can form along the stable interface between the two superfluids when the magnetic gradient is varied rhythmically rather than flipped abruptly. These ripples—called ripplons—behave like quantized wave modes because all atoms in each superfluid share a single collective quantum state. The team confirmed that the ripplon behavior follows a dispersion relation similar to surface waves in ordinary fluids, but with noticeable quantum modifications.

A key quantum feature emerges in the form of phase. The phase of a BEC is a wave-like property linked directly to the velocity of the superfluid. Unlike density, phase is normally hidden from direct observation. However, when two BECs overlap, their phases interfere, producing patterns that reveal information about their flow. In this experiment, the interference remained hidden at first, but Geng used a clever technique: by applying a microwave pulse, he transferred the atoms into new internal states where the interference becomes visible in the final image. This allowed the team to measure the velocity of currents flowing along the interface, something typically difficult to achieve with superfluids.

The interference patterns also revealed the emergence of vortices—tiny whirlpools of rotational flow that are quantized in superfluids. These vortices lined up along the interface as the instability progressed, offering deeper insight into how turbulence develops in quantum fluids. In classical fluids, turbulence arises from friction and chaotic eddies. In quantum fluids, turbulence forms through ordered networks of vortices, each carrying a fixed amount of circulation. Capturing these patterns in a controlled experiment provides valuable data for understanding quantum turbulence, a topic of high interest in condensed matter physics and astrophysics.

Interestingly, the experiment also meaningfully substituted magnetism for gravity. In classical Rayleigh–Taylor systems, gravity is the force driving instability. Superfluids in a BEC are far too light and too small for gravity to have a detectable effect. Instead, the team used the magnetic gradient to create a force that mimics gravitational pull. This gave them a unique advantage: by simply adjusting or flipping the magnetic field, they could instantly control the direction and magnitude of the effective force. Classical experiments cannot flip gravity, but this system effectively can.

The study demonstrates how fluid dynamics observed across everyday and cosmic scales can also appear in quantum matter, where they intertwine with phase interference, quantized vortices, and other uniquely quantum features. It highlights how universal certain fluid behaviors are, even when the fluids involved follow entirely different physical rules.

To give additional context, Bose–Einstein condensates have long been used as a platform for studying quantum versions of classical phenomena. They can host vortices, sound waves, solitons, and turbulence-like states. Studying instabilities in BECs allows physicists to test mathematical models that apply both to superfluids and to high-energy astrophysical systems, without needing enormous laboratories or extreme environments.

This new work expands that bridge between the classical and quantum worlds. It shows that the same instability shaping mushroom clouds above explosions and mixing layers in stars can also emerge inside a tiny cloud of ultracold atoms, only millionths of a meter across, controlled by magnetic fields in a laboratory.

Research Paper:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adw9752