Why Scientists Say Many Land Animals Eventually Returned to Water

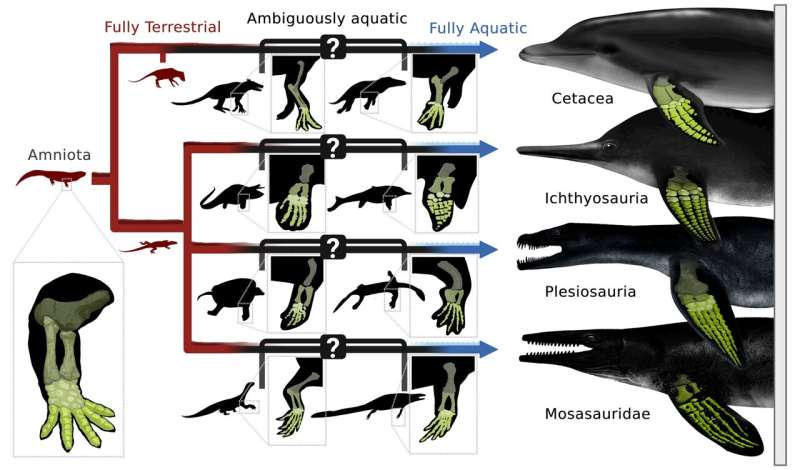

A new study from Yale University takes a deep and data-heavy look at a fascinating evolutionary pattern: the repeated return of land-dwelling animals back into aquatic environments. We usually picture evolution as a one-way journey from ocean to land, but dozens of reptile and mammal groups actually made the reverse trip over millions of years. This latest research offers one of the clearest explanations yet for when these returns happened, how they unfolded, and which species became fully committed to life in the water.

The work was carried out by researchers at Yale and several partner institutions and published in Current Biology. It uses an unusually large dataset, a blend of modern computational methods, and even techniques adapted from World War II radar statistics to understand the evolution of aquatic habits in extinct species.

A Massive Dataset Built From Fossils Around the World

The research team examined hundreds of fossil specimens from the Yale Peabody Museum and dozens of other museums across the globe. In total, they gathered more than 11,000 limb measurements, along with new photographs and CT scans. This scale matters because limb proportions often hold clues about whether an animal walked on land, paddled at the surface, or swam like a fully aquatic predator.

Instead of relying on a handful of traits—something paleontologists have traditionally done—the team built a broad quantitative dataset. They combined classic paleontology with machine-learning models trained on modern species, allowing them to statistically infer the likely behaviors and soft-tissue features of extinct animals whose muscles, skin, and webbing never fossilized.

Their approach helps cut down on researcher bias. For decades, paleontologists have disagreed about whether certain extinct animals were fully aquatic or just occasional swimmers because different features in the same skeleton often point in conflicting directions. By letting the data produce predictions, the researchers aimed for a more objective reconstruction.

Machine Learning Brings New Clarity to Old Debates

A major challenge in studying extinct animals is that bones rarely provide a full picture. But the team found that forelimb proportions, especially relative hand length, were highly predictive of whether an animal likely had soft-tissue flippers or spent substantial time underwater.

The machine-learning models achieved over 90% accuracy when predicting whether a species was highly aquatic or fully aquatic. This is significant because many traditional “bone-based clues” about webbing or swimming—such as flattened claws, widened phalanges, or symmetrical hand shapes—turned out to be unreliable across broad evolutionary groups.

This finding is important: many papers in the past have confidently claimed that certain dinosaurs or early reptiles had webbed feet, even though the correlation between those bone shapes and actual webbing was weak. The new research warns against assuming too much from individual features.

To enhance accuracy, the team even incorporated a statistical method originally developed in the 1940s to identify whether radar blips represented enemy aircraft. In this study, the technique helped calculate the probability that an extinct animal had limbs modified for swimming. It’s a striking example of how ideas from completely different fields can find new purpose in evolutionary biology.

What the Study Says About Spinosaurus and Other Controversial Species

One of the most high-profile debates this research addresses is the lifestyle of Spinosaurus, the enormous, sail-backed dinosaur that lived about 113 to 94 million years ago in what is now northern Africa. For years, scientists have argued about whether Spinosaurus was a shoreline wader or a deep-water hunter.

