New Strain-Engineered Lead-Free Ferroelectric Material Shows Major Breakthrough for Future Electronics

Researchers have discovered a promising way to boost the performance of lead-free ferroelectric materials using mechanical strain instead of chemical modification. This finding could reshape the future of sensors, actuators, memory devices, and even implantable electronics by reducing our dependence on toxic lead-based materials that currently dominate the field.

A team led by physicists from the University of Arkansas, North Carolina State University, and several major U.S. research institutions has demonstrated that the common lead-free material sodium niobate (NaNbO3) can be transformed into a high-performance ferroelectric simply by growing it as a thin film under strain. The work was published in Nature Communications and is already being described as a major advancement in the search for safer, more environmentally friendly ferroelectric components.

Understanding Why Ferroelectrics Matter

Ferroelectric materials have existed in scientific literature for more than a century. They possess a natural electric polarization that can be switched by an applied electric field—and importantly, that switched state remains stable even after the field is removed. This gives ferroelectrics a combination of properties that makes them vital for modern electronics:

- They are strong dielectrics, allowing high-performance capacitors.

- They are piezoelectric, converting electricity to mechanical motion and vice-versa.

- They respond to external forces, making them essential for ultrasound imaging, sonar, fire sensors, inkjet printer actuators, infrared cameras, and computer memory technologies.

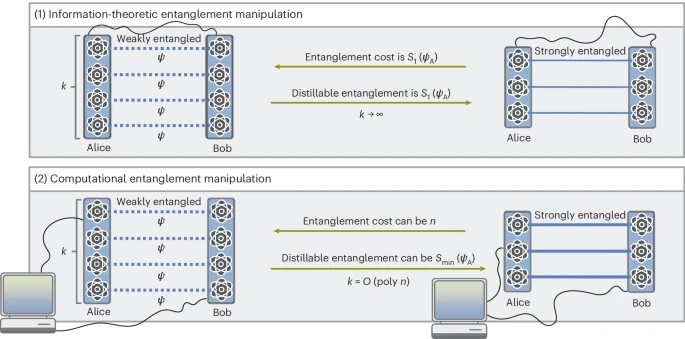

All these abilities become even stronger at what scientists call a morphotropic phase boundary (MPB)—a region where multiple crystalline structures coexist. Lead-based materials such as lead zirconate titanate (PZT) have been champions in this area, delivering unmatched performance. But their downside is significant: they contain large amounts of lead, posing both environmental and health risks.

For many years, researchers around the globe have been working to discover lead-free alternatives that can perform at the same level as PZT without the toxicity. Chemical tuning—mixing different elements to shift a material toward an MPB—has been the main strategy. But this approach fails in many lead-free systems because they contain volatile alkali metals like sodium or potassium that can evaporate during processing.

This is where the new discovery becomes important: instead of altering the chemistry, the researchers altered the structure by applying strain.

What the Research Team Did Differently

The new study focuses on sodium niobate, a flexible lead-free ferroelectric with a complex crystalline structure at room temperature. Scientists already knew that sodium niobate can adopt multiple phases depending on external conditions such as temperature. But changing these phases reliably—especially in thin films—has always been difficult through traditional chemical approaches.

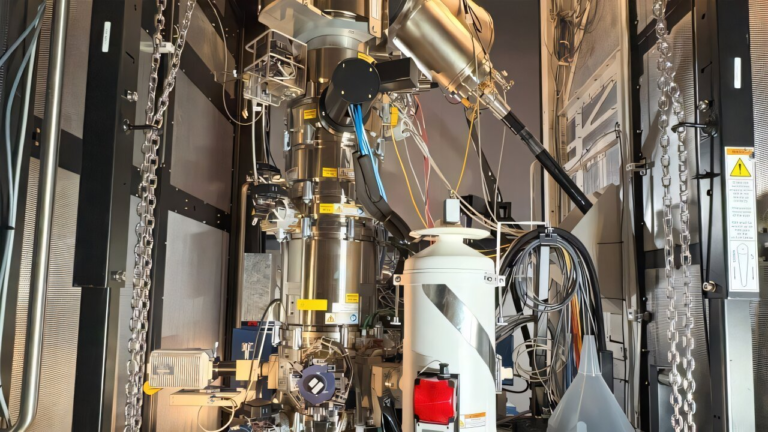

To solve this, the researchers grew an ultra-thin film of sodium niobate on a specially selected substrate. Because the sodium niobate atoms tried to match the pattern of the substrate, the film experienced strain, causing its atomic structure to stretch or compress.

