Rust Formed by Microbial Life Could Be One of Our Best Clues for Finding Life Beyond Earth

Scientists are beginning to look at rust in a completely new way—not as a symbol of decay, but as a potential signature of alien life. A new comprehensive review led by Laura Tenelanda-Osorio and her team at the University of Tübingen lays out how certain microbes on Earth interact with iron to create long-lasting mineral structures. These structures, the authors argue, could be some of the most promising biosignatures to search for on Mars, Europa, and Enceladus.

This article takes a clear, straightforward approach to everything the new research says, why it matters, and how it connects to ongoing efforts in astrobiology. I’ve also included additional background knowledge on related topics so readers can walk away with a deeper understanding.

What the New Research Actually Shows

Iron is one of the most abundant elements in the solar system, and microorganisms on Earth have evolved several ways to use it for energy. Some microbes oxidize ferrous iron (Fe²⁺)—essentially “breathing” iron the way humans breathe oxygen—while others reduce ferric iron (Fe³⁺) in their metabolic processes. These redox reactions don’t happen alone; they connect directly to major environmental cycles such as carbon and nitrogen, making iron-metabolizing microbes an integral part of Earth’s biogeochemistry.

The interesting part is what these microbes leave behind. Their activity produces biogenic iron oxyhydroxide minerals, and these aren’t just random rusty deposits. Many species, particularly those living in neutral pH environments, create distinctive structures, such as:

- Twisted stalks

- Tubular sheaths

- Filamentous networks

- Mineral structures mixed with organic matter

These iron-rich deposits form as the microbes metabolize and precipitate minerals around themselves. The result is a kind of microbial “fingerprint” preserved in the geological record.

The review emphasizes a crucial advantage of these minerals: they last. Unlike many organic molecules that decay under radiation, heat, or chemical exposure, iron minerals—especially those shaped by microbial processes—can survive for billions of years. On Earth, scientists have found evidence of these signatures in environments such as:

- Hydrothermal vents

- Freshwater springs

- Acidic mine drainage systems

- Terrestrial soils

- Sediments exposed to iron-bearing rocks

Wherever water and iron interact, life tends to appear—and leave a record.

Why This Matters for Mars

Mars is arguably the most obvious testing ground for iron-related biosignatures. The planet’s well-known red color comes from oxidized iron, and evidence suggests that ancient Mars had stable bodies of liquid water, along with iron-rich sediments scattered across its surface.

If microbial life once existed on Mars, iron-based metabolism would have been an extremely accessible energy source. The byproducts—those same stalks, sheaths, or mineralized networks—may still be locked into Martian rocks.

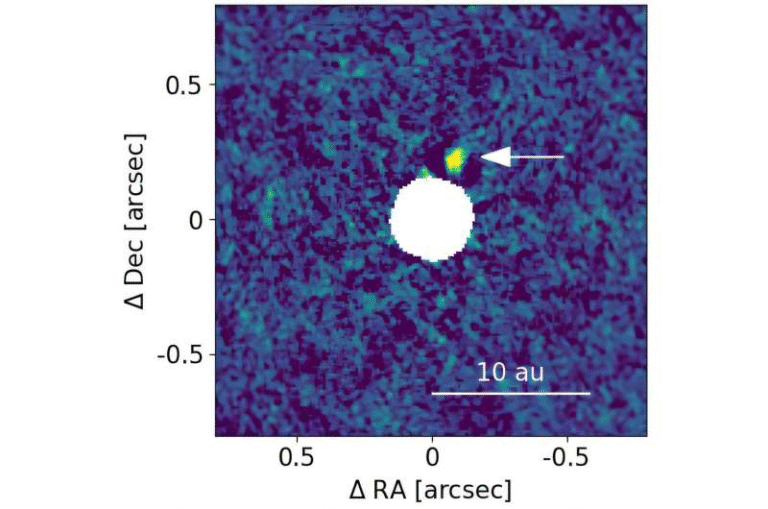

The challenge is detection. The review stresses that recognizing biological iron minerals requires more than simply identifying rust. Missions would need instruments capable of detecting:

- Morphological features (like twisted microstructures)

- Chemical compositions unique to biological activity

- Organic-mineral interactions that differ from purely geological processes

Mars rovers today can analyze rock chemistry and mineralogy, but identifying ancient microbial iron structures is a far more delicate task. It requires sub-micron imaging, spectroscopy, and possibly future sample-return missions.

