Supercomputer Simulation Reveals the Inner Workings of a Quantum Chip With Unprecedented Detail

Researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley have pulled off something that pushes the boundaries of what we can currently simulate on classical hardware. Using the Perlmutter supercomputer at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, the team executed a full-scale, fine-grained simulation of a real quantum microchip. This wasn’t a theoretical abstraction or a simplified model—this was a physically detailed recreation of a chip’s geometry, materials, electromagnetic behavior, and circuit layout. And it required using almost all 7,168 NVIDIA GPUs on Perlmutter for a continuous 24-hour run.

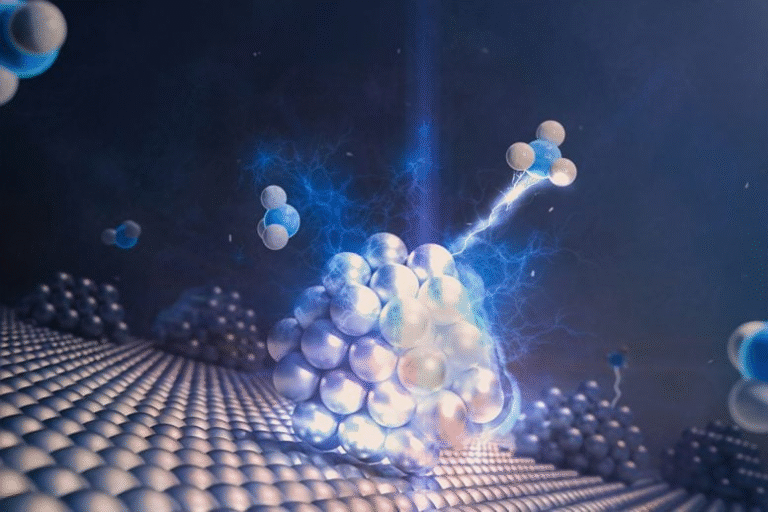

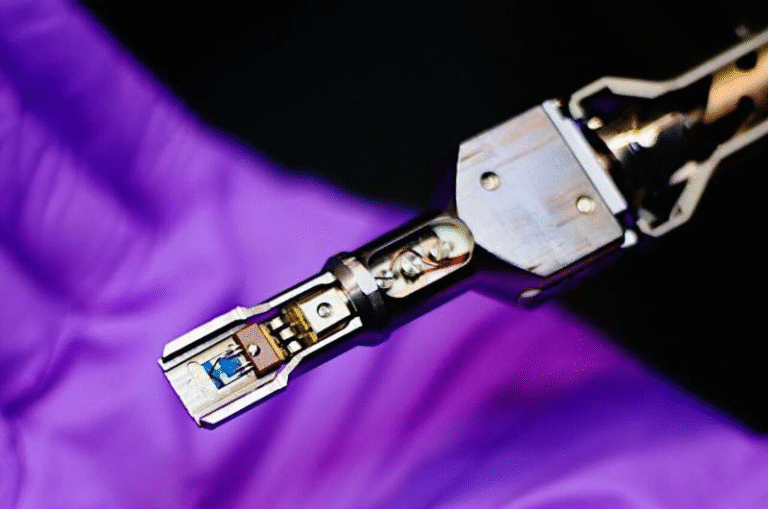

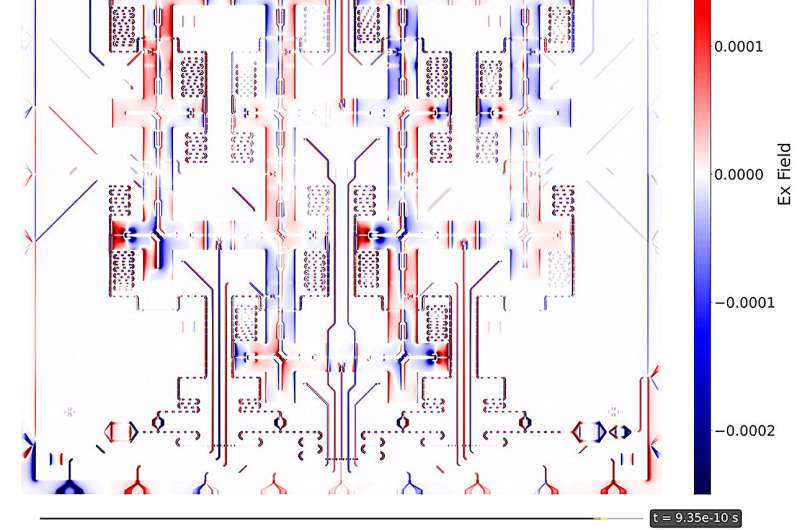

The chip they simulated is tiny—10 millimeters square and 0.3 millimeters thick, with etched features as narrow as one micron. But the engineering complexity inside it is so dense that modeling it required dividing the chip into 11 billion grid cells and solving Maxwell’s equations across more than a million time steps. The result: a simulation that shows, in exquisite detail, how electromagnetic waves actually propagate inside a quantum chip, how qubits and resonators interact, and where unwanted crosstalk might appear.

This is a foundational step toward designing the next generation of quantum hardware. And the key tool behind the breakthrough is ARTEMIS, an exascale electromagnetic modeling framework developed under the U.S. Department of Energy’s Exascale Computing Project.

