ESA’s Vision for Reaching Mars Highlights the Overlooked Challenges of Human Exploration

A recent science-news feature based on the European Space Agency’s ESA Strategy 2040 lays out, in very clear terms, what it will realistically take for humans to reach Mars. While Mars missions often spark images of towering rockets, futuristic colonies and heroic astronauts, ESA’s own experts stress that the real obstacles are the small, unglamorous problems hiding beneath the big-picture excitement. And according to the program manager featured in the article, these understated challenges will determine whether a crewed Mars mission can be done responsibly, safely, and sustainably.

Below is a straightforward breakdown of every specific point mentioned in the news report, followed by additional context to help readers better understand the science and engineering behind these challenges.

The Real Barriers to Mars Are the Small, Overlooked Problems

The article makes it clear that Mars exploration isn’t blocked by a lack of ambition. Rather, it’s the accumulation of technical, physiological, and psychological hurdles that make a long-duration human mission extremely difficult.

One example highlighted is spacecraft radiator systems. In space, where there is no convection or conduction, heat can only escape through radiation. If these radiators malfunction, the crew compartment can rapidly overheat. It’s not a flashy concern, but a critical one—and it represents the kind of problem that the public rarely thinks about, even though engineers obsess over it.

Other “small” but vital issues noted in the report include:

- Radiation exposure from solar storms and cosmic rays.

- Mars dust, which can interfere with machines and potentially pose health risks.

- Biological threats, including contamination risks to both Mars and Earth.

Despite being mocked by media as handling the “little things,” specialists responsible for these subtleties hold some of the most crucial roles in mission planning.

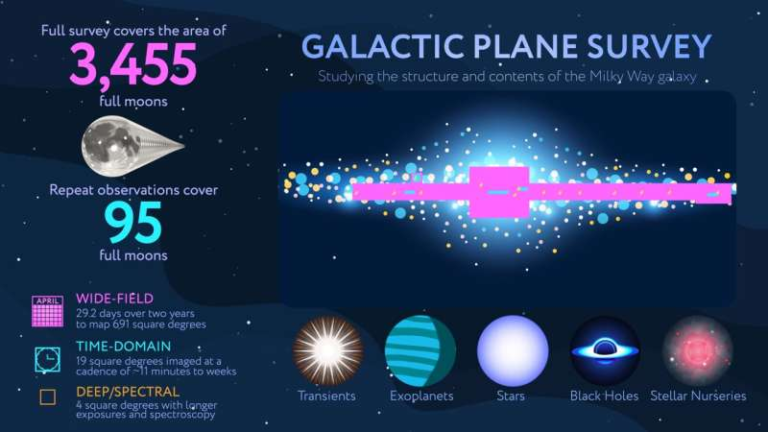

Underground Habitats Will Likely Be Essential

The feature highlights a key engineering takeaway: a Mars base will almost certainly need to be underground. That’s because Mars’ atmosphere is too thin to block dangerous radiation. According to ESA’s analysis, burying habitats beneath approximately 1.5 meters of Martian soil can provide effective shielding similar to Earth’s environment.

The report also mentions the Rosalind Franklin rover, launched in 2028, which became the first rover designed to drill to that depth. It carried the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer (MOMA) to probe subsurface materials for organic molecules. These molecules are crucial because if any life ever existed on Mars, its traces would most likely be underground, protected from radiation.

This rover, along with the joint NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return initiative, provided essential lessons. Together, they showed that reaching, collecting and even returning subsurface materials to Earth is feasible—critical steps for preparing a human mission.

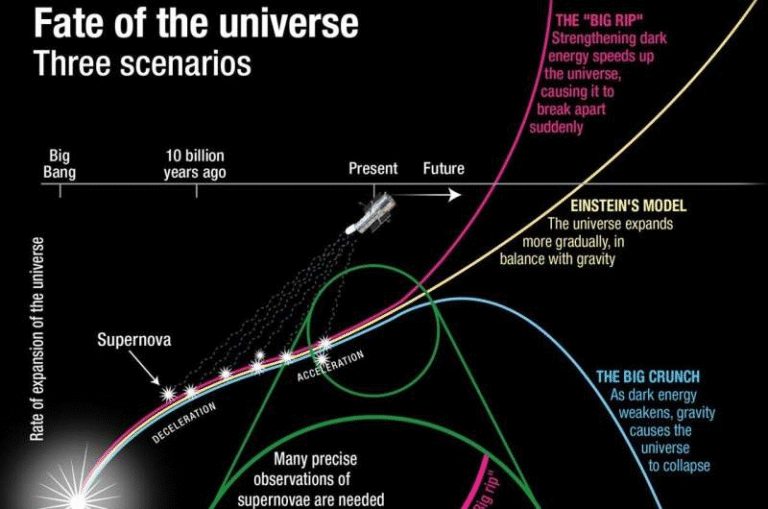

Launch Windows and Interplanetary Navigation Increase the Pressure

The article also stresses how mission timing adds another layer of difficulty. Mars missions can only be launched during narrow alignment periods—roughly every 26 months. If a mission goes wrong, the next opportunity may not come for more than two years. The article uses an example from the past: a series of SpaceX launch failures in 2025 that delayed the company’s plans to send a humanoid robot to Mars.

