Monk Parakeets Reveal How New Friendships Really Form in the Animal World

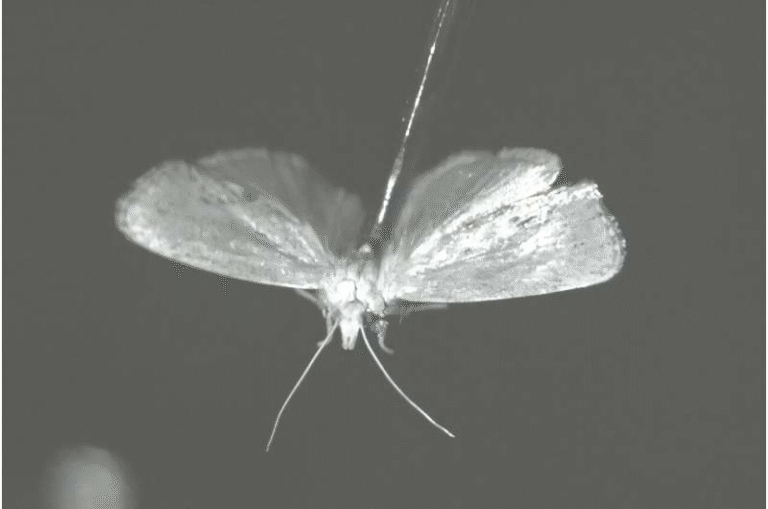

Researchers from the University of Cincinnati have uncovered how monk parakeets carefully form new social bonds, and their findings show a surprisingly methodical process that mirrors how many humans approach unfamiliar people. The study, published in Biology Letters, provides a close look at the earliest stages of relationship building—something rarely captured in animal research. What the team discovered is clear: these birds don’t rush into friendships. They gradually escalate their interactions, starting from safe, low-risk behaviors and moving toward more intimate acts only when trust is established.

The project was led by Claire O’Connell, a doctoral researcher who worked with co-authors Elizabeth Hobson, Annemarie van der Marel, and Gerald Carter from Princeton University. Their goal was to document how unfamiliar parakeets decide whether to build a relationship with a stranger. While parrots are generally known for forming strong pair bonds—often with one or two close partners—this research focused on how those relationships actually begin.

To investigate this, the team gathered groups of wild-caught monk parakeets and placed them into a large flight pen. The birds came from different original groups, which meant that many of them were complete strangers to one another. The setup allowed scientists to study first encounters with precise behavioral detail. Each bird was marked using colored dye, ensuring they could track every individual’s interactions over the nearly month-long observation period.

Over 22 days, researchers closely monitored more than 179 two-bird relationships. The behavior patterns they recorded fell into clear categories: low-cost behaviors, moderate-cost behaviors, and high-cost behaviors. Low-cost actions involved things like approaching another bird and sharing space without touching—simple proximity. Moderate-cost behaviors included shoulder-to-shoulder perching, beak touching, and preening, which require more trust and involve direct physical contact. High-cost behaviors carried the most investment and risk: sharing food (called allofeeding) and mating.

The findings showed a consistent pattern. When two birds were strangers, they began with the safest behavior—being near each other—but kept a cautious distance. Only after repeated non-contact proximity did they escalate toward grooming or gentle physical interactions. This gradual shift was far less common between birds that already recognized one another. In other words, familiarity eliminated the need for testing. Strangers, however, moved step by step, as if gauging whether the other bird would accept them or react aggressively.

The study notes that early interactions can be risky. Birds that try to preen another may be met with quarreling, a low-level aggressive response that signals discomfort. While not usually dangerous, this kind of pushback can deter further attempts. And if a newcomer pushes too far too quickly, reactions can escalate into behaviors that cause injury. This risk explains why a cautious, incremental approach makes evolutionary sense.

The researchers describe this pattern as testing the waters—a gradual escalation of friendliness that helps reduce the danger of interacting with unfamiliar individuals. This framework was previously documented in vampire bats, which also escalate from grooming to more cooperative acts like food sharing. Observing a similar model in monk parakeets suggests the strategy may be widespread among social animals.

One reason this study is notable is that early-stage relationship building is extremely hard to capture in the wild. Animals typically form bonds outside the view of observers, so scientists often only see the established partnership, not the initial negotiation. By bringing unfamiliar birds together in a controlled environment, the UC team had a rare chance to watch the process unfold from the very first moment.

The results also highlight how important strong bonds are for parrots. Monk parakeets, like many parrot species, often form lifelong partnerships. These relationships offer benefits such as reduced stress, reliable grooming partners, and higher reproductive success. But developing them requires navigating risk, trust, and compatibility—much like human friendships.

The research team points out that the behavior they observed feels intuitive. Humans, too, rarely leap into close friendship with someone immediately. Most people start with small interactions, gauge whether the other person is receptive, and slowly build up to deeper levels of connection. The parallels between animals and people make the parakeets’ strategy not just scientifically interesting but personally relatable.

Beyond the main findings, the study contributes useful knowledge about parrot social cognition. Monk parakeets are known for living in noisy, complex social groups and for building large communal nests. Their social world demands flexibility, awareness, and the ability to assess others quickly and accurately. Testing-the-waters strategies may be part of how they maintain stability in such densely interactive environments.

These results may also prompt further research into how widespread this strategy is. While documented clearly in vampire bats and now monk parakeets, the authors suspect that many other social species—especially those with long lifespans or complex group structures—might rely on similar gradual escalation when forming new relationships. Understanding this could shape how scientists interpret social bonding, cooperation, and group living across the animal kingdom.

Below are some additional sections that expand on the topic for readers who may want to explore further.

More About Monk Parakeets

Monk parakeets (also known as Quaker parrots) are small, bright green parrots native to South America. They are one of the few parrot species that build intricate communal stick nests rather than nesting in tree cavities. These nests can become enormous structures with multiple chambers, sometimes shared by dozens of birds.

They are highly social, vocal, and intelligent—traits that require sophisticated social strategies. Their ability to recognize individuals and form long-term partnerships makes them a valuable species for studying animal relationships. Monk parakeets have also become naturalized in several countries, including the United States, where feral populations live in cities such as Chicago, Miami, and New York.

Why Early Social Bonds Matter in Animal Behavior Studies

The earliest phases of social relationship formation are crucial yet rarely observed. These initial interactions determine who becomes allies, who becomes rivals, and how social networks take shape. For animals living in complex societies, early assessments can influence survival, access to resources, and reproductive opportunities. By observing monk parakeets from the start of interaction to fully developed social bonds, researchers gain insight into decision-making and risk calculation—skills often associated with more cognitively complex animals.

How This Research Connects to Broader Animal Behavior Patterns

Animal friendships are more common than people realize. Many species—including primates, dolphins, elephants, bats, and birds—form stable, meaningful relationships. These bonds impact emotional well-being, cooperation, and group success. The discovery that monk parakeets use a structured approach when meeting strangers reinforces the idea that social intelligence is a driving force in animal evolution. Testing the waters may be a shared strategy used by multiple species that depend on cooperation but must also avoid conflict.

Link to the Research Paper

Monk parakeets “test the waters” when forming new relationships – Biology Letters