A Newly Discovered Form of Mitochondrial DNA Damage Could Change How We Understand Cellular Stress

A team of researchers led by the University of California, Riverside has identified a completely new type of DNA damage inside our mitochondria — the tiny, energy-producing compartments within nearly all our cells. This discovery shines a light on how our bodies might sense and respond to stress at the molecular level, and it could have implications for diseases ranging from cancer to diabetes.

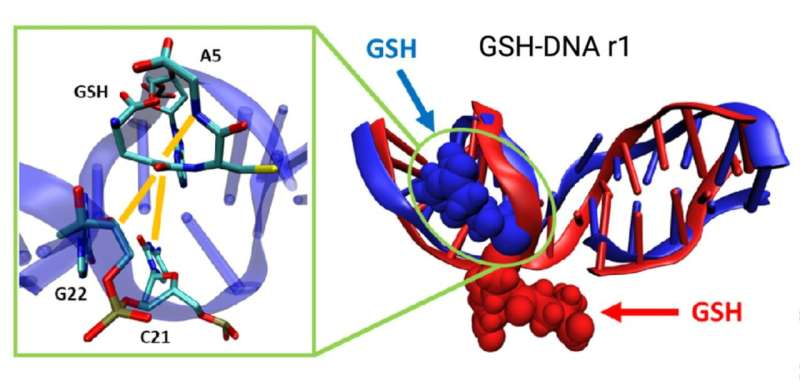

The newly identified culprit is a type of chemical tag known as a glutathionylated DNA adduct, or GSH-DNA adduct. An adduct forms when a chemical attaches itself directly to DNA, creating a bulky modification that can interfere with normal DNA function. What makes this finding especially noteworthy is that these GSH-DNA adducts show up far more often in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) than in the DNA stored in the cell’s nucleus.

Mitochondria carry their own genetic material—just 37 genes compared to the tens of thousands found in nuclear DNA. This mtDNA is circular, inherited only from the mother, and represents just 1–5% of total cellular DNA. Even though it is so limited, it plays an essential role in energy production and cellular communication. Because of its structure and location, mitochondrial DNA has long been known to be more vulnerable to damage, but scientists did not fully understand how certain kinds of chemical damage occurred. This new research uncovers one of those missing pieces.

Why Mitochondrial DNA Is So Vulnerable

The study found that GSH-DNA adducts accumulate up to 80 times more in mitochondrial DNA than in nuclear DNA during laboratory experiments using human cells. That is a striking difference and supports the idea that mtDNA faces harsher chemical conditions and has weaker repair systems.

Unlike nuclear DNA, which benefits from robust repair mechanisms, mtDNA has less efficient ways to fix damage. Each mitochondrion contains multiple copies of mtDNA, which offers some protection, but the repair tools it possesses are not as strong. This imbalance may allow unusual or persistent forms of damage, like GSH-DNA adducts, to build up over time.

What These Adducts Are Doing to the Cell

When these sticky adducts accumulate, they create several notable effects inside mitochondria. The researchers observed:

- Reduced levels of proteins required for energy production, especially components of mitochondrial Complex I.

- Increased levels of proteins involved in stress response and mitochondrial repair, indicating that cells recognize this damage and try to counteract it.

These changes suggest a link between GSH-DNA adducts and overall mitochondrial health. A decrease in energy-related proteins could impair how well mitochondria function, while an increase in repair-related proteins shows that cells respond dynamically to this damage.

The research team also explored the structural impact of these adducts through advanced computer simulations. The simulations revealed that GSH-DNA adducts make mtDNA more rigid and less flexible. This change in flexibility could be the cell’s way of marking damaged DNA for disposal, preventing it from being copied or used. If mitochondria can identify rigid, chemically altered pieces of mtDNA, they may be able to remove them before they contribute to further problems.

