Machine Learning Helps Create New Ultrafiltration Membranes That Sort Molecules by Chemical Affinity

Cornell University researchers have developed a new type of ultrafiltration membrane that can separate molecules based not just on size but also on their chemical makeup, marking a major shift from how filtration technology has traditionally worked. This breakthrough could change how industries such as pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and chemical manufacturing handle purification tasks that were previously difficult or impossible with standard membrane systems.

For decades, ultrafiltration membranes relied almost exclusively on size-based separation. If two molecules were the same size and weight, standard filters could not distinguish between them. This limitation has been especially challenging in fields like biopharmaceutical production, where two antibodies or proteins might be structurally different but physically similar. The new research from Cornell addresses this exact problem using a clever combination of block copolymer chemistry, self-assembly, and machine learning.

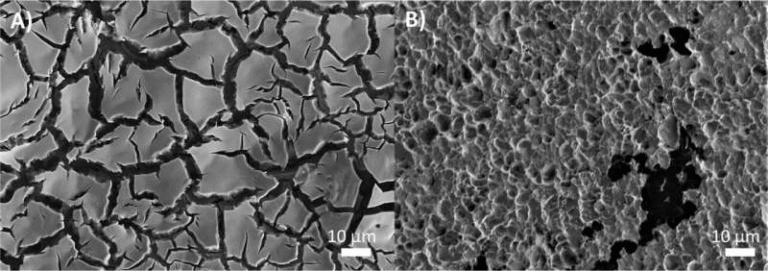

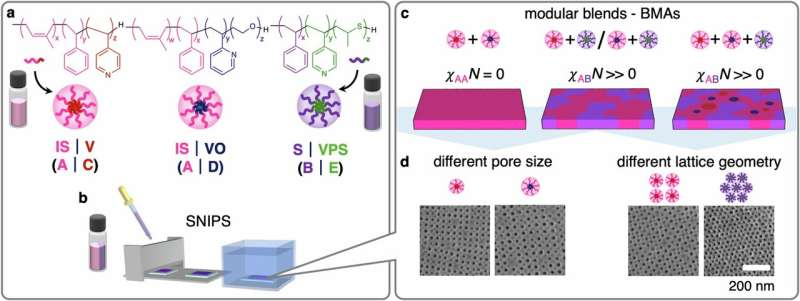

The team created porous membrane films using mixtures of chemically distinct block copolymer micelles. Micelles are tiny self-assembling polymer spheres that, when cast into films, naturally form pores. By blending two or even three types of micelles—each with their own chemical characteristics—the researchers created membranes whose pore surfaces contain different chemical regions. This gives the membrane the ability to interact selectively with molecules based on their chemical affinity, not just their size.

The idea sounds simple, but making it work experimentally involved tackling a number of challenges. The scientists had to understand how neutral and repulsive interactions among different micelles would determine their final positions in the membrane’s top separation layer. Depending on how the micelles compete or cooperate during the assembly process, their chemistries end up arranged differently within the pore surfaces. This detailed mapping of micelle placement is essential because the location of each micelle type determines how the resulting membrane interacts with specific molecules.

Using scanning electron microscopy, the lead researcher captured hundreds of images of the membrane surfaces. However, traditional imaging techniques could not reliably identify which micelle chemistry was appearing in which pore. To solve this problem, the team turned to machine learning. By training a segmentation model capable of detecting subtle variations in pore patterns, they were able to distinguish between different micelle types on the surface. This approach revealed chemical patterns that human observers would likely have missed.

Alongside the imaging work, molecular simulations helped clarify the rules behind micelle self-organization. These simulations required highly coarse-grained models due to the large number of micelles involved and the fact that the system tends to assemble into states far from equilibrium. The simulation work supported the experimental results by showing why certain chemical blends produced specific pore arrangements.

One of the most significant aspects of this new approach is that it integrates chemical specificity into the fabrication process, not as an expensive after-treatment. Traditional attempts to give ultrafiltration membranes chemical selectivity usually involve additional processing steps such as surface functionalization or grafting, which can be costly and impractical at industrial scale. In contrast, the method demonstrated by the Cornell team allows manufacturers to adjust the membrane’s chemistry simply by altering the micelle formulation—the “recipe” that goes into the casting process. This could allow companies to use their existing manufacturing infrastructure with minimal changes.

The research builds on earlier work from the same group, which already led to the creation of Terapore Technologies, a company that produces scalable block-copolymer-based ultrafiltration membranes used for virus separation in biopharmaceutical applications. This new development could extend the usefulness of those manufacturing techniques, enabling the production of membranes that are not only cost-effective but also chemically programmable.

If adopted widely, chemically selective ultrafiltration membranes could have a major impact on industries that require fine molecular separations. Pharmaceutical companies in particular could benefit from the ability to separate proteins, antibodies, or therapeutic molecules that differ in chemistry but not size. This could improve purification efficiency, reduce costs, and expand the range of molecules that can be isolated. Additionally, membranes with tailored pore chemistries could inspire new ideas beyond filtration, such as responsive coatings, chemical-sensing materials, or biosensors capable of binding specific molecules.

The researchers plan to continue studying how deeply these chemical patterns extend into the membrane’s interior. Understanding the distribution of micelle chemistry not just on the surface but throughout the separation layer will be critical for designing membranes with predictable and reliable performance. Future work may also explore how different chemical blends affect long-term stability, fouling resistance, and filtration throughput—key factors for real-world industrial use.

Beyond the specifics of this study, it’s worth understanding why block copolymers are so widely used in advanced materials research. Block copolymers consist of two or more chemically distinct polymer blocks linked together. Because the blocks dislike mixing on a molecular level, they naturally separate into ordered nanoscale structures. Researchers can tune these structures—spheres, cylinders, lamellae, and more—by adjusting block composition, molecular weights, or processing conditions. This makes block copolymers extremely valuable for creating nanostructured membranes, photonic materials, drug delivery systems, and templated inorganic structures.

Micelles formed from block copolymers are especially useful in membrane science. In solution, they form spherical assemblies with distinct core and shell chemistries. When cast into films and processed correctly, these micelles can pack into regular patterns and then leave behind pores once certain components are removed. The resulting membranes offer very uniform pore sizes, chemical versatility, and excellent mechanical properties. The Cornell team’s innovation comes from mixing micelles with different chemistries, rather than using a single micelle type, allowing chemical heterogeneity to be built into the membrane surface.

Machine learning also plays an increasingly important role in materials science. Identifying subtle structural variations in microscopy images can be difficult, even for experts. Modern segmentation algorithms can detect micro-patterns and classify materials far faster and more accurately than manual analysis. In this case, machine learning helped pinpoint where each micelle chemistry appeared in the membrane—a task nearly impossible with traditional methods.

This entire project demonstrates the growing trend of combining self-assembling materials, computational modeling, and machine learning tools to create next-generation materials with programmable properties. As membrane technologies evolve, these interdisciplinary approaches will likely become essential.

This research not only pushes ultrafiltration forward but also illustrates how materials science is increasingly blending chemistry, physics, modeling, and data analysis to open entirely new avenues for technological innovation.

Research Paper:

Film surface assemblies from chemically distinct block copolymer micelles – Nature Communications (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65278-x