Multicellular Cyanobacteria Show Distinct Day-Night Gene Activity in Natural Light Cycles

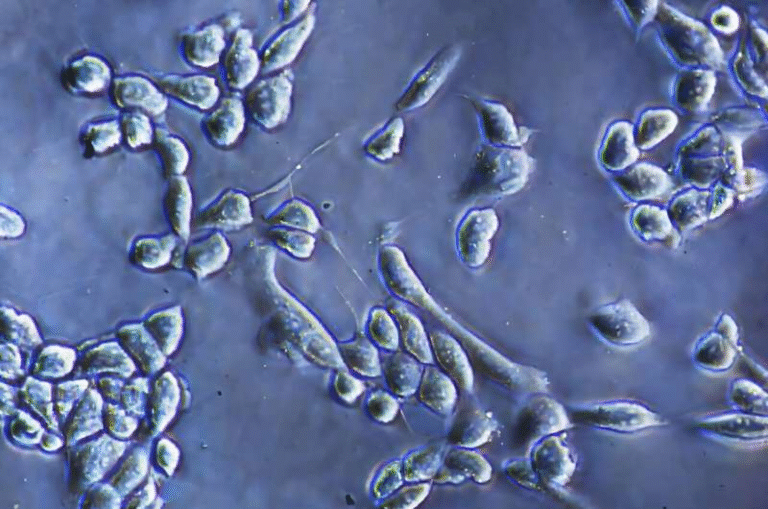

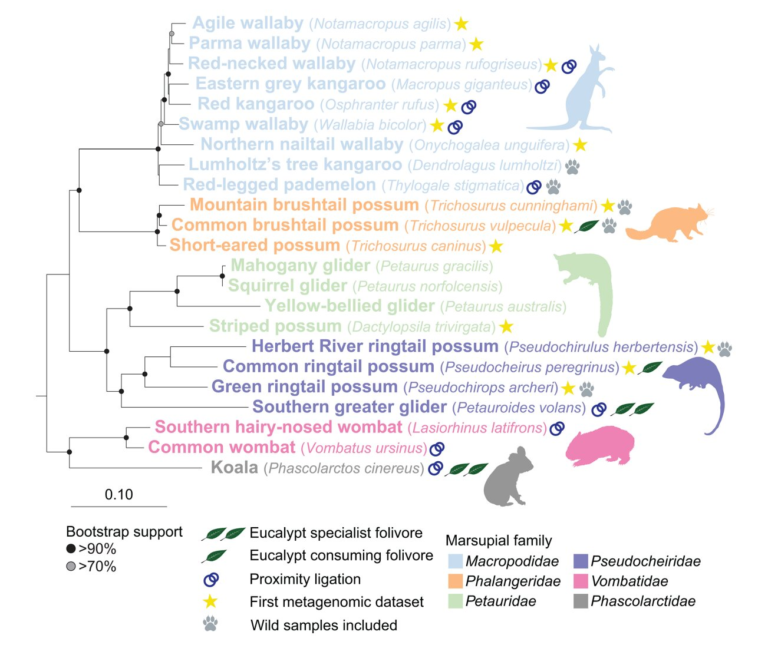

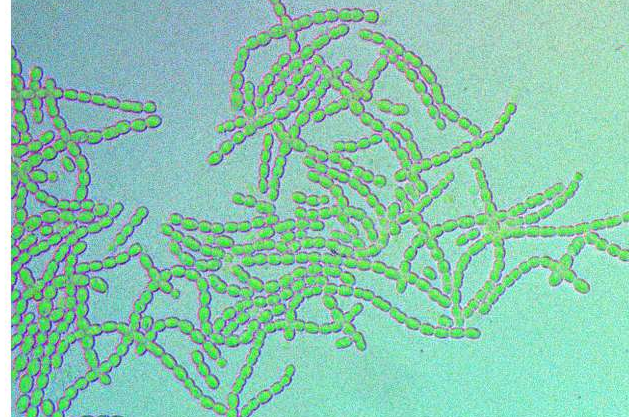

Multicellular cyanobacteria are tiny but powerful contributors to ecosystems across the planet, and a new study has revealed just how dynamic their daily biological routines are. Researchers at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) have shown that these microorganisms dramatically switch their genetic activity between day and night when they experience natural light–dark cycles. The study focuses on Nostoc punctiforme, a filament-forming species found in diverse habitats, and it uncovers details about how these organisms divide their tasks across a 24-hour period.

The team’s work challenges long-held assumptions in microbial research, especially because most earlier studies grew cyanobacteria under constant illumination. Continuous light is convenient in the lab because it speeds up growth, but it also hides how these organisms coordinate metabolism, repair, and genome reshuffling in nature. The new study—conducted under day-night conditions—reveals patterns that simply do not appear under unchanging lab lighting.

In the natural-light experiments, researchers tracked gene expression throughout the entire diel cycle. During the day, the cells emphasize metabolism, tightly aligning photosynthesis with carbon assimilation to fuel cell division. Under night conditions, the same cells shift their attention toward genome repair, DNA recombination, and the activation of mobile genetic elements that reorganize segments of their DNA. This alternating pattern highlights how these microorganisms optimize energy use and protect their genetic integrity in rhythm with sunlight.

