NASA’s Leadership Crossroads and the Bold, Controversial Vision That Could Reshape Its Future

NASA is heading into a pivotal moment. With major missions approaching and a wave of political pressure shaping the direction of U.S. space exploration, the agency now finds itself balancing internal uncertainty, external expectations, and a changing national agenda. The biggest question at the center of it all is who will permanently lead the world’s most influential space organization—and what vision that person will bring.

Right now, the spotlight is on Jared Isaacman, the billionaire entrepreneur best known for funding and flying on two privately financed orbital missions with SpaceX. His nomination to serve as NASA Administrator was first submitted by President Donald Trump on his first day in office, withdrawn amid political tension in May, and then unexpectedly revived this month. In his absence, Sean Duffy, who already serves as Transportation Secretary, stepped in as acting NASA administrator. For months, Duffy was even pushing for the permanent job, creating an unusual period of overlap and rivalry within the agency’s leadership.

Policy analysts, including Casey Dreier of the Planetary Society, say the situation looks more stable now than it did earlier in the year—though still uncertain. Dreier suggests Isaacman is likely to pass his next Senate confirmation hearing, given his generally positive reception the first time around and the fact that he doesn’t bring hostility toward NASA or scientific institutions. Yet his confirmation won’t come without tough questions, especially because of a controversial internal document connected to him.

That document—called Project Athena—is a 62-page proposal outlining Isaacman’s personal vision for NASA’s future. It was leaked to the press after his nomination was withdrawn, reportedly by Duffy himself as a strategic move. The report is packed with ideas that have stirred meaningful debate inside NASA, throughout Congress, and across the broader space community.

Project Athena proposes shifting more responsibility from government-operated NASA centers to commercial partners. This includes moving certain space science missions, traditionally built and controlled by NASA, into the hands of private companies. It also pushes the idea that NASA shouldn’t remain heavily involved in what Isaacman calls the “taxpayer-funded climate science business,” redirecting Earth and climate research to universities and other scientific institutions. In addition, the plan raises doubts about the long-term funding for both the Space Launch System (SLS)—NASA’s multi-billion-dollar heavy-lift rocket—and the planned Gateway lunar outpost, a small station intended to orbit the Moon and support Artemis missions.

These recommendations align closely with the Trump administration’s budget priorities, which currently propose cutting NASA’s total funding by 24% in 2026 and slashing the science division’s budget by 47%. Cuts of that scale would impact dozens of ongoing missions, including the Mars Sample Return, the Juno mission at Jupiter, and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, leaving Isaacman—if confirmed—to navigate the political fallout between Congress and the White House.

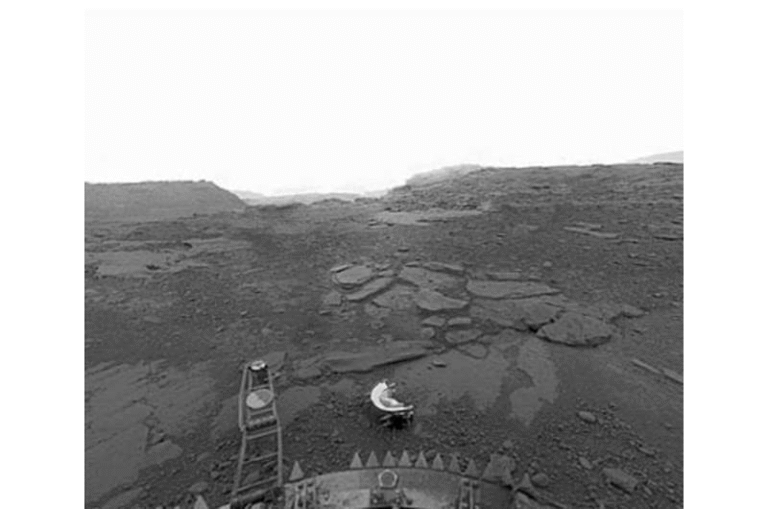

Project Athena also calls for NASA to evaluate the necessity of its major research centers, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). The report poses direct questions, such as what is tangibly “built” at JPL, a jab that sparked immediate criticism given JPL’s long history of engineering robotic missions that have explored the solar system.

