High-Resolution Airborne Sensors Reveal Major Ammonia Plumes Across California’s Imperial Valley

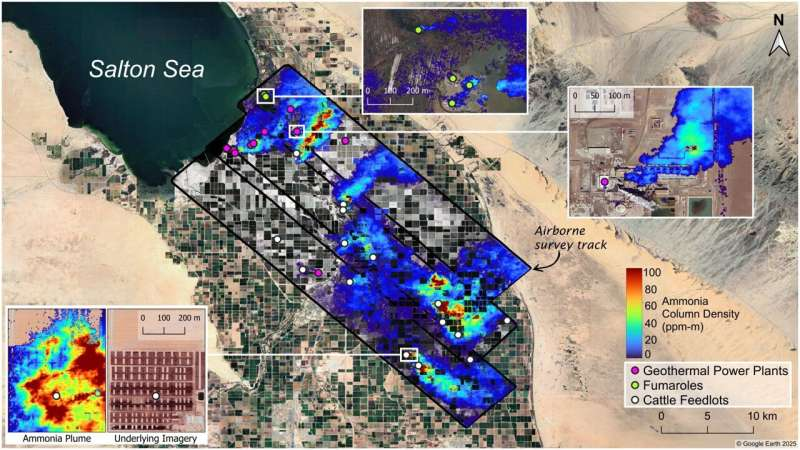

A new research effort led by teams from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and The Aerospace Corporation has produced some of the most detailed maps ever created of ammonia emissions across California’s Imperial Valley and parts of the Eastern Coachella Valley. Using advanced airborne imaging, the scientists traced ammonia plumes back to their exact sources, offering crucial insight into how this gas moves through the environment and how it contributes to harmful PM2.5 pollution.

This study matters because ammonia is a key precursor to the formation of fine particulate matter—specifically particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5). These particles are linked to elevated risks of asthma, heart disease, and respiratory illnesses. Ammonia itself is not highly toxic in low concentrations, but once it reacts with other compounds in the air, it forms tiny solid particles capable of entering the bloodstream.

Below is a clear breakdown of the findings, methods, and broader environmental context—along with additional background to help readers understand why ammonia monitoring is becoming increasingly important.

High-Resolution Mapping of Ammonia Emissions

The research, published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, used data from several flights conducted on March 28 and September 25, 2023, directly over the Imperial Valley and the Eastern Coachella Valley. These flights carried an airborne long-wave infrared imaging spectrometer called Mako, developed by The Aerospace Corporation.

Mako detects infrared light absorbed by ammonia and maps it at extremely high detail—down to 2-meter (6-foot) spatial resolution. This resolution is far sharper than current satellite measurements, which typically only distinguish areas on the scale of tens of kilometers. Because ammonia only remains in the atmosphere for a few hours before reacting with other gases, having this kind of detail is essential for finding its true origins.

Alongside the airborne data, the team collected ground-based measurements from a fixed monitoring station in Mecca operated by the South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD) and a mobile ground spectrometer developed by the University of California, Riverside. These ground readings helped verify and calibrate the airborne results.

Where the Ammonia Is Coming From

The research found several key sources of ammonia in the region:

1. Agricultural Fields and Livestock Feedlots

Large-scale animal operations—especially cattle farms—were identified as major contributors. The largest feedlot observed during the study produced a plume up to 1.7 miles (2.8 km) wide and extending 4.8 miles (7.7 km) downwind during the March flight. This type of emission comes mainly from animal waste.

2. Geothermal Power Plants

The Imperial Valley is rich in geothermal activity, and several power plants in the region were found to be releasing ammonia. These emissions primarily come from cooling towers, which are part of the plants’ normal operations.

3. Natural Geothermal Vents and Fumaroles

On the southeastern edge of the Salton Sea, the team mapped small plumes rising from natural geothermal vents. These vents release superheated water and steam that interact with nitrogen-bearing minerals in the soil, producing ammonia as a byproduct.

4. Other Agricultural Activity

Fields treated with nitrogen-rich fertilizers can emit ammonia, especially under certain temperature and soil conditions.