Using their new models, the researchers found strong evidence that Spinosaurus had highly aquatic habits. Their predictions indicate the dinosaur likely spent the vast majority of its time submerged, supporting the idea that it actively hunted underwater—more like a seal or penguin than a heron standing in the shallows.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the study challenges assumptions about mesosaurs, small marine reptiles that lived 290 to 274 million years ago. Because they gave birth to live young, some scientists argued they must have been fully aquatic. But the limb data suggests otherwise: mesosaurs probably had a semi-terrestrial lifestyle, spending a lot of time on land similar to modern alligators or the platypus. In short, they were not the truly marine reptiles some researchers imagined.

The team also concluded that all Paleozoic marine reptiles—every reptile living in marine environments before the dinosaurs existed—likely returned to land regularly. None show the limb proportions associated with full aquatic specialization. At most, they seem to have lived amphibious lives.

This helps reshape our understanding of early marine reptile evolution, suggesting that full ocean commitment in reptiles happened later and in a more limited set of lineages than previously believed.

Why Aquatic Adaptation Keeps Evolving Again and Again

The study highlights how many major animal groups independently evolved aquatic lifestyles long after their ancestors had moved onto land. This is classic convergent evolution, where unrelated species evolve similar features because they face similar environmental pressures.

Across these groups, patterns repeat:

- limbs evolve into paddles or flippers

- limb bones shorten or shift in proportion

- bodies streamline for swimming

- soft-tissue structures appear that don’t fossilize but can be predicted statistically

These repeated patterns underscore how environments shape anatomy. Whenever land animals explored aquatic habitats—whether for food, safety, or competition—the same kinds of solutions evolved again and again.

What This Study Adds to Our Understanding of Evolution

Beyond its specific findings, the study introduces a method that could be applied to many other evolutionary mysteries. Because it predicts soft-tissue traits using only bones, it could help scientists understand:

- when early human ancestors began walking on two legs

- how flight gradually evolved in dinosaur ancestors of birds

- which extinct species developed specialized locomotion patterns

In paleontology, bones are nearly always all we have. Soft tissue rarely fossilizes, and behavior never does. By offering a way to reconstruct habits without subjective guesswork, the method opens the door to re-examining many long-debated species.

The researchers emphasize that the goal is not to replace expert interpretation, but to give paleontologists a stronger foundation. With thousands of measurements and a model trained on modern animals, the ecological inferences become more evidence-driven.

Additional Background: Why Returning to Water Happens So Often

To give additional context, it’s worth noting that many iconic animals alive today evolved from terrestrial ancestors that later returned to water. Some well-known examples include:

- Whales and dolphins, which descended from four-legged land mammals

- Seals and sea lions, which still retain some terrestrial traits

- Sea turtles, which evolved flippers but must come ashore to lay eggs

- Penguins, evolved from flying birds into expert underwater hunters

Returning to the water provides access to abundant food, fewer land-based predators, and vast new ecological niches. But it also requires major anatomical transformations. This is why convergent evolution is so prominent in aquatic animals—very different lineages end up developing similar solutions, like flippers, streamlined bodies, or specialized bone structures.

Additional Background: Why Limb Proportions Matter in Evolution

Limb proportions tell scientists a lot about how an animal moved. For example:

- Long, flexible fingers often suggest grasping or climbing.

- Short, stiffened limbs suggest paddling.

- Lengthened hands or forearms can indicate flipper-like motion.

- Certain ratios between limb segments predict whether an animal used its limbs underwater or on land.

Because these proportions correlate so strongly with locomotion, they remain one of the most reliable indicators of ecological habits—even millions of years after soft tissue has vanished.

This is why the new study focused so heavily on measurements. The more data points collected, the more confidently scientists can run comparisons between extinct species and living animals whose behavior we already know.

Research Paper

Limb Proportions Predict Aquatic Habits and Soft-Tissue Flippers in Extinct Amniotes

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(25)01449-6