The Full-Wave Physical Simulation That Sets This Work Apart

Most quantum-chip simulations treat the chip as a black box because fully modeling every metal trace, dielectric interface, resonator geometry, and material choice is computationally overwhelming. Instead, engineers typically rely on simplified frequency-domain approaches or reduced-order models.

What makes this work exceptional is the full-wave, physics-level approach. ARTEMIS solves Maxwell’s equations in the time domain, meaning it captures:

- nonlinear electromagnetic behavior

- transient effects

- reflections and interference patterns

- coupling strengths between different components

- crosstalk caused by geometry and materials

- real-time propagation of microwave signals

The researchers included the exact materials used on the chip, such as niobium metals for wiring and resonator structures, and modeled how these materials interact at tiny scales. Every physical structure—the wiring paths, resonator shapes, and metal interfaces—was part of the simulation.

This level of realism allows the model to show exactly how design decisions affect quantum-chip behavior, something essential for reducing errors, improving qubit coherence, and refining control circuitry.

Using Nearly the Entire Perlmutter System

To complete the simulation within a single day, the team scaled ARTEMIS across nearly the entirety of Perlmutter’s GPU nodes. They executed more than one million simulation time steps in roughly seven hours, all while modeling three separate circuit configurations.

Running on such a massive GPU footprint is extremely rare. According to the researchers, no one has previously performed a physical-level microelectronic simulation at this scale on Perlmutter. It required a combination of:

- 7,000+ GPUs operating simultaneously

- a massively parallel grid representation of the chip

- exascale-oriented computational algorithms

- deep collaboration between modeling experts, chip designers, and HPC engineers

Without Perlmutter’s enormous parallel compute capability, such a detailed simulation would likely take weeks or be impossible to run at full resolution.

Why Modeling Physical Details Matters for Quantum Hardware

Quantum chips—especially those built on superconducting qubits—operate at microwave frequencies. The arrangement of wires, resonators, and control circuitry is incredibly sensitive to physical design. Slight misalignments, parasitic couplings, or unintended resonances can compromise the chip’s performance.

Accurate modeling helps engineers:

- evaluate electromagnetic coupling between qubits

- minimize unwanted crosstalk

- predict signal loss and leakage

- optimize resonator shapes and spacing

- test how different materials affect coherence

- reduce iteration cycles before fabrication

Because fabrication of quantum chips is slow and expensive, having a tool that can reliably predict physical behavior in advance is an enormous advantage.

Until now, researchers had to balance accuracy against computational feasibility. ARTEMIS on Perlmutter removes that compromise.

Experiments Inside the Simulation

One of the most impactful parts of the project is how closely the simulation mimics real laboratory behavior. The time-domain approach lets researchers see how signals actually move across the chip over time, just as they would in a cryogenic test environment.

They can examine:

- how qubits exchange information

- how resonators couple to each other

- how microwave pulses behave as they travel

- how the architecture responds when multiple elements are active

This creates a powerful bridge between theoretical modeling and hands-on experimentation—essential for improving future chip designs.

What the Researchers Plan Next

The team is already preparing the next phase of analysis. Future simulations will focus on extracting quantitative spectral information, specifically how qubits resonate with the rest of the circuit.

They also plan to compare the time-domain results with frequency-domain simulations, creating a cross-validated model that offers higher confidence in both approaches. Once the physical chip is fabricated, they’ll run experiments to compare the real-world behavior with the simulated predictions.

This is the ultimate test: establishing that their detailed, GPU-accelerated model can reliably match actual performance.

The collaboration involved scientists from the Applied Mathematics and Computational Research Division, the Quantum Systems Accelerator (QSA), the Advanced Quantum Testbed (AQT), and NERSC, demonstrating how broad interdisciplinary cooperation can accelerate quantum hardware development.

The Broader Impact on Quantum Computing

This achievement is more than a one-off simulation—it shows how classical supercomputers and quantum-hardware development are becoming deeply intertwined.

As quantum processors continue to scale:

- qubits increase

- wiring density increases

- resonator networks become more complex

- parasitic interactions become harder to predict manually

High-fidelity simulation will become indispensable for engineers designing chips with hundreds or thousands of qubits.

This work also represents one step toward quantum electronic design automation—a quantum-era version of the tools used today to design CPUs, GPUs, and integrated circuits. Just as classical chipmakers rely on systematic modeling workflows, quantum hardware will need its own CAD ecosystem to accelerate innovation.

Simulations like this one show how that ecosystem may develop.

A Quick Primer: Why Quantum Chips Are Hard to Simulate

To add some helpful background for readers, here’s why modeling a quantum chip is so computationally demanding—even before considering quantum effects:

1. Quantum chips operate using microwave signals.

These signals interact with superconducting materials in complex ways, requiring fine electromagnetic modeling.

2. The physical layout matters enormously.

Distances of a few microns can change coupling strengths significantly.

3. The chips are multilayered.

Different layers of metal, dielectric materials, and resonators create interactions across 3D space.

4. Nonlinear behavior occurs frequently.

This is especially true when qubits respond to strong control pulses.

5. Material properties at cryogenic temperatures differ from room-temperature behavior.

These differences must be accounted for to ensure accuracy.

6. Classical computing is still required to design quantum chips.

Even in a future with operational quantum computers, classical HPC systems will remain essential for modeling and validating new hardware.

This simulation demonstrates an important truth: building better quantum computers requires extraordinary classical computing power.

Research Reference:

https://phys.org/news/2025-11-supercomputer-simulates-quantum-chip-unprecedented.html