A Breakthrough Gas-Blocking Polymer Film Could Transform Electronics, Packaging, and Infrastructure

MIT researchers have unveiled a lightweight, molecularly dense polymer film that is so resistant to gas penetration that laboratory instruments cannot detect any molecules passing through it. This new material, called 2DPA-1, behaves in ways no conventional polymer ever has, offering an unusual mix of near-perfect gas impermeability, strength greater than steel, and scalable, solution-based production. Because of these combined traits, it has the potential to reshape technologies ranging from solar panels and electronics to food packaging and corrosion-resistant infrastructure.

What Exactly Is This New Polymer?

The material belongs to a rare category of two-dimensional polymers, meaning it grows in flat sheets rather than tangled chains. MIT first introduced 2DPA-1 in 2022, describing it as a polyaramid composed of repeating molecules derived from melamine, which contains a ring of carbon and nitrogen atoms. Under controlled conditions, these monomers expand outward in two dimensions instead of forming the long, spaghetti-like strands typical of plastics.

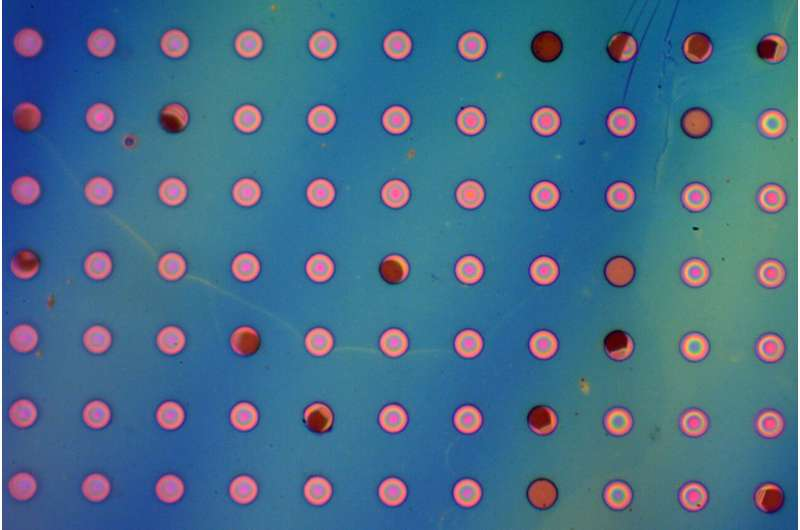

Instead of loose chains, the polymer forms nanometer-scale disks that stack tightly on top of each other. These layers hold together through strong hydrogen bonds, creating a stable and extremely compact structure with almost no internal free volume for gas molecules to sneak through. This structural property is key: while ordinary polymers allow permeation through microscopic gaps between chains, 2DPA-1’s layered packing leaves essentially no gaps at all.

The result is a polymer film that mimics certain behaviors of graphene, a crystalline material long known to be completely gas-tight — but far easier to manufacture and apply.

The Stunning Gas-Impenetrability Tests

MIT’s team tested the new films by stretching them over tiny microwells and filling them with gas to create polymer “bubbles.” Typically, bubbles made of plastic films slowly deflate over days or weeks as gases escape. But 2DPA-1 acted differently: bubbles made in 2021 are still inflated today, showing zero detectable gas loss.

To quantify this, the team exposed the films to gases including nitrogen, helium, argon, oxygen, methane, and sulfur hexafluoride. Across the board, permeability was at least one-ten-thousandth that of the best existing polymer barriers. In fact, the nitrogen permeability was so low that it fell beneath the measurable limit of laboratory instruments.

This level of impermeability is effectively unheard of in polymer science. It means 2DPA-1 performs on par with molecularly perfect 2D crystals — even though it is created through a standard solution-phase polymerization reaction rather than a high-temperature growth process.

Strength and Lightweight Construction

When 2DPA-1 was first reported in 2022, the focus was on its mechanical performance. The polymer was shown to be stronger than steel while having just one-sixth the density, thanks to its rigid molecular arrangement and layered hydrogen-bonded structure.

This makes it not only an excellent gas barrier but also a promising structural or semi-structural coating, able to withstand environmental stress without adding much weight.

Real-World Applications the Material Could Unlock

Because of its unique combination of impermeability, lightness, strength, and scalability, 2DPA-1 could transform several industries. Key potential applications include:

Longer-Lasting Perovskite Solar Cells

Perovskite solar cells are cheap, efficient, and lightweight, but they degrade quickly upon exposure to oxygen and moisture. In experiments, a 60-nanometer coating of 2DPA-1 extended the stability of a perovskite crystal to around three weeks, a significant improvement. Thicker layers could proportionally extend this lifespan even further.

Protection for Infrastructure and Vehicles

Anything exposed to the elements can corrode, oxidize, or degrade when oxygen or moisture seep in. Because 2DPA-1 can be applied as an ultrathin protective film, it has promising use cases for:

- bridges

- buildings

- railways

- ships

- aircraft

- automobiles

The film’s durability and water-rejection abilities could dramatically reduce long-term maintenance costs.

Packaging for Food, Medicines, and Sensitive Goods

Modern packaging relies heavily on multilayer polymer films that still permit some gas flow. 2DPA-1, being almost completely impermeable, could:

- extend shelf life

- reduce product spoilage

- protect delicate pharmaceuticals

- preserve flavor and freshness longer

Nano-Resonators and Communication Devices

Because the film forms stable, drum-like membranes, researchers created the first 2D polymer resonator. These nanoscale vibrating “drums” could eventually help shrink communication hardware. Current phone resonators are about a millimeter in size; a sub-micron resonator would revolutionize:

- mobile phones

- sensors

- miniature communication devices

The film’s impermeability also makes it useful for gas-sensing technologies, where tiny pressure changes must be detected accurately.

Why This Polymer Is Easier to Scale Than Graphene

Graphene has been hailed for years as a dream material, but it suffers from a major limitation: it cannot be easily produced in large sheets, and it does not naturally stick to itself when layered. Graphene layers slide over each other almost frictionlessly, making them difficult to assemble into practical coatings.

2DPA-1, in contrast:

- can be created in large quantities via solution-based chemistry

- can be spin-coated or applied like a typical polymer film

- adheres to itself through hydrogen bonding

- does not require extreme temperatures or complex vacuum systems

This gives it a practical manufacturing advantage, which is rare for materials that exhibit near-perfect barrier performance.

Broader Scientific Significance

The discovery upends long-held assumptions about what polymers can do. Traditional polymer science holds that all plastics must have at least some degree of gas permeability because of their chain-based molecular structure. 2DPA-1 shows that by forcing polymer growth into two-dimensional sheets and stacking them tightly, one can create a truly gas-impermeable material without needing a perfect crystal.

This opens the door to a potentially new class of 2D polymers that combine the convenience of plastics with the extraordinary physical properties of crystalline materials.

What Comes Next?

While the results are extremely promising, several questions remain before 2DPA-1 becomes widely adopted:

- How well does it hold up under real environmental conditions like heat cycles, abrasion, and UV exposure?

- Can the manufacturing process scale to industrial levels with consistent quality?

- What will the cost look like once production expands?

- How will it integrate with existing packaging and electronics manufacturing lines?

Future research will likely explore variants of the polymer, more durable coatings, and real-world stress testing.

Still, the discovery represents one of the most significant advances in polymer barrier materials in decades.

Research Paper:

A Molecularly Impermeable Polymer from Two-Dimensional Polyaramids (Nature, 2025)