Virginia Tech Engineers Develop a High-Voltage Electrostatic Method to Remove Frost Without Heat or Chemicals

Frost may look harmless, but anyone who has scraped ice off a windshield or waited for a heat pump to defrost knows how stubborn and energy-hungry it can be. Traditional defrosting relies on heating elements or chemical agents, both of which come with downsides—high energy use, environmental concerns, and cost. That’s why a new technique developed by researchers at Virginia Tech is attracting attention. They’ve created a method called electrostatic defrosting, or EDF, which uses controlled electric fields to remove frost without melting it or spraying chemicals on it.

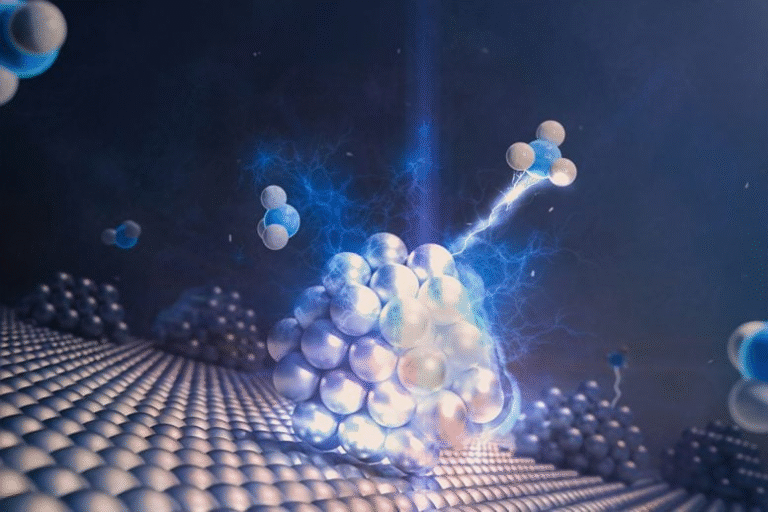

This new approach taps into the natural electrical behavior of ice itself. Ice crystals aren’t perfectly arranged; they contain tiny built-in flaws called ionic defects, where a water molecule might have an extra hydrogen atom (forming H3O+) or be missing one (forming OH–). These imbalances lead to local positive or negative charges scattered throughout the frost. By taking advantage of these natural charges and amplifying them with an external electric field, the researchers found a way to make frost physically jump off surfaces.

Their recently published study in Small Methods details how this works, why it matters, and how close we might be to frost-free winter mornings without scraping or blasting heat.

How Electrostatic Defrosting Works

The foundation of EDF lies in how frost naturally forms. As frost crystals grow, water molecules lock into a structured lattice. But imperfections—those ionic defects—introduce small pockets of positive or negative charge. These defects are normally random and not strong enough to do anything useful.

The Virginia Tech team, led by Jonathan Boreyko, explored whether they could enhance this natural polarization. Their idea was simple: place a conductive electrode above the frosted surface and apply a positive voltage. If the electrode becomes positively charged, the negatively charged defects in the frost should be attracted upward, while the positively charged ones push downward. This polarization creates a pulling force strong enough to detach parts of the frost layer.

Before applying any voltage, the researchers noticed something interesting. When they positioned a copper plate above the frost without powering it, around 15% of the frost detached on its own. This happened because frost can weakly polarize by itself. But once voltage entered the picture, everything became much more dramatic.

With 120 volts, frost removal jumped to 40%. Increasing the voltage to 550 volts removed 50% of the frost. The frost didn’t melt; instead, chunks of it fractured off and shot upward toward the electrode. This is a fundamentally different mechanism from heaters or chemical sprays. The frost literally “leaps” away.

The Unexpected Drop in Performance at High Voltage

The team expected that higher voltages would continue to improve results. But once they pushed beyond 550 volts, something unexpected happened. At around 1,100 volts, frost removal dropped to 30%, and by 5,500 volts, only 20% of the frost detached.

This seemed to contradict the theoretical model they initially used, which predicted that increasing voltage should strengthen the electrostatic attraction and therefore boost removal. The sudden decline forced the researchers to dig deeper.

They eventually found the culprit: charge leakage.

When frost was grown on a copper substrate, the charge from the polarized frost leaked into the metal. This leakage weakened the electrostatic forces, especially at high voltages. The system simply couldn’t build up enough polarization for strong frost removal because the charge kept dissipating into the conductive surface.