Europa and Enceladus as Iron-Energy Worlds

Mars may get the spotlight, but the icy moons Europa (Jupiter) and Enceladus (Saturn) offer equally intriguing possibilities.

Both worlds hide vast subsurface oceans beneath their ice shells. Europa’s ocean likely touches a rocky seafloor, where interactions between water and rock release dissolved iron—exactly the kind of environment iron-metabolizing microbes love on Earth. Enceladus goes one step further by venting ocean material into space through its south-polar geysers. If life exists in its ocean, traces of its iron minerals might be detectable in these plumes.

Mission concepts to these moons propose:

- Flying spacecraft directly through Enceladus’ geyser plumes

- Deploying landers near active sites

- Searching for iron-bearing particles with biological textures

The review highlights that iron biosignatures could be an excellent target in such missions because mineral evidence is more resilient than organic molecules exposed to radiation and extreme cold.

How Biogenic Iron Differs From Abiotic Iron

A major point the authors make is that not all iron minerals are biological. Chemical oxidation of iron happens easily, and planetary environments could form iron deposits without any life present. So how do scientists tell the difference?

Biogenic iron is typically recognizable because:

- It forms complex and repetitive microstructures

- It often incorporates organic compounds

- Mineral precipitation patterns reflect metabolic processes rather than environmental chemistry

- The textures have architecture beyond what inorganic precipitation produces

In contrast, abiotic iron minerals usually appear as random, homogeneous aggregates without structural organization.

Future space missions would need tools capable of clearly separating biological patterns from geological ones.

Extra Insight: How Iron-Metabolizing Bacteria Work on Earth

To better understand why these structures matter, it helps to know how iron-breathing bacteria actually survive.

Iron-Oxidizing Bacteria

These microbes use dissolved Fe²⁺ as an energy source. They typically thrive where oxygen levels are low but not absent, because too much oxygen causes iron to oxidize abiotically before the microbes can use it.

Key traits:

- Often form stalk-like structures to keep themselves away from mineral precipitation

- Can build mats of iron deposits that become mineralized over time

- Play a significant role in freshwater and coastal ecosystems

Iron-Reducing Bacteria

These organisms do the opposite—they use Fe³⁺ as their terminal electron acceptor. Instead of breathing oxygen, they “breathe” ferric iron.

They are commonly found in:

- Anaerobic sediments

- Groundwater systems

- Subsurface environments where oxygen is scarce

Together, iron-oxidizers and iron-reducers create dynamic, long-lasting mineral interactions that shape ecosystems and preserve signatures in rock.

Why Iron Biosignatures Are So Durable

Iron minerals created by microbes can fossilize extremely well. Minerals like ferrihydrite, common in microbial deposits, may later transform into more stable iron oxides such as goethite or hematite without losing their original shapes.

That means ancient microbial structures can persist even through:

- Burial

- Sediment compaction

- Chemical alteration

- Reactive fluids

- Geological time scales

This durability makes them valuable for exploring planets where surface conditions may have fluctuated drastically.

The High Stakes of Finding Iron Biosignatures

The review ends with a powerful implication: discovering biogenic iron minerals on another world would do more than just prove life once existed somewhere else. It would show that Earth’s core biochemistry is not unique. If iron metabolism emerges naturally wherever water and iron interact, it suggests that life may be a common phenomenon in the universe—not a rare one.

The authors argue that future missions should be equipped to hunt for these very specific mineral structures because they might be among the best preserved pieces of evidence we could hope to find.

Research Paper Reference

Terrestrial iron biosignatures and their potential in solar system exploration for astrobiology