Astronomers Reveal the Pleiades as the Core of a Vast Hidden Stellar Family

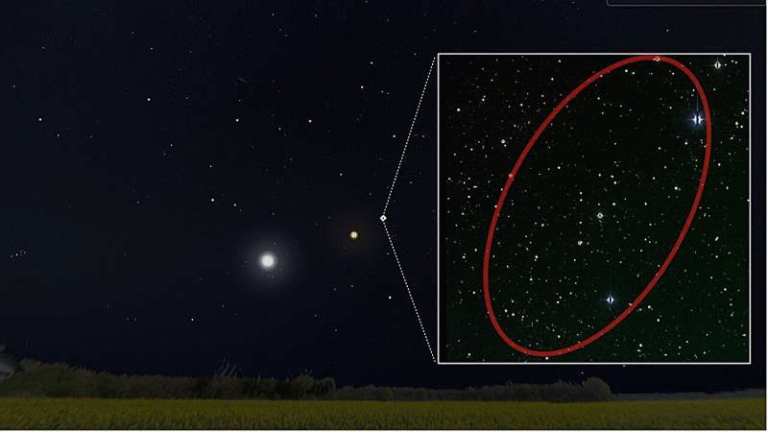

Astronomers have made a discovery that significantly reshapes our understanding of one of the sky’s most recognizable star clusters: the Pleiades, also known as the Seven Sisters. Long admired for its compact, sparkling appearance, this cluster turns out to be just the bright, central concentration of a far larger and more dispersed stellar family. Researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have identified a massive structure they now call the Greater Pleiades Complex, a revelation that expands the known size of the cluster by a factor of 20 and adds thousands of new stellar siblings that previously went unnoticed.

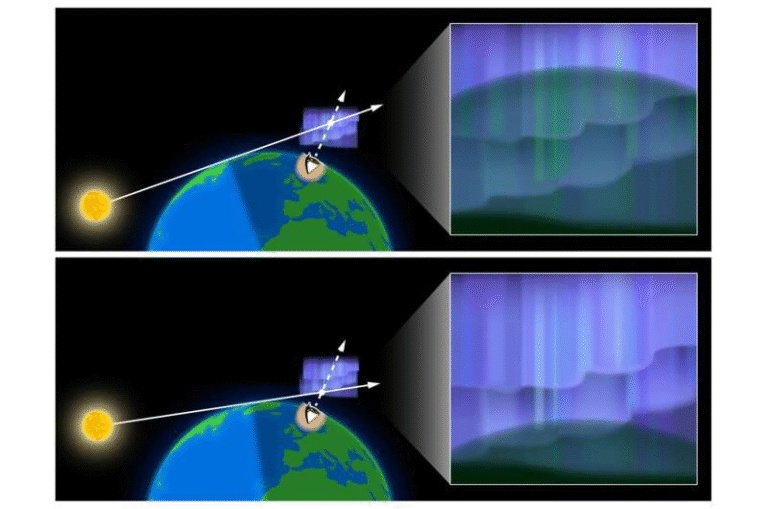

The team achieved this by combining data from two major space missions: NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope. Their analysis uncovered more than 3,000 stars that appear to share a common origin with the Pleiades, based on similar rotation rates, motion through space, and orbital history. Many of these stars are now scattered across large stretches of the sky, too spread out for traditional cluster-identification methods to recognize them as related. The researchers describe the Pleiades as the dense heart of a dissolving stellar association, one that originally formed from the same massive molecular cloud.

One of the key methods used in this study was measuring stellar rotation. Young stars rotate quickly, and because the Pleiades stars are roughly 100 million years old, they still retain distinct spin patterns that help astronomers identify their siblings. TESS provided high-precision rotation data for stars across wide regions of the sky, while Gaia offered detailed measurements of stellar movements and distances. Together, these datasets enabled researchers to track down stars that were born with the Pleiades but have since drifted far away.