Why This Matters for Human Health

Damaged mitochondrial DNA is not just a local problem inside the mitochondria — it can send distress signals throughout the cell and even the immune system. When mtDNA becomes damaged, it can escape into the rest of the cell or into the bloodstream, where the immune system may mistake it for a threat. This can spark inflammation, an important factor in several chronic conditions.

Research has already linked dysfunctional mitochondria and inflammation to diseases like neurodegeneration, metabolic disorders, and diabetes. The discovery of this new type of mtDNA modification provides scientists with a new direction for exploring how mitochondrial stress contributes to disease.

Because GSH-DNA adducts represent a previously unknown form of damage, they might eventually become biomarkers—molecular signs that help diagnose or predict mitochondrial-related illnesses. Understanding how these adducts form and how cells attempt to repair them may also open the door to future treatments that improve mitochondrial function.

What Creates These Adducts?

GSH-DNA adducts form when glutathione (GSH), a key antioxidant in cells, attaches to DNA. Glutathione normally protects cells from oxidative stress, but under certain conditions it can react with damaged or chemically altered DNA bases. The results of this study indicate that these adducts tend to accumulate specifically in mitochondrial DNA.

In the mitochondria, chemicals known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) are naturally produced during energy generation. These reactive molecules can create DNA lesions, generating situations where glutathione might attach to mtDNA. If the repair systems in mitochondria cannot keep up, these GSH-DNA adducts may start to build up.

How Cells Regulate These Adducts

The study also confirmed that two major enzymes help manage these sticky modifications:

- AP endonuclease 1 (APE1)

- Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1)

Both enzymes are known for roles in DNA repair in the nucleus, but this research shows they also contribute to handling GSH-DNA adducts in mitochondria. Their involvement suggests that mitochondria do have some capacity to recognize and manage this damage, though not as efficiently as nuclear DNA repair pathways.

What This Discovery Adds to Our Understanding of Mitochondria

Mitochondrial biology has always been a fascinating area of study because mitochondria operate somewhat independently from the rest of the cell. They have their own DNA, their own protein-making machinery, and their own rules for replication and repair. This discovery adds another layer to that unique biology.

Here are a few broader points to consider:

- Mitochondria generate the majority of the cell’s energy, so damage to mtDNA can directly affect energy levels.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction is linked to aging, since mitochondrial damage accumulates over a lifetime.

- Many neurological diseases, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, have strong mitochondrial components.

- Mitochondria are central to apoptosis (programmed cell death), meaning that mtDNA damage could influence cell survival or death.

The discovery of a new, structurally distinct form of mtDNA damage underscores how much remains to be learned about these vital structures. It also highlights the importance of mitochondrial quality control—cells rely on healthy mitochondria not just for energy, but also for maintaining internal balance.

Additional Background: Why Mitochondrial DNA Damage Is So Important

Mitochondrial DNA damage is more than a biochemical curiosity. Because mitochondria are inherited only from the mother, any inherited defects in mtDNA pass through the maternal line. Certain mitochondrial diseases are caused directly by mtDNA mutations, and because mtDNA repair is limited, damage can accumulate rapidly in tissues with high energy demand, like the brain, heart, and muscles.

Unlike nuclear DNA, mtDNA is not protected by histones—the proteins that package and shield nuclear DNA. This lack of protection makes it more exposed to reactive molecules that can cause damage. The discovery of GSH-DNA adducts helps explain one of the ways this damage might occur and why it accumulates so heavily in mitochondrial DNA.

The Bigger Picture for Future Research

This study opens the door to several new research questions:

- Under what conditions do GSH-DNA adducts form most frequently?

- Do they accumulate with age or in specific diseases?

- Can enhancing mitochondrial repair systems reduce or remove these adducts?

- Could measuring GSH-DNA adduct levels become a diagnostic tool?

As researchers explore these ideas, we may one day see new therapies targeting mitochondrial health at the DNA level.

Research Paper:

Glutathionylated DNA adducts accumulate in mitochondrial DNA and are regulated by AP endonuclease 1 and tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2509312122