New Scientific Update Reveals Surprising Details About Cleveland’s Prehistoric Sea Predator Dunkleosteus

A fresh scientific investigation has taken a deep dive into Dunkleosteus terrelli, the massive armored predator that dominated the seas around 360 million years ago, and the results are reshaping what we thought we knew about this ancient giant. Although the species has been a favorite among paleontologists and museum visitors for more than a century, it turns out that Dunkleosteus was far more unusual—and far more advanced—than long-standing research suggested. This new study fills a 90-year gap in scientific understanding, offering the most detailed look yet at the anatomy, jaw mechanics, muscles, and evolutionary role of this remarkable fish.

Below is a straightforward breakdown of everything the new research uncovered, along with additional context that helps explain why Dunkleosteus remains one of the most fascinating creatures of the Devonian seas.

A Clearer Look at a Legendary Sea Monster

Dunkleosteus terrelli, measuring roughly 14 feet long, was one of the largest predators of the Late Devonian period. It belonged to a group of extinct armored fishes called arthrodires—often described as shark-like but equipped with heavy bony armor around the head and torso. Unlike modern sharks, which have teeth, Dunkleosteus sliced its prey using razor-sharp bone blades, making it one of the most efficient killing machines of its era.

Its fossils, mostly preserved in the shale deposits around present-day Cleveland, have been known since the 1860s, and casts of its skull and jaw pieces can be found in museums worldwide. Despite this fame, Dunkleosteus has been scientifically neglected for almost a century. The last major study of its jaw anatomy was published in 1932, when knowledge of arthrodire anatomy was still extremely limited. That research focused largely on how the bones fit together, not how the muscles, cartilage, and overall structure functioned.

Now, an international research team has revisited the anatomy of Dunkleosteus using modern paleontological understanding, updated comparisons with better-preserved arthrodire fossils from Australia, and access to the largest and best-preserved collection of Dunkleosteus specimens at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Their findings provide the most complete picture yet of how this ancient giant actually operated.

Surprising New Anatomical Discoveries

The updated analysis uncovered several important details that significantly refine earlier assumptions:

A Skull Made Largely of Cartilage

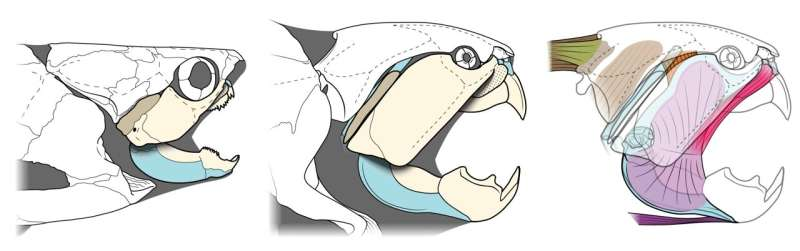

One of the most striking discoveries is that nearly half of the Dunkleosteus skull was made of cartilage, not bone. This includes many of the most important joints and muscle-attachment points in the jaw. Previous reconstructions depicted a mostly bony skull, but the new research shows a structure more flexible and specialized than previously believed.

Shark-Like Jaw Muscles

The study also identified a major bony groove in the skull that housed a large facial jaw muscle similar to those in modern sharks and rays. This is one of the strongest pieces of evidence yet that Dunkleosteus and modern cartilaginous fishes shared deeper similarities in jaw musculature and feeding mechanics. This muscle would have played a significant role in how the animal opened and closed its jaw and delivered powerful bites.

An Oddball Among Its Relatives

Even though Dunkleosteus is often used as the “default” example of an arthrodire, the study found that it was actually highly unusual for its group. Most arthrodires had true teeth, but Dunkleosteus and its closest relatives completely lost their teeth, replacing them with self-sharpening bone blades. These blades evolved separately in multiple arthrodire groups, meaning the trait was part of repeated, independent evolutionary experimentation in feeding strategies.

Understanding the New Evolutionary Context

The updated anatomical interpretation places Dunkleosteus more accurately within the broader arthrodire family tree. It turns out the species was part of a specialized lineage that evolved increasingly complex adaptations for hunting large prey. These adaptations—such as the bone blades, reinforced joints, and specialized muscles—suggest that Dunkleosteus was not simply a generalist predator but a highly adapted macropredator capable of biting chunks out of large animals.

This differs significantly from earlier ideas that treated arthrodires as relatively primitive or uniform. Instead, this study shows the group included a wide variety of ecological roles, body types, and feeding behaviors.

The bone-blade specialization, in particular, appears to have evolved multiple times within arthrodires, indicating strong evolutionary pressure toward powerful biting strategies. Dunkleosteus represents one of the most extreme versions of this trend.

What This Means for How Dunkleosteus Fed

This reassessment also challenges some high-profile biomechanical models from the past few decades. For example, older research suggested that Dunkleosteus used suction feeding, rapidly opening its jaws to pull prey inward. However, that model was based on outdated assumptions about muscle attachments and skull structure.

With the new findings, researchers now argue that suction feeding is unlikely. Instead, Dunkleosteus probably relied on:

- Fast, wide opening of the jaw

- Powerful closing forces delivered by specialized muscles

- Rigid, well-supported jaw joints

- Bone-blade slicing action for tearing large prey

This would have made Dunkleosteus comparable not to suction-feeding fishes but to large modern predators that rely on ram-feeding—actively lunging at prey and taking bites out of it.

Why Ohio Preserved So Many Dunkleosteus Fossils

Dunkleosteus fossils are found worldwide, but Cleveland is the hotspot. During the Devonian period, the region was covered by a shallow sea with conditions that favored fossil preservation. When these predators died, their armored skulls and torso plates sank into the soft sediment, eventually becoming entombed in what is now the Cleveland Shale.

Road projects, river erosion, and quarrying have exposed vast sections of this shale, providing paleontologists with an extraordinary supply of well-preserved material. This is why the Cleveland Museum of Natural History holds the most extensive Dunkleosteus collection in the world and why this new study could be conducted with such anatomical detail.

Additional Insights About Arthrodires and Early Jawed Fishes

Since this article is intended to give readers more knowledge beyond the immediate news, here are some useful background details:

- Arthrodires were among the earliest jawed vertebrates. Their evolution helped pave the way for modern fish lineages.

- Many arthrodires had highly flexible head and neck joints, allowing them to lift the entire head shield upward while opening the jaw—something not seen in modern fishes.

- Their bodies were mostly cartilaginous, which is why only the armored plates are commonly preserved.

- The Late Devonian period, sometimes called the “Age of Fishes,” saw explosive diversification in early vertebrates. Dunkleosteus was one of the apex predators during this evolutionary boom.

Understanding creatures like Dunkleosteus helps scientists trace how early jawed vertebrates evolved into the massive variety of species living today, including sharks, bony fishes, and eventually terrestrial vertebrates.

Why Even Famous Fossils Still Hold Secrets

This research is an example of how revisiting well-known fossils with modern techniques and updated anatomical knowledge can lead to completely new insights. Dunkleosteus has been a staple of paleontology for more than a century, yet it took until now to properly understand basic aspects of its skull, muscles, and feeding behavior.

The findings highlight how scientific knowledge evolves, even for iconic species, and why museums and fossil collections remain invaluable resources.

Research Paper:

Functional Anatomy, Jaw Mechanisms, and Feeding Behavior of Dunkleosteus terrelli

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.70075