This produced a surprising result: instead of shifting from one phase to another, the strained sodium niobate displayed three different phases at the same time. The presence of multiple phases creates a condition similar to an MPB—the very feature that boosts ferroelectric performance in lead-based materials.

One of the researchers noted that they expected to see a simple transition between phases as strain increased, not a coexistence of three phases. The discovery that sodium niobate naturally formed such a structure under strain was unexpected and scientifically significant.

Experiments were performed at room temperature, and the team now plans to test whether sodium niobate behaves the same way under extreme conditions ranging from minus 270°C to 1,000°C.

Why This Discovery Is Important

The idea of using mechanical strain instead of chemical doping solves many long-standing problems in lead-free ferroelectrics:

• No need for volatile elements to be chemically adjusted

Lead-free ferroelectrics often include metals like sodium or potassium that evaporate easily during chemical processing, ruining the structure. Strain engineering avoids that entirely.

• Thin films become more practical

Many modern devices require thin-film components. Chemical tuning is harder in thin form, but strain tuning works naturally in films grown on substrates.

• More phase boundaries = better performance

The presence of three phases dramatically increases the number of phase boundaries, which are the sites responsible for the strongest ferroelectric and piezoelectric behaviors.

• Potential for biomedical implants

Lead is unsuitable for electronics intended for human implantation. Lead-free, high-performance alternatives could open a new generation of safe implantable sensors, stimulators, and diagnostic chips.

• A scalable, generalizable approach

The same technique could work with other lead-free ferroelectric families, possibly including popular systems like potassium sodium niobate (KNN). This makes the method more than a one-off discovery—it could become a new design rule for next-generation materials.

Additional Background on Sodium Niobate (NaNbO3)

Sodium niobate is part of a broader class of materials called perovskite oxides, which are known for their wide range of electrical and structural behaviors. NaNbO3 is especially interesting because:

- It has a highly flexible lattice.

- It naturally undergoes many phase transitions.

- It exhibits antiferroelectric, ferroelectric, and other structural configurations depending on external conditions.

This flexibility makes it an excellent candidate for strain-engineering experiments.

How Strain Engineering Works in Materials Science

Strain engineering is an approach where scientists deliberately stretch or compress a thin material by growing it on a substrate whose lattice spacing is slightly different. Because atoms prefer to line up in specific ways, the thin film either stretches or squeezes itself to match the underlying surface.

This can create:

- New phases

- Enhanced electrical properties

- Different mechanical responses

- Unusual domain structures

In this case, the strain caused the sodium niobate to form multiple coexisting phases, something rarely observed at room temperature without chemical changes.

Who Was Involved in the Research

The study was a collaborative effort involving scientists from:

- University of Arkansas

- North Carolina State University

- Cornell University

- Drexel University

- Stanford University

- Pennsylvania State University

- Argonne National Laboratory

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The lead author of the paper is Ruijuan Xu of North Carolina State University.

The Road Ahead

The next major step is testing the stability of this strain-induced three-phase structure at extreme temperatures. If sodium niobate retains its behavior under harsh conditions, it could be used in:

- Aerospace sensors

- Energy-harvesting devices

- High-temperature electronics

- Cryogenic instruments

- Long-life actuators and transducers

If the strain-based phase engineering continues to hold up across different materials and environments, it may ultimately replace chemical tuning in many areas of ferroelectric research.

Research Paper:

Strain-induced lead-free morphotropic phase boundary – Nature Communications