Harvard and MIT Researchers Demonstrate a Fault-Tolerant Neutral-Atom Quantum Computing Architecture Aiming for Scalable Supercomputers

Quantum computing has long promised a leap far beyond the capabilities of today’s classical supercomputers, but the field has been slowed by one stubborn obstacle: errors. Quantum bits, or qubits, are incredibly fragile and tend to lose their state quickly, threatening any complex calculation. Now, a team led by Harvard University, working closely with MIT and the startup QuEra Computing, has unveiled a system that clears a crucial milestone in this decades-long challenge. Their newly demonstrated neutral-atom platform integrates all the elements required for fault-tolerant quantum computation, bringing a scalable quantum computer closer than ever.

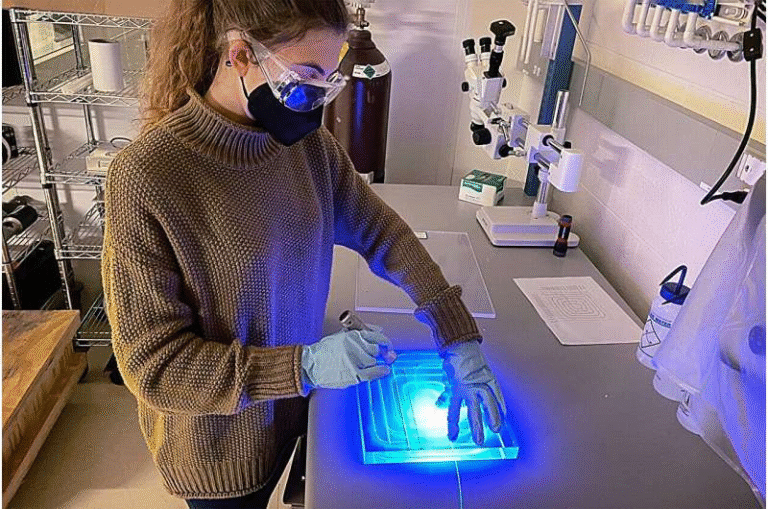

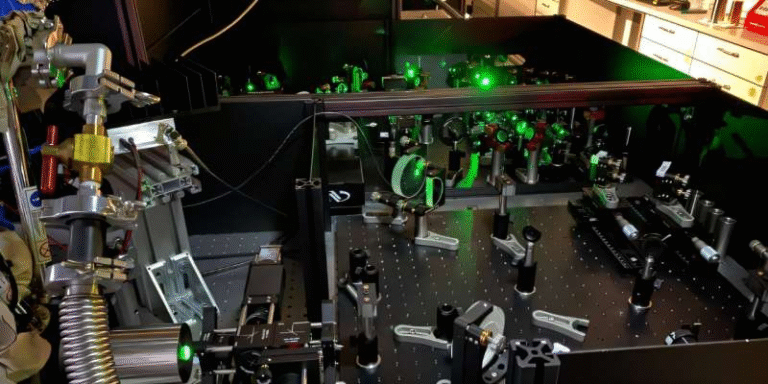

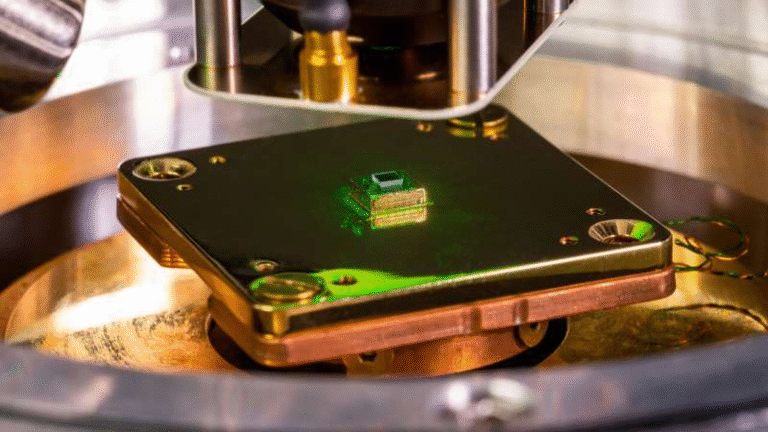

The system described in their recent Nature study uses 448 neutral-atom qubits, all engineered from rubidium atoms arranged and manipulated with optical tweezers. The researchers combined multiple advanced techniques—physical and logical entanglement, logical magic, quantum teleportation, entropy removal, and dozens of layers of quantum error correction—to show that errors can be suppressed below the critical threshold needed for scalability. This threshold is the point at which adding more qubits does not amplify errors but actually helps reduce them through redundancy and correction protocols.

