A Superheated Early-Universe Galaxy Is Forming Stars 180 Times Faster Than the Milky Way

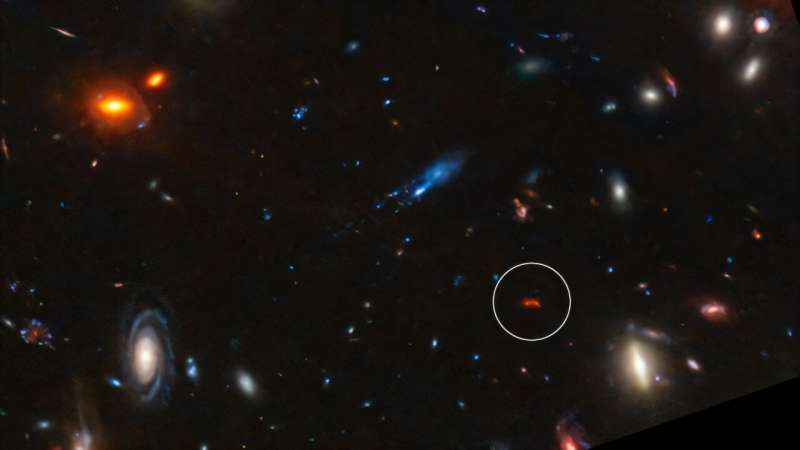

Astronomers have identified a remarkably intense star-forming galaxy from the early universe, and its discovery is helping scientists rethink how the first galaxies grew so quickly. The object, known as MACS0416_Y1 or simply Y1, sits at a staggering distance: its light has taken more than 13 billion years to reach us. That means we’re seeing it as it appeared only about 600 million years after the Big Bang, during one of the earliest chapters of cosmic history.

What makes Y1 extraordinary is not just its age but its extreme behavior. This galaxy is forming stars at more than 180 times the rate of the Milky Way, earning it the description of a superheated star factory. By studying Y1 with some of the most sensitive telescopes available, astronomers uncovered specific physical conditions that don’t resemble anything seen in our galactic neighborhood today. These findings may help solve a long-standing puzzle about how early galaxies accumulated dust and mass so quickly.

Discovery of an Extreme Galaxy in the Young Universe

Y1 was detected behind a massive foreground galaxy cluster called MACS0416, located about 4 billion light-years away in the direction of the constellation Eridanus. This cluster acts as a natural gravitational lens, magnifying background galaxies and making distant objects like Y1 appear brighter and easier to study.

The galaxy sits at a redshift of 8.3, a measurement that reflects how much the universe has expanded since the galaxy emitted its light. At such high redshift, its light is stretched so dramatically that only specialized instruments can detect it. Earlier observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) hinted that Y1 contained cosmic dust—an unusual trait this early in the universe. This caught astronomers’ attention because dust is typically produced by older stars, which shouldn’t have existed in large numbers so soon after the Big Bang.

A team led by Tom Bakx from Chalmers University of Technology set out to measure the galaxy’s dust temperature using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Their goal was to understand why Y1 appeared so bright and what that brightness revealed about its internal processes.

Measuring the Temperature of Cosmic Dust

Using ALMA’s highly sensitive Band 9 instrument, which observes wavelengths around 0.44 millimeters, the team captured Y1’s glow from tiny grains of cosmic dust heated by newborn stars. This dust shines most intensely in far-infrared and submillimeter wavelengths, well beyond what human eyes can see.

The results surprised the researchers: the dust in Y1 is heated to roughly 90 Kelvin (about –180°C). While this temperature sounds cold by everyday standards, it is significantly warmer than dust in similar galaxies the scientists have previously studied. For comparison, dust in typical star-forming galaxies often sits around 30–50 Kelvin.

This elevated temperature is a crucial clue. Hot dust emits far more light than cold dust, even if the total dust mass is relatively small. That means Y1 can appear extremely bright in far-infrared light without requiring an unrealistically large dust reservoir—a detail that offers a potential solution to a major cosmic mystery.

