Light-Controlled Synthetic Embryos Reveal How Mechanical Forces Shape Early Human Development

Researchers have taken a significant step forward in understanding one of the most mysterious moments in human development: gastrulation, the stage roughly two weeks after fertilization when a flat sheet of cells transforms into the layered blueprint of the human body. This brief but essential process establishes the head–tail, ventral–dorsal, and left–right axes that guide all future growth. Because it occurs so early and deep inside the uterus, it has remained largely inaccessible to direct study. But now, a new approach using light-controlled synthetic embryos has opened an unprecedented window into how humans begin to take shape.

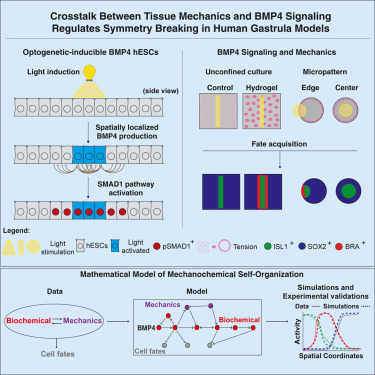

A team at Rockefeller University has developed an optogenetic system that allows them to activate crucial developmental proteins, especially BMP4, with precise flashes of light. Their goal: to test whether biochemical signals alone can drive gastrulation or whether physical forces within tissues also play a crucial role. What they found is that chemical cues, although essential, simply are not enough. Gastrulation begins only when cells experience the right mechanical conditions, revealing a deep interplay between molecular signaling and tissue mechanics.

The synthetic embryo platform is built by engineering human embryonic stem cells with a genetic switch that permanently turns on BMP4 when exposed to a specific wavelength of light. This lets researchers control exactly when and where the signaling begins, something that is impossible in an actual embryo. It also allows them to test how factors such as tissue geometry, mechanical tension, and confinement influence the developmental cascade.

When BMP4 was activated in open, low-tension environments, the stem-cell clusters were able to produce extra-embryonic cell types, like those forming the amnion. But they failed to generate mesoderm and endoderm, the internal layers that later produce organs such as the heart, lungs, gut, and muscles. This showed that BMP4 alone cannot initiate full gastrulation. However, when the researchers activated BMP4 at the confined edges of cell colonies or within tension-inducing hydrogels, the missing layers finally formed — revealing that mechanical forces are indispensable for proper development.

The study also showed how mechanical signals interface with known biochemical pathways. A key player is YAP1, a mechanosensory protein whose levels inside the nucleus respond to physical tension. YAP1 functions like a developmental brake, preventing gastrulation from occurring prematurely. Only when mechanical tension rises and YAP1 levels shift does the downstream network of WNT and Nodal signaling pathways activate correctly, instructing the tissue to form the proper germ layers. A previous study from the same research group highlighted YAP1’s influence on self-organization in patterned stem-cell cultures, and this new work extends that understanding into a more realistic embryo-like context.

The experiments were complemented by a mathematical model created by co-first author Laurent Jutras-Dubé. This “digital twin” simulates how chemical signals spread through tissue while interacting with mechanical constraints. When fed real measurements of mechanical tension, the model accurately replicated the experimental outcomes, confirming that mechanics and biochemistry must work together for symmetry breaking and germ-layer formation. This gives researchers a quantitative tool to predict how embryos organize themselves and offers a new framework for studying early development.

These findings build on earlier achievements from the Brivanlou lab, which, in 2014, demonstrated that human embryonic stem cells grown on microchips could self-organize into two-dimensional gastruloids mimicking early developmental patterns. The new optogenetic system takes that work further by offering high-precision control over cellular signaling and physical environment, bringing the models closer to real embryonic behavior.

Looking ahead, the team plans to investigate whether embryos possess a mechanical organizer — a structural counterpart to biochemical signaling centers that might physically coordinate early development. They propose that embryos must achieve both chemical readiness and mechanical competence before key milestones can occur. If confirmed, this would reshape how scientists think about developmental checkpoints.

Beyond basic science, the implications are wide-ranging. Understanding the mechanical and biochemical conditions needed for gastrulation could shed light on why some pregnancies fail very early, before implantation or shortly after. It could guide improvements in fertility treatments, regenerative medicine, and stem-cell engineering, especially for generating tissues that require specific mechanical cues to form correctly. The optogenetic embryo system also offers a platform for testing how engineered microenvironments influence development, potentially enabling therapies where stem cells activate only under controlled conditions.

To appreciate the significance of this work, it helps to understand why gastrulation has long been called the “black box” of human development. In most animals used for research — like frogs, zebrafish, and chicks — embryos develop externally, making it easier to observe how chemical gradients, tension patterns, and tissue flows guide the formation of germ layers. In these models, mechanical forces have been known to influence development, but translating those findings to humans has been difficult. Human embryos are smaller, develop inside the uterus, and ethical boundaries limit how far scientists can observe them. Therefore, creating accurate lab models is crucial.

This new system addresses many of those limitations by combining three powerful elements: optogenetics, engineered microenvironments, and computational modeling. With optogenetics, researchers can activate only a subset of cells with pinpoint accuracy. With microenvironments, they can physically confine or relax tissues to mimic different developmental conditions. With modeling, they can test how various forces and signals interact. Together, these approaches bring scientists closer than ever to a controllable, high-fidelity model of early human development.

Another interesting part of this research is what it suggests about the nature of developmental robustness. Embryos must develop reliably despite variations in environment and genetics, and this robustness may come from the interplay between mechanics and biochemistry. Mechanical forces may act as a stabilizing factor, ensuring that signaling pathways activate properly even when biochemical cues fluctuate. This aligns with findings from other areas of biology where cells use mechanical feedback to maintain stability during tissue formation, wound healing, and organ development.

The discovery could also influence how scientists think about engineering tissues from stem cells. Many attempts to create organoids or artificial tissues in the lab rely heavily on chemical signals but neglect the role of mechanical stress, tension, and spatial confinement. The new findings suggest that achieving the right physical context may be just as important as choosing the right molecular cues. This may help improve the formation of complex tissues such as heart muscle, kidney structures, and neural layers.

Overall, this study highlights a fundamental truth: human development is not solely a biochemical process. It is a mechanochemical process, requiring both signals and forces to work in harmony. By showing how gastrulation depends on this partnership, the researchers offer a new perspective on where we all come from — a perspective that is both scientifically fascinating and deeply human.

Research Reference:

Crosstalk between tissue mechanics and BMP4 signaling regulates symmetry breaking in human gastrula models