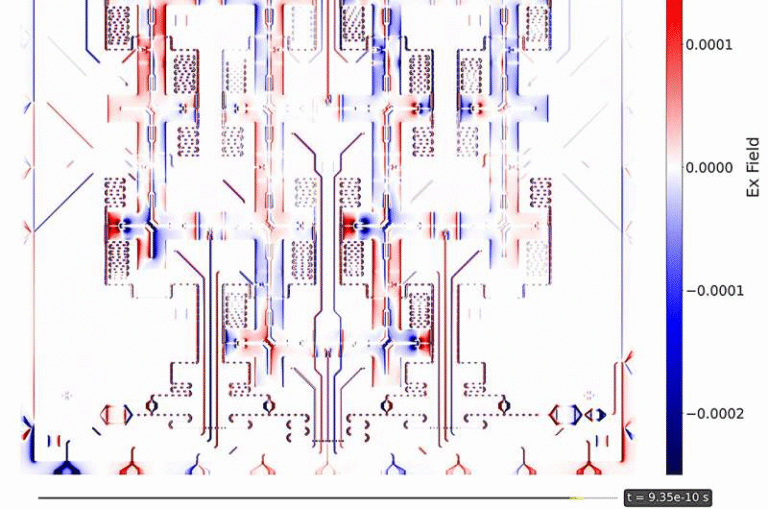

The architecture uses reconfigurable arrays of atoms and supports complex surface-code stabilizer measurements, meaning that qubits can be checked repeatedly for errors while computations continue. These error-suppression rounds achieved performance roughly 2.14× below threshold, a major achievement because no universal, fault-tolerant quantum computing system—on any platform—has previously demonstrated such integrated capabilities at this scale. Physical qubits were combined into logical qubits, and the team performed deep-circuit operations using teleportation-based logic and lattice-surgery techniques. The system even reused qubits mid-circuit after removing entropy, which reduces overhead and helps push the machine closer to practical computation.

This achievement builds on earlier work from the same research groups. In September, the Harvard-MIT-QuEra collaboration demonstrated a separate system with over 3,000 neutral-atom qubits operating steadily for more than two hours, successfully addressing atom-loss issues that previously hindered scaling. Each experiment has been part of a larger push toward identifying which quantum technologies truly offer a viable path to million-qubit machines.

