Rogue Moons Around Starless Planets Could Stay Warm and Potentially Support Life

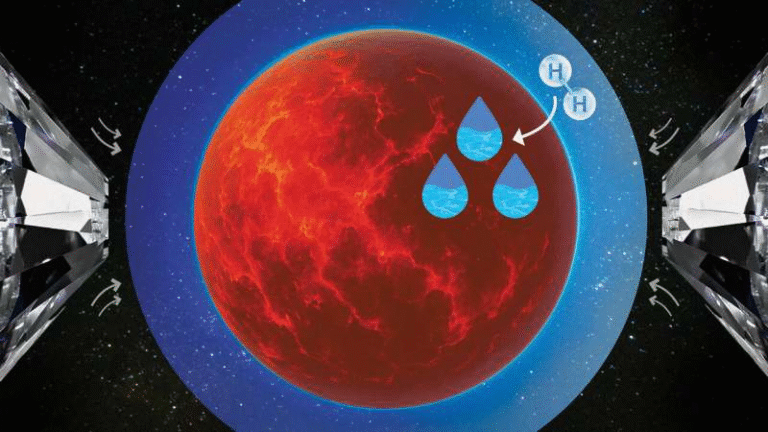

New research is opening an unexpected window into where life might arise in the universe, and it takes us far away from the warm glow of any star. A new study explores the moons of rogue planets—planets drifting freely through interstellar space after being ejected from their home systems—and shows that these moons could stay warm for billions of years through tidal heating, possibly long enough to support the earliest steps toward life.

This work comes from Viktória Fröhlich and Zsolt Regály of the Konkoly Thege Miklós Astronomical Institute in Hungary. Their study, soon to appear in Astronomy & Astrophysics, focuses specifically on what happens to planet–moon systems when their host star explodes as a Type II supernova, causing the planet to be flung into the darkness as a free-floating, unbound world. Despite the violence of that process, the simulations show something surprising: these planets can hang on to their moons.

Understanding the Idea of “Urability”

A key concept explored in the research is urability. While habitability usually refers to a world where liquid water can persist and sustain life, urability is about the minimum conditions needed for life to begin in the first place. It includes geophysical, chemical, and energetic requirements that allow life to emerge. A moon doesn’t need sunlight for urability; it needs a long-lasting source of internal heat, along with water and chemistry.

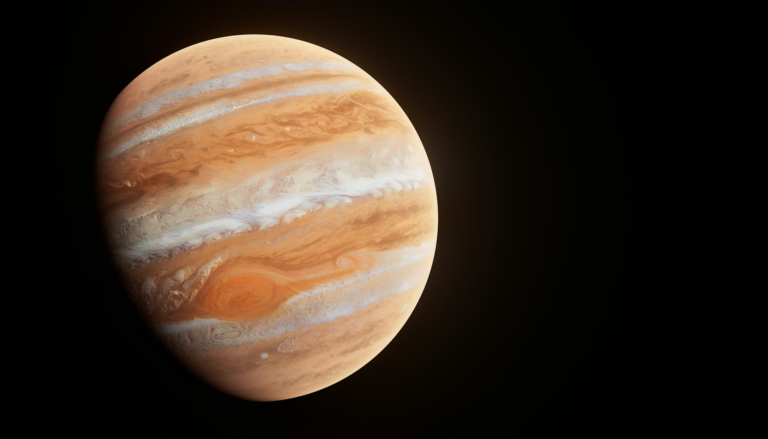

This study looks closely at whether moons orbiting a rogue planet could meet these urability conditions through tidal heating, which occurs when gravitational stretching and squeezing creates internal friction and heat. We see tidal heating in our own solar system—moons like Europa and Enceladus stay warm inside because Jupiter and Saturn constantly tug on them, maintaining their underground oceans.

The big question is: could the same thing happen even without a star anywhere nearby?

How Rogue Planets and Moons Form

Rogue planets—also known as Nomad, orphan, unbound, or free-floating planets—are surprisingly common. Observations have already uncovered hundreds, and some theories estimate the Milky Way may host two Jupiter-sized rogue planets per star. Many would naturally have moons that formed alongside them, and this study focuses on one of the clearest ways a planet becomes rogue: a supernova explosion of its host star.

When a massive star reaches the end of its life and explodes, the sudden loss of mass from the star causes nearby planets to lose their orbital anchor. Many get flung into interstellar space. What the new research investigates is whether their moons survive this dynamic upheaval—and if so, how their orbits change afterward.