After the leak, Isaacman posted a lengthy explanation on X, stressing that some parts of the document were outdated and that he never intended for Athena to be used to close NASA centers or cancel programs prematurely. He defended the report as an early attempt to map a more efficient long-term strategy for NASA, citing his belief in improving political processes and supporting the agency’s future success.

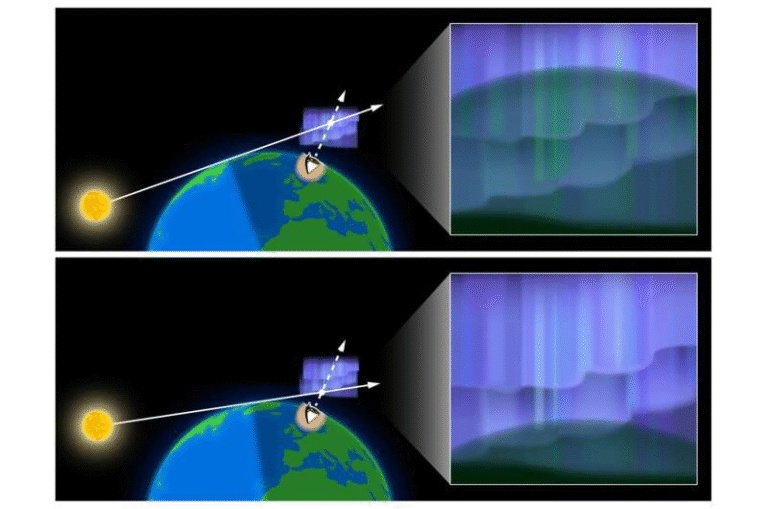

While Isaacman’s critics focus on the risks of his proposals, some experts—including Dreier—say parts of Athena are promising. For example, the emphasis on nuclear electric propulsion is widely seen as an essential technology for long-duration missions, potentially enabling faster and more energy-efficient travel to the outer solar system. Dreier believes this focus could be a valuable legacy if Isaacman manages to push those ideas forward.

But even if Isaacman is confirmed, he will face major questions about NASA’s direction—especially regarding the Artemis program. NASA’s current plan aims to land astronauts on the Moon with Artemis III in 2027, using a human landing system built by SpaceX’s Starship. However, acting Administrator Duffy recently suggested that schedule might slip to 2028, and also raised the possibility of reconsidering SpaceX’s role entirely. He stated that the agency may need to open the landing contract to more companies to accelerate the lunar timeline, especially given concerns that China could reach the lunar surface first. In response, SpaceX has promised to develop a more “simplified” version of Starship for the mission.

A key decision for the next administrator will be whether to continue relying heavily on SpaceX or shift more responsibility to competitors like Blue Origin. This is especially sensitive because Isaacman has close ties to SpaceX: he’s collaborated with them on two orbital missions and reportedly invested tens of millions of dollars into their work. His earlier nomination ran into political resistance partly because of concerns over a potential conflict of interest. During his first confirmation hearing, he emphasized that NASA must remain the customer and that contractors must work for the agency—not the other way around. These questions will resurface during his second hearing.

Another major question concerns whether NASA’s primary focus should remain on the Moon or expand toward Mars. The current administration is determined to plant the American flag back on the Moon before China does, but Trump has long been vocal about his desire to reach Mars. SpaceX has floated the idea of sending a robotic Starship to Mars in 2026 or 2028, though this timeline is widely considered overly optimistic. Project Athena references something called Project Olympus, which appears to involve developing technologies to support future human landings on Mars. If Isaacman becomes administrator, he may face pressure to accelerate progress in that direction.

Underlying all of this is a broader concern: the risk of NASA becoming too dependent on a small number of commercial partners—especially on a single company like SpaceX. Dreier warns that if Moon missions and major deep-space objectives rely entirely on one private vendor, national goals could rest on the success or failure of that company’s internal operations. He also worries that a NASA largely focused on the Moon and Mars could leave large parts of the scientific community behind. While commercial companies have excelled in transportation, they have not built planetary probes, atmospheric instruments, or interplanetary science missions the way NASA has. If scientific roles shrink dramatically, Dreier questions where the next generation of scientists will go.

NASA’s future leadership and direction are now at a critical turning point. The next administrator will need to balance political expectations, scientific priorities, commercial partnerships, and international competition—all while steering an agency that has more responsibilities, more public visibility, and more strategic importance than ever before.