How Three Runaway Stars Helped Astronomers Pin Down the Large Magellanic Cloud’s Mysterious Past

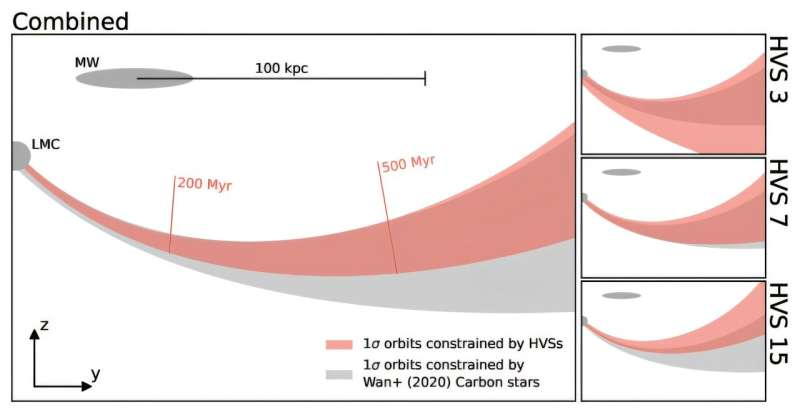

Astronomers have been trying to figure out the true orbital history of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) for decades. Even though it’s one of our closest galactic neighbors, its past motion through space has been surprisingly difficult to track. A new study by Scott Lucchini and Jiwon Jesse Han from the Harvard Center for Astrophysics takes a fresh, clever approach to this long-standing problem: instead of focusing solely on the LMC itself, the researchers used three runaway stars—also known as hypervelocity stars (HVSs)—to retrace the galaxy’s recent path.

This method might sound unusual, but it turns out to be incredibly powerful for probing galactic motion, dark matter interactions, and even the long-debated question of whether the LMC contains a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at its center. Below is a clear breakdown of what the study reports, why these stars matter so much, and what this means for our understanding of galaxies.

What Exactly Are Hypervelocity Stars?

A hypervelocity star is essentially a star moving so fast—often above 1,000 km/s—that it can escape the gravitational pull of its home galaxy entirely. These stars are extraordinarily rare, and the most widely supported explanation for how they form is the Hills mechanism. This process occurs when a binary star system wanders too close to a supermassive black hole. The black hole’s immense tidal forces rip the pair apart, capturing one star while violently ejecting the other.

Because these ejected stars are flung out in a very specific direction from a very specific location—the immediate environment around a black hole—they provide something like a cosmic arrow pointing back to their origin. Track that arrow far enough back, and you can figure out where and when the star began its high-speed journey.

This is exactly what the authors of the study set out to do.

The Three Stars That Changed the Picture

Using Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3), the researchers identified three hypervelocity stars—HVS 3, HVS 7, and HVS 15—that appear to have been ejected not from the Milky Way, but from the LMC.

- HVS 3 has been a strong LMC candidate for years.

- HVS 7 and HVS 15 were more recently discovered and show trajectories that do not match an origin in the Milky Way.

- Their motion is best explained by being launched from within the LMC, likely by an SMBH.

This alone is a big deal because the presence of hypervelocity stars from the LMC provides strong indirect evidence that the LMC does contain a supermassive black hole, something astronomers have debated for a long time. The study doesn’t directly image the black hole, but the motion of these runaway stars acts as the next best thing.

Reconstructing the LMC’s Path Through Space

If these stars really came from the LMC, then each one’s trajectory is like a line drawn backward through the galaxy’s past position. But tracing that line accurately is much harder than it sounds.

Galaxies are not on simple, straight paths. Their motion is influenced by:

- interactions with each other,

- the gravitational pull of the Milky Way,

- the invisible mass of dark matter,

- and dynamical friction, which acts like a drag force as galaxies move through dark matter halos.

Taking all this into account, the authors ran simulations of the motion of both the LMC and the Milky Way, inserting realistic models of dark matter and dynamical friction. By intersecting those simulations with the backward-integrated paths of the three HVSs, they were able to reduce the possible orbital “corridor” of the LMC over the past few million years by about 50%.

This doesn’t solve every puzzle, but it’s a major improvement in tracking where the LMC has been.

The First Passage vs. Second Passage Debate

One of the big remaining debates in galactic astronomy is whether the LMC is:

- on its first-ever orbit around the Milky Way (the First Passage model), or

- completing its second full orbit, meaning it swung past us once already about 6–8 billion years ago (the Second Passage model).

Both scenarios significantly change how we understand the structure of the Milky Way’s halo, the distribution of its dark matter, and the history of the Magellanic Clouds.

Unfortunately, even with the new constraints, the researchers couldn’t decisively rule out either model. Their results are consistent with simulations supporting both possibilities, though they note that Second Passage models tend to be less robust when tested against the complexity of real galactic dynamics.

Still, the refined orbital corridor provides much tighter boundaries for future studies.

Locating the LMC’s Hidden Black Hole

Perhaps the most attention-grabbing result from the study is that the authors provide specific coordinates for where the LMC’s supermassive black hole is most likely located right now. And interestingly, it doesn’t sit exactly at the visible center of the galaxy.

Instead, it appears to be offset by about 1.5 degrees from the LMC’s photometric center. That might sound small, but on galactic scales it’s a significant displacement. The likely cause is the chaotic gravitational interaction between the LMC and its smaller companion, the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), which has been tugging at it for billions of years.

The idea that the LMC’s central black hole is displaced due to tidal interactions is not new, but these new hypervelocity star trajectories offer some of the strongest evidence yet.

The Limitations of the Study

Despite these exciting results, the authors acknowledge several important caveats:

- The conclusions rely on only three stars with currently usable data.

- The stars’ proper motions still have uncertainties, and improving them would require more telescope time.

- Modeling galactic motion over millions of years is inherently complicated, especially when dark matter is involved.

- Some alternative explanations—like dynamical ejections from star clusters—cannot be entirely ruled out yet.

Future Gaia releases and targeted observations could greatly strengthen the method.

Why This Matters for Astronomy

The implications of this research reach far beyond just one galaxy.

- A New Way to Trace Galactic Motion

Using hypervelocity stars as “breadcrumbs” for reconstructing galactic orbits is a powerful new technique. It could be applied to other galaxies if enough runaway stars can be identified. - Evidence for a Supermassive Black Hole in a Dwarf Galaxy

Confirming an SMBH in the LMC would significantly expand our understanding of how widespread such black holes are, especially in smaller galaxies. - Better Understanding of Dark Matter

Because the method involves modeling how galaxies move through dark matter, it indirectly helps test how dark matter interacts with normal matter on large scales. - Refining the LMC’s History

The LMC heavily influences the structure of the Milky Way’s outer halo, and knowing its past orbit helps refine models of our galaxy as a whole.

This study is a major step forward, even with its limitations. With more hypervelocity stars and more precise measurements, astronomers may soon be able to draw an even sharper picture of the LMC’s journey—and finally confirm whether it’s truly on its first swing past the Milky Way or returning for round two.

Research Paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.03393