A Newly Discovered Hidden Water-Saving Mechanism in Leaves Could Help Future Crops Survive Drought

Cornell University researchers have uncovered a previously unknown way that plants regulate water inside their leaves, and the discovery is significant enough that it may eventually reshape how plant biology is taught. For decades, scientists believed that stomata—the tiny pores on leaf surfaces—were the plant’s sole regulators of water loss. These pores open to let carbon dioxide in for photosynthesis and close to prevent water from escaping when conditions are dry. But now, thanks to an advanced nanosensor technology, a second and deeper water-control system inside the leaf has been revealed.

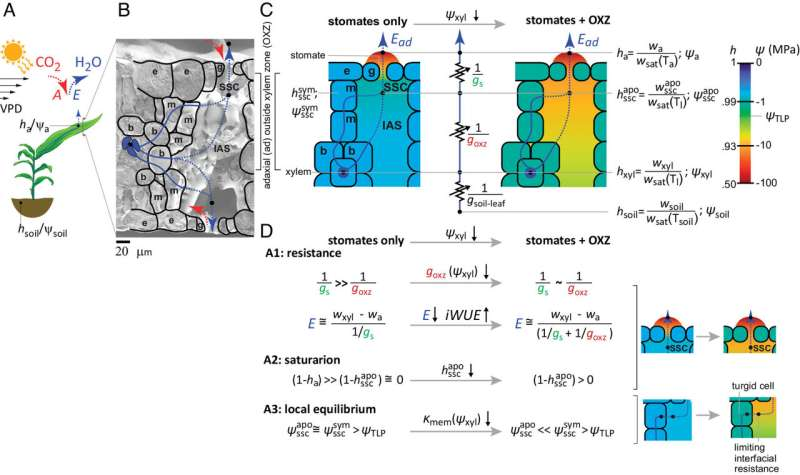

This new mechanism functions beneath the leaf’s surface, at the membranes of photosynthesizing mesophyll cells. It helps determine how much water moves from the inside of the leaf to the spaces where evaporation occurs. The discovery came from a study led by Cornell engineer Abe Stroock, along with researchers Sabyasachi Sen and Piyush Jain. Their work, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how water regulation within the leaf is much more complex—and potentially more useful for crop breeding—than previously understood.

How Water Travels Through a Leaf

To understand why this discovery matters, it helps to know how water normally moves in plants. Water is absorbed by the roots and pulled upward through the xylem, a specialized vascular tissue. Once in the leaf, the water travels outward until it reaches the mesophyll layer, which is the main site of photosynthesis.

From there, water evaporates into tiny intercellular air spaces inside the leaf, and then exits through the stomata as vapor. This whole process—called transpiration—is crucial for nutrient transport, temperature control, and overall plant health. Until now, scientists assumed that the mesophyll cells and the surrounding air spaces had roughly the same water status. The expectation was that the evaporation point inside the leaf was always near full humidity.

But the new findings challenge this long-standing assumption.

What the Study Revealed

Using the new nanoscale sensor, the researchers found that mesophyll cells can stay fully hydrated even when the tiny air pockets around them become extremely dry. This difference in water levels shows that the membranes of the mesophyll cells create resistance to water flow. In other words, the inside of the leaf acts as a second checkpoint—a hidden regulator—controlling how much water escapes to the air spaces before reaching the stomata.

This phenomenon occurs within the last 100 microns of the water’s journey from root to atmosphere. That distance is extremely small, but the impact is large. When the membrane conductance drops, water flow slows down before it even reaches the stomata. This means the leaf can limit water loss without needing to close its stomata as tightly as it normally would.

The researchers described this as nonstomatal control of transpiration, a concept that had little direct evidence until now. The ability to measure it so precisely became possible due to the development of a unique Cornell innovation: AquaDust.

How the AquaDust Sensor Works

AquaDust is a soft nanoscale gel that fits inside the intercellular air spaces of leaves without damaging their structure. It contains fluorescent dyes that change their behavior depending on how hydrated the surrounding environment is. When water levels drop or rise, the gel swells or shrinks accordingly, and the dyes emit different signals.

These signals can be detected using fiber optics or fluorescence microscopy. This gives researchers a dynamic, real-time view of water status inside the leaf—something that was impossible with older methods.

Without AquaDust, the mismatch between mesophyll hydration and air-space dryness would have remained hidden. For the first time, scientists could see exactly where water stress develops inside living leaves.

Why This Discovery Matters for Drought-Resistant Agriculture

Plant breeders have long struggled with a major trade-off: when stomata close to conserve water, they also restrict carbon dioxide intake. That means the plant grows more slowly. Improving water-use efficiency without harming photosynthesis has been considered extremely difficult.

This new internal regulation mechanism offers a potential workaround. If breeders can identify and select for traits that strengthen this nonstomatal water-blocking ability, plants may conserve water internally while still keeping stomata open enough to allow carbon dioxide in.

The research team is already collaborating with Corteva Agriscience to explore how this trait appears in maize, one of the world’s most important crops. If genes responsible for this internal control can be identified, it could help breeders create crop varieties that stay productive even during droughts.

This is especially relevant in the context of global climate change, where many regions face more frequent dry spells and unpredictable weather patterns.

What We Still Don’t Know

Although the discovery is promising, several questions remain:

- Scientists do not yet know the specific genes or molecular structures responsible for the membrane-level water resistance.

- The current measurements were taken in controlled lab conditions. Farmers need to know whether this mechanism works reliably under variable real-world stresses such as soil dryness, heat waves, and fluctuating humidity.

- Researchers need to understand whether this trait is present in many species or only in particular crops.

- Potential trade-offs—such as effects on leaf temperature or energy use—must be investigated.

These questions will guide future research as scientists explore how universal and useful this internal water-control system may be.

Additional Background: Why Water-Use Efficiency Is Critical

With the global population rising and climate extremes becoming more common, improving agricultural resilience is one of the biggest scientific challenges of the century. Crops that can grow with less water are essential in regions facing declining rainfall and increasing heat.

Water-use efficiency (WUE) refers to how well a plant converts water into biomass or grain. Traditionally, breeders have improved WUE through:

- Root traits, such as deeper or more branched root systems

- Stomatal traits, such as faster stomatal response

- Leaf surface features, such as waxy coatings

But internal water control at the mesophyll level introduces a completely new dimension. Since this mechanism does not restrict photosynthesis as much as stomatal closure does, it represents a promising direction for future crop improvement.

Additional Background: What Are Mesophyll Cells?

Mesophyll cells make up the majority of the leaf’s interior. They are packed with chloroplasts, where photosynthesis happens. These cells exchange gases with the internal air spaces and constantly pass water outward as part of the transpiration stream.

The membranes surrounding these cells are typically thought of as passage points for water. This new research shows these membranes can adjust their conductance, changing how water flows into the air spaces. This challenges the idea that evaporation inside a leaf is always at maximum humidity and controlled only by stomata.

Additional Background: Transpiration and the Plant Water Path

Transpiration is the process in which water moves from soil to leaf to atmosphere. It does much more than simply release water vapor. It helps:

- pull nutrients upward from the soil

- cool the plant

- maintain leaf structure

- support photosynthesis through CO₂ intake

The discovery that a major control point lies just before water evaporates changes how scientists might model or teach the entire water-transport pathway.

Research Paper Reference

Loss of conductance between mesophyll symplasm and intercellular air spaces explains nonstomatal control of transpiration

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2504862122