Unlike Earth orbit missions, interplanetary journeys require extremely precise navigation. Mars is a moving target, and even small course corrections become crucial.

Balancing Ambitions: Science vs. Colonization

The report briefly explores the competing motivations for Mars exploration. Some stakeholders prioritize scientific discovery, wanting to understand the planet’s origins and geology. Others emphasize colonization, imagining long-term human presence on the Red Planet. The article states that most people fall somewhere between these viewpoints, and ESA’s position is that both goals can coexist—provided the mission is conducted with responsibility, respect, and global benefit in mind.

Scientific Work Begins Long Before Landing on Mars

Human crews would begin experiments during the nine-month journey itself. These studies include monitoring how prolonged spaceflight affects the body, the brain and other biological systems. Since such long missions have never been attempted by humans, these observations are essential.

Once on Mars, crew members would help answer major scientific questions, particularly involving the planet’s geological history, the role of liquid water in the past, and the potential for ancient microbial life.

Planetary Protection Is Non-Negotiable

A major section of the article emphasizes adherence to COSPAR planetary protection rules. These guidelines aim to avoid contaminating Mars with Earth microbes—and to prevent any potential Martian biology from contaminating Earth when samples or humans return.

For astronauts, this means:

- Logging every piece of equipment and material they contact

- Ensuring strict containment procedures

- Avoiding unnecessary disturbance of Martian environments

ESA especially emphasizes the importance of keeping Mars as pristine as possible for scientific integrity.

In-Situ Resource Utilization Will Determine Survival

According to the ESA program manager, the crew must be able to use local Martian resources to survive and eventually return home. This includes:

- Extracting water from ice or hydrated minerals

- Producing nutrients

- Creating or sourcing building materials

Some crew members see this as a compelling engineering challenge. Others view it as a key scientific experiment to understand whether humans can genuinely live off the Martian land.

Regardless, ISRU is considered essential—shipping everything from Earth is not feasible for long-term presence.

Additional Context: Why Mars Is So Difficult for Humans

To help readers understand the broader challenges, here is more scientific background on topics referenced in the article.

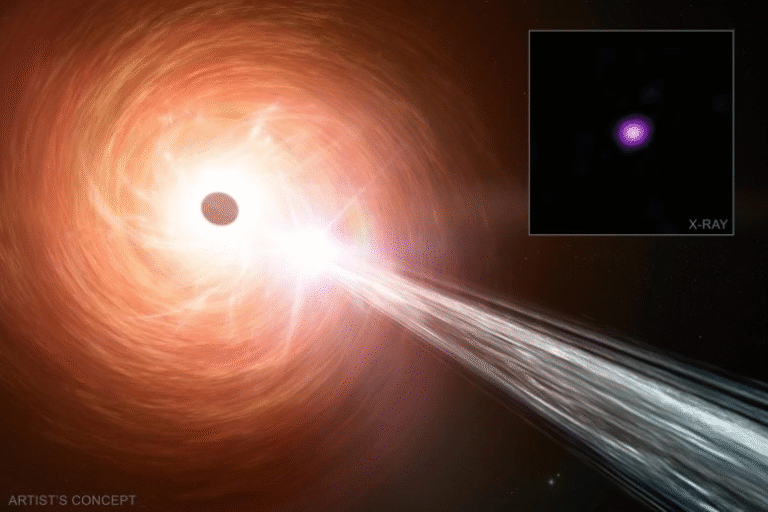

Mars Radiation Environment

Mars lacks a global magnetic field and has an atmosphere only about 1% as thick as Earth’s. This exposes the surface to:

- Galactic cosmic rays

- Solar particle events

- Secondary radiation generated when particles strike soil

Long-term exposure can cause cancer, cognitive decline, and damage to the cardiovascular and nervous systems.

Martian Dust Hazards

Mars dust is:

- Extremely fine

- Electrostatic

- Capable of damaging machinery

- Possibly harmful if inhaled

Apollo astronauts experienced respiratory irritation from lunar dust—which is similar in sharpness and chemical reactivity.

Psychological and Physiological Challenges

A nine-month journey, followed by isolation on another planet, would require:

- Managing mental health

- Handling communication delays

- Coping with low gravity and radiation

- Maintaining physical stamina in a confined space

These studies are ongoing on the ISS but have never been tested for Mars-level durations.

Why Subsurface Exploration Matters

Geologists believe Mars once had abundant liquid water, and possibly habitable environments. Any preserved organic molecules would likely be found underground, where radiation cannot destroy them.

The MOMA instrument mentioned in the article is especially relevant because it was designed for this specific purpose.