What the Simulations Showed

The researchers simulated several different types of systems:

- Planets and moons starting on circular orbits

- Systems where planet and moon had pre-existing eccentric orbits

- Systems with two moons in mean-motion resonance, a configuration similar to Io–Europa–Ganymede around Jupiter

In each scenario, they also varied the velocity kick the planet receives from the supernova—essentially, how violently it gets ejected.

Across all simulations, the results were consistent: the moon stays gravitationally bound to the planet. The supernova does not rip it away. However, the moon’s orbit becomes more elliptical.

The level of this orbital eccentricity depends on the velocity kick. Their findings include:

- For initially circular orbits, moons reached an eccentricity of roughly 0.33

- Moons starting with eccentric orbits could reach about 0.88

- Moons in resonant pairs reached around 0.27

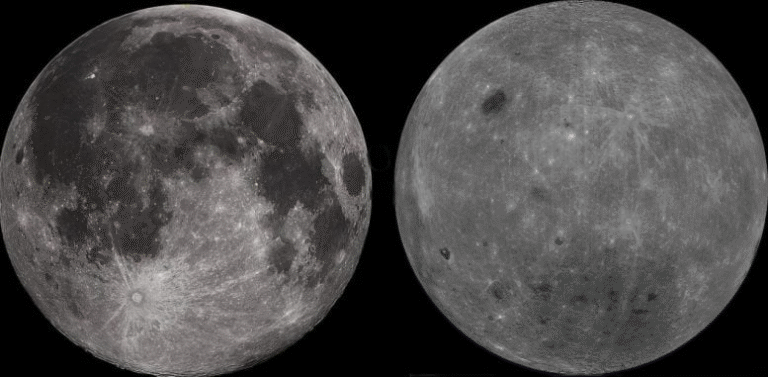

For comparison, the Moon’s eccentricity around Earth is only 0.0549, almost circular. These much higher eccentricities mean strong tidal heating—sometimes far stronger than what we see in the Solar System.

Crucially, the simulations show that moons orbiting their planet at more than 0.01 AU, with eccentricities above 0.1, can experience significant tidal heating. Between 12% and 15% of simulated rogue moons reach tidal heating levels comparable to Europa or Enceladus, in the range of 0.1–10× their estimated internal heating.

Even more significant is that the eccentricity damping timescales are extremely long—billions of years, longer than the age of the Solar System. This means these moons stay warm for a huge span of time, giving them a stable energy source even deep in interstellar space.

What This Means for Life

If these moons can keep internal oceans liquid for billions of years, they become very interesting places in the search for life. They may never see sunlight, but they could have:

- Subsurface oceans

- Rock–water interactions

- Long-lasting, stable heat

- Energy gradients, essential for chemistry

In many ways, they would resemble Europa, Enceladus, or Titan—moons that many scientists believe could already host microbial life today.

The new twist is that these environments could exist in total darkness, entirely independent of a parent star. This challenges the long-held assumption that stars are central to the emergence of life.

The researchers also note that their findings apply beyond the supernova scenario. Rogue planet–moon systems can also be created through early planetary instability, interactions with other planets, or stellar flybys. In each case, the tidal-heating mechanism remains the same.

With some theoretical models suggesting trillions of rogue moons in the Milky Way, this could represent one of the galaxy’s largest hidden habitats for potential life.

Can We Detect Rogue Moons?

Right now, detecting even a rogue planet is difficult, but not impossible. Detecting a moon around one is much more challenging—but not out of reach.

Some possibilities include:

- Transit detection

Large moons like Titan or Ganymede block about 2% of their planet’s light when transiting. If similar moons exist around rogue giants, their transit signal might be faint but detectable. - Gravitational microlensing

A rogue planet–moon system passing in front of a background star could momentarily brighten the star’s light. This requires a lucky alignment but is considered possible.

Upcoming observatories like the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will greatly improve our chances by scanning massive areas of the sky with high precision.

For now, rogue moons remain undetected, but the technology is catching up, and theoretical groundwork like this new study helps guide future searches.

Why This Research Matters

This study reshapes our thinking in several important ways:

- Life might arise in places completely independent of starlight.

- The number of potentially life-supporting worlds could be much larger than planets in habitable zones.

- Moist, warm environments might exist inside objects we never considered before.

- Rogue planets and moons may be major players in the universe’s biological landscape.

As the authors emphasize, an eccentric moon expelled into interstellar space could remain warm, geologically active, and potentially urable for billions of years.

It’s a reminder that nature often works in ways we don’t expect—and the galaxy may be teeming with hidden, dark worlds that are far more alive than we once imagined.

Research Paper

Life in the dark: Potential urability of moons of rogue planets

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.03392