One major finding involves diversity-generating retroelements, specialized genes that introduce rapid, targeted mutations at certain spots in the genome. These retroelements appear across many cyanobacterial species, particularly the multicellular ones, and the study confirmed that they remain active throughout the 24-hour cycle. Their constant activity hints at an evolutionary strategy that encourages flexible, fast adaptation — a useful trait for organisms living in environments where sunlight, nutrients, and other conditions can shift unpredictably.

The researchers were also surprised to find mobile genetic elements, carried by phages, moving in and out of the N. punctiforme genome. These transposons were especially active at night. Their movement suggests that cyanobacteria maintain a dynamic internal genome architecture and may play a role in how genes spread across microbial communities. This discovery raises broader ecological questions: if cyanobacteria are exchanging genetic material with viruses, what exactly are they passing on to other microorganisms? Are these exchanges beneficial, harmful, or context-dependent?

To understand why these gene-shifting abilities matter, it helps to appreciate the ecological role of multicellular cyanobacteria. These organisms are primary producers, forming the base layer of energy flow in many ecosystems. They live in soils, freshwater, oceans, and even in close association with plants. Their ability to perform photosynthesis places them at the foundation of nutrient and carbon cycles globally. However, some of their relatives can also form harmful algal blooms that release toxins, including neurotoxins, which can threaten wildlife and human health. Learning how their genomes behave under real environmental conditions could help scientists better predict when and how these blooms form.

Another important detail from the research relates to the size of the genome itself. Multicellular cyanobacteria like N. punctiforme often have genomes around 8 million DNA letters long, much larger than those of many single-celled counterparts, which average around 3 million letters. A larger genome allows for extra complexity—more regulatory genes, more metabolic options, and more flexible responses. This size difference likely helps multicellular cyanobacteria coordinate the specialized cells they use to survive stress, fix nitrogen, or disperse to new locations.

Despite the long history of cyanobacteria research, relatively little was known about the circadian rhythms of multicellular species. Most existing studies were centered on single-celled varieties, and they often revealed predictable patterns tied to light cues. The new study shows that multicellular cyanobacteria have their own rhythms, some of which appear to involve new gene families not known from single-celled organisms. These genes may serve clock-like roles even though their exact functions remain unknown. As researchers continue to explore them, they may uncover entirely new biological mechanisms that help multicellular microbes coordinate their internal timing.

By highlighting the differences between lab-grown and naturally behaving cyanobacteria, the researchers emphasize the importance of studying microorganisms under realistic conditions. Light cycles, temperature fluctuations, and ecological interactions can dramatically reshape gene expression profiles. Without these variables, laboratory studies may be missing major pieces of the puzzle.

More broadly, the results open the door to deeper questions about the role of cyanobacteria in microbial ecosystems. Their dynamic genetic elements might influence not only their own evolution but also the genomes of surrounding microbes. Because cyanobacteria are abundant and widespread—occupying almost any habitat where sunlight reaches—they serve as major hubs of microbial interaction. If they regularly shuffle genes or participate in phage-mediated exchanges, the ripple effects could reach far beyond a single species.

Understanding this genetic dynamism also offers insights into how cyanobacteria adapt to environmental stress. Natural environments expose microbes to rapidly changing variables such as light intensity, nutrient availability, and temperature. The ability to modify parts of the genome quickly may be a crucial mechanism allowing these organisms to withstand such fluctuations. Future studies may explore whether genome-shifting activity increases under stress or contributes to symbiotic relationships with plants.

Beyond the specifics of this research, it’s worth stepping back to consider why cyanobacteria as a group are so important. They are among the oldest known organisms on Earth and played a central role in shaping the planet’s atmosphere through oxygenic photosynthesis. Today, they remain essential contributors to global carbon and nitrogen cycles. Multicellular cyanobacteria, in particular, stand out for their specialized cell types. For example, they can form heterocysts to fix atmospheric nitrogen, hormogonia for dispersal, and akinetes to survive harsh conditions. These specialized cells require precise genetic coordination — making the discovery of day-night gene switching even more significant.

Cyanobacteria also influence modern technological fields. They are studied for biofuel production, bioremediation, nitrogen fixation technologies, and even synthetic biology applications. Understanding how their gene regulation responds to environmental cues could improve bioengineering strategies. If scientists can mimic or manipulate these natural gene-expression rhythms, it may become possible to optimize cyanobacteria for sustainable energy or agricultural systems.

While the study answers many questions about daily gene-expression patterns, it also raises new ones. For example, do all multicellular cyanobacteria follow similar day-night genetic routines? How do environmental stresses like UV exposure or nutrient scarcity interact with these rhythms? And how do phage-associated mobile elements shape long-term evolution? These unanswered questions show that even after decades of research, cyanobacteria still hold many secrets.

The new findings represent a major step forward in understanding the full complexity of microbial life. By looking at gene expression over natural light cycles, scientists gained insights impossible to see under constant lighting. The discovery of active retroelements, nighttime transposon movement, and new potential circadian components adds layers of nuance to how multicellular cyanobacteria organize their daily lives. As more studies follow this natural-conditions approach, our picture of microbial physiology will likely become far more accurate and far more fascinating.

Research paper:

https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.03779-24