To confirm the connection, the team reconstructed the likely motions of these stars over time. Through orbital traceback analysis, they found that thousands of them—now scattered over nearly 2,000 light-years—were tightly grouped in the distant past. This is compelling evidence that they originated from the same star-forming event.

The discovery carries several important implications for astronomy. First, it suggests that many well-known star clusters may be only the visible centers of much larger stellar families. Instead of being isolated groups, these clusters might be the densest remnants of associations that have already begun dispersing. The Greater Pleiades Complex reveals that stellar families can stretch across vast distances, even when only a small portion remains clustered enough to be recognizable from Earth.

This finding also offers a new way to map and understand the structure of our Milky Way. Traditional cluster identification depends heavily on positional grouping—stars that happen to be close together in the present. But associations can drift apart over time, making them nearly impossible to identify by position alone. By integrating rotation, motion, and chemical composition, astronomers now have a more robust tool for detecting hidden stellar families. This approach may uncover many more structures like the Greater Pleiades Complex, fundamentally changing how astronomers interpret the distribution and origin of stars near the Sun.

Another significant consequence is the insight this study may provide into the birth environments of stars and planetary systems. Understanding where stars formed, and with what siblings, helps scientists reconstruct the environmental conditions that shape young solar systems. Stellar siblings often share similar ages and chemical makeups, offering clues about the nurseries that formed them. With the Greater Pleiades Complex now mapped, researchers can dig deeper into how such large associations evolve, disperse, and influence the development of planetary systems—including the possibility of identifying stars that might have been part of the Sun’s own birth cluster.

The Pleiades themselves have long held an important place not just in astronomy but also in culture. Known worldwide as the Seven Sisters, the cluster appears in traditions from the Old Testament to the Talmud, is celebrated as Matariki in New Zealand, and is famously depicted in the Subaru automobile logo. This new study adds scientific depth to the cluster’s cultural resonance, showing that what humans have observed for millennia is only a small piece of a much grander stellar structure.

To provide additional background, the Pleiades cluster sits about 444 light-years from Earth in the constellation Taurus. It has been a key benchmark for studying young stars because its age, distance, and composition are relatively well understood. Before this study, astronomers recognized roughly 1,000 known members of the cluster. With the new findings, the number of related stars increases to over 3,000, and the spatial extent of the family extends far beyond what earlier telescopes could detect.

Stellar associations like the newly identified Greater Pleiades Complex offer insight into the lifecycle of star formation. Most stars form in clusters or associations within dense clouds of gas and dust. Over millions of years, gravitational interactions and galactic motion cause these associations to spread apart. Some stars remain bound in tight clusters, while others drift slowly through the galaxy, becoming nearly indistinguishable from unrelated stars. Discoveries like this one help astronomers piece together these families and reconstruct how they formed and evolved.

A noteworthy aspect of the study is the application of what researchers call the cosmic clock—the use of stellar spin rates to determine ages and origins. Since stars spin faster when young and slow down predictably over time, rotation becomes a powerful tool for tracing stellar relationships. This concept has wide potential for mapping other regions of the galaxy, especially areas where clusters have dissolved into the general stellar population.

The methods used could eventually help identify the Sun’s long-lost siblings. Our star is thought to have formed in a large stellar nursery about 4.6 billion years ago. Most of the stars that formed alongside it are now dispersed across the Milky Way. By analyzing their rotational histories, chemical fingerprints, and orbital trajectories, astronomers may one day pinpoint which stars share the Sun’s birthplace.

The discovery of the Greater Pleiades Complex represents a major step in understanding the hidden structure of our cosmic neighborhood. By revealing that the Pleiades is part of a vast, extended stellar family, astronomers are gaining a clearer picture of how stars form, move, and interact across immense distances. This research provides a framework for future studies that may uncover even more extensive stellar associations, enriching our understanding of the galaxy and the origins of stars like our own.

Research Paper:

Lost Sisters Found: TESS and Gaia Reveal a Dissolving Pleiades Complex

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae0724