To verify this, they repeated the experiment on an insulating glass substrate. The high-voltage performance improved slightly, confirming that reducing conductivity helped maintain polarization.

But the real breakthrough came when they switched to a superhydrophobic surface—something that traps air pockets and is also highly insulating.

Superhydrophobic Surfaces Amplify the Electrostatic Effect

When the frost was grown on a superhydrophobic substrate, the results suddenly matched the original theoretical expectations. With this surface, the researchers saw frost removal increase as voltage increased, reaching up to 75% removal at the highest tested voltage.

Because the surface repels water and traps air beneath the frost, it dramatically reduces charge leakage. The electric field remains strong, the ionic defects polarize more effectively, and the frost detaches more easily.

During one test, the electrostatic removal was so strong that a hidden “VT” logo etched beneath the frost became visible after the ice jumped off. That sort of sudden clearing demonstrates the potential strength of EDF when configured correctly.

Why This Research Matters

If EDF can be refined and adapted to real-world surfaces, it could change how we handle frost and ice in a wide range of industries. Here are a few examples:

Transportation:

Cars, trucks, trains, and planes all suffer from frost buildup. Aircraft wings, in particular, rely on complex and expensive deicing procedures. EDF could become a chemical-free, low-energy solution, especially if surfaces can be engineered to reduce charge leakage.

HVAC and Heat Pumps:

Frost on heat pump coils can reduce efficiency by more than half. A system that rips frost off coils without heating them would preserve efficiency and cut operating costs.

Industrial Refrigeration:

Cold-storage facilities spend large amounts of energy fighting frost accumulation. EDF could lower power use and maintenance needs.

Consumer Applications:

Imagine car windshields, outdoor sensors, solar panels, or even sidewalks that clear frost using electricity instead of heaters or chemicals.

The environmental impact could also be significant. Deicing chemicals can contaminate soil, groundwater, and waterways. EDF eliminates that issue entirely.

Challenges Ahead

Despite its promise, EDF is still in an early experimental stage. Several challenges remain:

- Substrate dependence: It works far better on insulating or superhydrophobic surfaces than on metals. Many real-world surfaces are metallic.

- Incomplete removal: Even the best tests removed 75%, not 100%, of the frost. Full removal is still a research goal.

- High voltage requirements: While the energy use is low, the voltage needed is high. Engineering safe, scalable systems is essential.

- Complex ice conditions: Real frost has varying thicknesses, textures, and moisture levels. EDF must handle all these variations reliably.

Still, the progress is impressive for a first publication. The team plans to explore new electrode arrangements, higher voltages, improved insulating surfaces, and strategies to further minimize leakage. Their long-term aim is achieving complete frost removal—a full 100%.

Understanding the Science of Frost and Ionic Defects

Since EDF relies heavily on the physics of frost, it’s worth briefly exploring what ionic defects are and why they matter.

In a perfect ice crystal, every water molecule bonds neatly with its neighbors. But nature rarely produces perfect crystals. Small structural mistakes occur constantly. When a water molecule has an extra hydrogen, it forms H3O+, a positively charged defect. When it loses a hydrogen, it forms OH–, a negatively charged defect.

These defects can move through the ice lattice, creating pathways for charge transport. In everyday conditions this doesn’t matter much. But under an applied electric field, these defects can shift dramatically, giving ice some surprising electrical properties.

EDF effectively forces these ionic defects to reorganize, causing the frost sheet to polarize like the plates of a capacitor. Once the electric force overcomes the mechanical adhesion between the frost and the surface, the frost snaps off.

This is why charge leakage is such an issue—if the charge can escape into the substrate, polarization collapses.

The Future of Electrostatic Deicing

As the research moves forward, multiple avenues could help EDF become practical:

- Surfaces designed to reduce leakage

- Flexible electrode shapes that conform to real objects

- Lower-voltage systems using optimized materials

- Integration into existing heating and sensing technologies

- Use in hybrid systems where EDF handles frost and another method handles thicker ice layers

The idea of ice jumping off on its own is both visually striking and scientifically elegant. EDF doesn’t melt ice; it mechanically detaches it using its own internal structure. That’s a completely different way of thinking about frost removal—one that could open doors to greener and more efficient winter technologies.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202501143