Overall, ammonia concentrations in parts of the Imperial Valley were found to be 2.5 to 8 times higher than concentrations measured in the Mecca community of the Coachella Valley, which served as a lower-background comparison area.

Why the Imperial Valley Matters

The Imperial Valley is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States. It has:

- Intensive cattle farming

- Fertile agricultural fields

- Numerous geothermal power facilities

- Natural geothermal activity near the Salton Sea

Despite these significant emission sources, ammonia has historically been poorly monitored. There is no comprehensive, continuous monitoring network for ammonia in the region, and previous satellite studies lacked the resolution necessary to identify individual sources.

This new research helps close those gaps by combining high-resolution airborne imaging with strategic ground-level observations.

What the Researchers Learned About Air Quality

Ammonia is a secondary pollutant, meaning it doesn’t cause the largest problems on its own but becomes dangerous after reacting with other compounds. When ammonia meets sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere, it forms ammonium salts—tiny solid particles that qualify as PM2.5.

These particles:

- Can penetrate deep into the lungs

- May enter the bloodstream

- Are associated with asthma, lung cancer, and cardiovascular diseases

Due to stricter regulations on vehicle emissions over the past decades, direct PM2.5 emissions have decreased significantly. This has shifted scientific interest toward secondary sources of particulate pollution—especially ammonia.

The study’s detailed maps show ammonia plumes forming near their sources and then merging into larger clouds as they move downwind. Such information is essential for air-quality agencies that want to understand how pollution spreads across communities.

The data also influenced AQMD’s decision to expand its ammonia monitoring network and continue operating the Mecca station.

Seasonal and Wind-Driven Behavior

The Mecca ground station picked up seasonal variations in ammonia concentrations, suggesting that weather patterns influence how ammonia moves from the Imperial Valley toward the Coachella Valley.

Wind patterns in certain months appear to push emissions northward, giving Coachella Valley residents exposure to pollution that did not originate locally.

This kind of nuanced movement is something satellites cannot capture effectively—but airborne sensors can.

Why Ammonia Is Hard to Monitor

The challenge with ammonia monitoring comes down to chemistry, physics, and technology:

- Ammonia lasts only a few hours in the atmosphere.

- It reacts quickly, making fixed monitoring stations insufficient unless someone already knows the location of the source.

- Satellites often have resolutions of 10–50 km, far too coarse to identify individual sources like feedlots or geothermal vents.

- Most air-quality monitoring focuses on carbon dioxide, ozone, nitrogen oxides, and direct particulate emissions—not ammonia.

This study demonstrates that high-resolution airborne imaging can fill these gaps.

Broader Background: Understanding Ammonia and PM2.5

To give readers more context, here are some important facts about ammonia and particulate pollution:

What Is Ammonia (NH₃)?

Ammonia is a nitrogen-containing gas with a strong smell, produced by:

- Animal waste

- Fertilizer use

- Decomposition of organic matter

- Industrial and geothermal processes

It is highly soluble in water and reacts quickly with acids in the atmosphere.

Why PM2.5 Is Dangerous

PM2.5 refers to particles under 2.5 micrometers in diameter. These particles are linked to:

- Increased respiratory illnesses

- Reduced lung function in children

- Long-term cardiovascular disease

- Premature death in high-pollution areas

The Imperial Valley, Coachella Valley, and surrounding regions already face challenges from vehicle emissions, desert dust, and agricultural activity. Ammonia adds another layer to this complex air-quality puzzle.

What This Study Means for the Future

The results demonstrate that detailed ammonia mapping is possible and valuable. It provides air-quality agencies with a practical way to identify which sources need the most attention. The study also suggests that:

- High-resolution ammonia monitoring could become a tool for environmental regulation.

- More regions could benefit from similar airborne surveys.

- Next-generation satellites might one day achieve this level of precision globally.

- Communities affected by industrial, agricultural, or geothermal activity could get clearer answers about what they’re breathing.

The researchers see ammonia as one piece of a much larger air-quality puzzle—but an increasingly important piece, especially in regions where agriculture and geothermal activity are both prominent.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-25-11935-2025