A Star Factory Working at Extreme Speed

The intense glow from Y1’s dust indicates an extraordinary level of star-forming activity. The galaxy is producing more than 180 solar masses of stars each year, a pace more than 100 times that of our Milky Way, which forms only about one solar mass per year on average.

This rapid star formation cannot last long on cosmic timescales. Galaxies typically experience such bursts for short periods before running out of fuel or being disrupted by internal processes such as supernova explosions. But even short-lived events like this can dramatically influence a galaxy’s development, helping it grow much faster than expected.

Astronomers suspect that galaxies like Y1 may not be rare. Instead, these intense but brief star-formation episodes might have been common in the early universe. Many of them could have gone unnoticed because their dust obscures starlight at visible wavelengths, meaning only powerful telescopes like ALMA can reveal their true nature.

Why Hot Dust Matters for Early-Galaxy Mysteries

One of the lingering puzzles in cosmology is how early galaxies accumulated so much dust. Dust is mostly produced in the outer layers of aging stars, but galaxies in the early universe are too young to have many such stars. Yet observations repeatedly showed large amounts of dust in galaxies formed within the first billion years of cosmic history.

The unusual dust temperature in Y1 offers an answer. A small amount of hot dust can emit just as brightly as a large amount of cool dust. If many early galaxies contain dust that is warmer than scientists previously assumed, then their dust masses may have been overestimated in earlier studies.

This insight helps resolve the mismatch between theoretical predictions and observations. Instead of needing vast amounts of dust produced impossibly quickly, galaxies like Y1 may simply contain modest dust quantities heated to extreme temperatures by intense, short-lived bursts of star formation.

Tools That Made the Discovery Possible

Two powerful telescopes played essential roles in uncovering Y1’s properties:

James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

- Detected Y1’s light at infrared wavelengths

- Revealed the presence of dust

- Provided high-resolution images of Y1’s structure

Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA)

- Measured Y1’s dust temperature

- Observed the dust glow at 0.44 mm

- Enabled estimates of star-formation rates and luminosity

ALMA’s location—high above sea level in Chile’s Atacama Desert—gives it a dry, stable atmosphere essential for observing faint signals from deep space.

What This Means for Our Understanding of Galaxy Formation

Y1’s extreme temperature and star-formation rate suggest that galaxies in the early universe may have evolved differently than those we see today. If galaxies commonly experienced rapid, dust-obscured bursts of star formation, then many early galaxies may be missing from current surveys simply because they’re invisible in optical light.

This discovery highlights the importance of observing the universe across multiple wavelengths. Instruments like JWST and ALMA complement each other: one captures the structure of galaxies, while the other reveals what’s happening inside dusty, hidden regions. Together, they provide a complete picture of how early galaxies grew and evolved.

The team plans to search for more galaxies like Y1 and use ALMA’s high-resolution capabilities to study their internal structure. These findings could reshape our understanding of how the first generations of stars ignited and how galaxies assembled their mass so rapidly.

Additional Context: Why Early-Universe Galaxies Are So Important

Studying galaxies from the universe’s first billion years helps answer fundamental questions such as:

How quickly did the first stars form?

Y1 suggests that some galaxies experienced powerful, short bursts of activity much earlier than expected.

How was cosmic dust produced so soon after the Big Bang?

Hot, bright dust reduces the amount of dust actually required, easing pressure on dust-production theories.

How did galaxies grow so large so fast?

Rapid, intense star-formation episodes like the one happening in Y1 can rapidly build stellar mass.

Are we missing many similar galaxies?

If they’re dust-obscured like Y1, then yes—many galaxies may be hidden from traditional surveys.

Discoveries like Y1 help refine cosmological models and offer a deeper understanding of the universe’s earliest stages.

Research Paper:

A warm ultraluminous infrared galaxy just 600 million years after the big bang

https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf1714