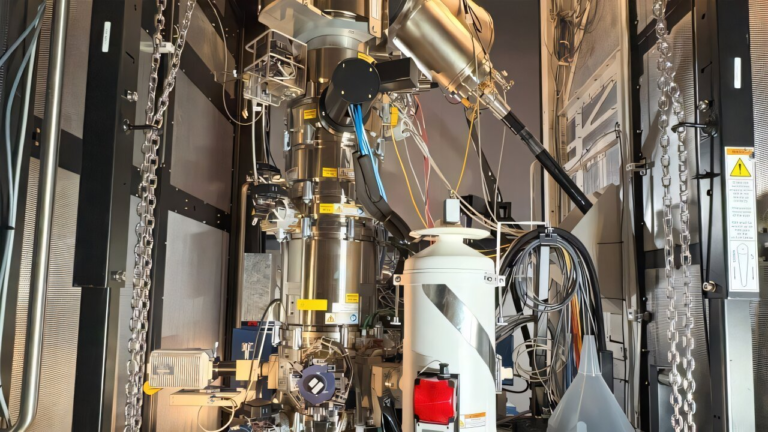

Neutral-atom systems are an increasingly popular hardware approach for several reasons. First, atoms naturally have identical properties, removing fabrication inconsistencies that trouble superconducting chips. Second, neutral atoms can be trapped, moved, rearranged, and entangled using laser arrays, producing highly flexible connectivity patterns. Third, these systems operate at or near room temperature, avoiding the cryogenic cooling requirements of superconducting qubits. This makes them attractive for large-scale architectures where power efficiency and manageability become major issues. Companies such as QuEra are actively developing commercial neutral-atom systems, and leaders in the broader quantum industry, including teams at Google Quantum AI, have acknowledged the rapid progress being made in this platform.

The new results do not signal the end of quantum computing’s challenges, however. The researchers are careful to point out that achieving millions of qubits—along with ultra-low error rates, large numbers of logical qubits, long circuit depths, and integrated magic-state factories—will require significant engineering advances. Even though the threshold has been beaten, useful quantum computing requires extremely reliable logical operations performed at massive scale and maintained over long periods of time. In other words, this experiment demonstrates that scaling is conceptually feasible, not that a full-scale machine is already within reach. Still, the step from theory to a working demonstration is one of the most important milestones in the field’s history.

To better understand why this is so important, it helps to review how error correction works in quantum systems. Classical error correction can simply copy data, but qubits cannot be copied because of the no-cloning theorem. Instead, quantum error correction spreads information across multiple entangled physical qubits. If one qubit suffers a disturbance, the system can detect and fix the issue through stabilizer measurements without destroying the encoded information. Every logical qubit may require dozens or even thousands of physical qubits, depending on noise levels. This is why crossing the error threshold is crucial: below it, encoding becomes more efficient as the system grows.

Another essential part of this architecture is quantum teleportation, which allows the state of one qubit to be transferred to another distant qubit without direct interaction. This is achieved through entanglement and classical communication and plays a key role in enabling fault-tolerant logical gates. Techniques such as lattice surgery help join and split entangled patches of qubits, allowing computation to proceed even within a highly redundant and error-checked framework.

The research also highlights the expanding role of magic states, specialized quantum resources required to implement universal logic gates that cannot be performed transversally in surface codes. These magic states are expensive to create and require distillation protocols, which themselves demand deep circuits and robust error correction. Demonstrating these building blocks in a real system is critical for any future quantum computer that intends to run meaningful algorithms.

The implications of this progress reach across many fields. Quantum computers could one day simulate complex molecules for drug discovery, design new materials, optimize financial systems, enhance artificial intelligence, or solve cryptographic problems beyond classical reach. A quantum system with a few hundred high-fidelity logical qubits could already begin to outperform classical machines in specialized tasks. With millions of logical qubits, entirely new areas of computation could emerge.

Beyond the core experiment, the research reflects an intense worldwide competition among platforms: neutral atoms, trapped ions, superconducting qubits, photonic qubits, and topological qubits are all being actively pursued. Each has different strengths, but the neutral-atom platform’s reconfigurability, scalability, and near-room-temperature operation make it a standout candidate. The fact that this architecture has now demonstrated integrated fault tolerance provides strong evidence that it may become one of the major pillars of next-generation quantum computing.

Although large-scale quantum computers remain years away, the field is accelerating quickly. With each new demonstration—thousands of qubits held for hours, fault-tolerant logical operations, teleportation-based logic, scalable architectures—the vision becomes more concrete. Many researchers who began working in the field decades ago are now seeing the fundamental pieces fall into place. For the first time, the idea of a practical, scalable quantum machine is not just theoretical but grounded in experimental evidence.

As the technology continues to mature, more breakthroughs are expected in error-rate reduction, qubit-control fidelity, laser-stability improvements, modular quantum networking, and automated qubit calibration systems. These developments will play a key role in moving from laboratory demonstrations to fully functional quantum processors capable of tackling real-world problems.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09848-5