Cabernet Sauvignon Still Holds a 400-Year-Old Molecular Memory of Its Ancestry

Cabernet Sauvignon may be one of the world’s most familiar wine grapes, but new research shows it still carries a surprisingly enduring molecular memory of where it came from. Scientists at the University of California, Davis have revealed that this grape, created in the 17th century through a natural cross between Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc, still retains stable epigenetic signatures inherited from its ancestors. These findings highlight how long-lived, clonally propagated crops can preserve molecular traits for centuries and may reshape how viticulturists think about grape resilience, quality, and breeding in the future.

A Grape That Has Been Cloned for Centuries

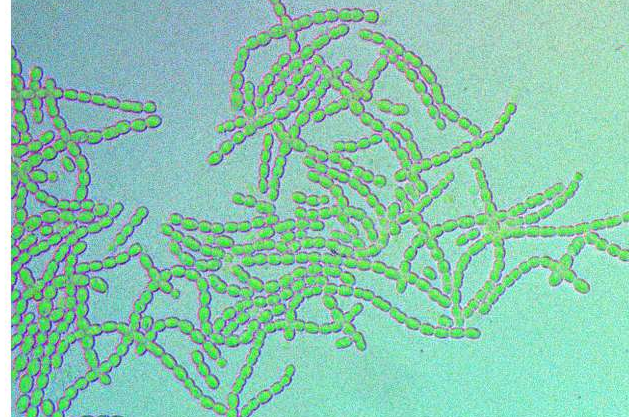

Unlike annual crops such as wheat or corn, wine grapes are propagated through cuttings, a form of cloning. Every Cabernet Sauvignon vine grown today—from Napa to Bordeaux to vineyards across the Southern Hemisphere—descends from that original hybrid plant created roughly 400 years ago. This means modern vines are genetically nearly identical to the first Cabernet Sauvignon vine.

Because these vines are copied rather than sexually reproduced, scientists have long wondered what happens to epigenetic marks—chemical tags on DNA that control how genes turn on and off. These marks do not change the DNA sequence but have a major influence on plant traits, including stress tolerance, fruit quality, and overall development. The central question has been whether these marks disappear over centuries or whether they persist across generations of clones.

The new UC Davis study provides a clear answer: many of these epigenetic signatures remain remarkably stable, even after hundreds of years.

Understanding What Was Actually Discovered

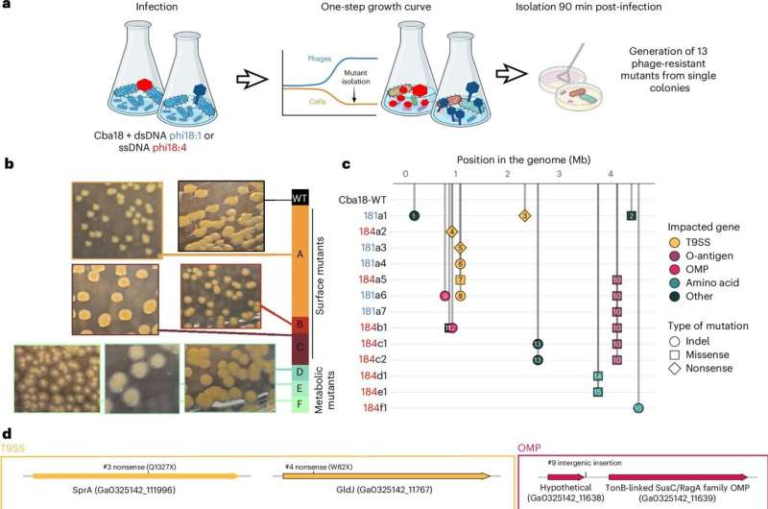

The research team used state-of-the-art long-read genome sequencing to assemble detailed, phased genome maps for Cabernet Sauvignon and its parent grapes, Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. These phased maps allow scientists to distinguish which genetic and epigenetic information came from which parent—something traditional genome references cannot do as accurately.

Multiple clones from each cultivar were analyzed, and researchers created a phased sequence graph, a sophisticated model that captures subtle variations in both DNA sequence and epigenetic methylation patterns. Using this framework, the team tracked how epigenetic marks, especially DNA methylation, are passed down along with genetic material.

One of the standout findings is the stability of mCG methylation, the most abundant type of DNA methylation in plants. These methylated cytosines typically suppress gene expression. However, some gene categories, such as gbM genes, behave differently, illustrating how methylation patterns influence functional gene activity.

Despite minor differences between individual vines—expected due to environmental influences and local growing conditions—the core epigenetic patterns inherited from the parent species remain intact. In other words, Cabernet Sauvignon has maintained a consistent, long-lasting molecular memory that reflects its original ancestry.

Why Epigenetic Memory Matters for Viticulture

This discovery is especially relevant as vineyards worldwide face rapidly changing climate conditions. If certain epigenetic responses to heat, drought, or pathogen stress are proven to be stable over long periods, researchers may be able to use these traits in breeding and vineyard management.

One potential future application is the deliberate induction of beneficial epigenetic marks. For example, if exposing vines to controlled stress produces favorable, long-lasting epigenetic changes, viticulturists could select vines that retain these marks. This would create plants with enhanced resilience without altering their genetic identity—a key advantage for highly valued varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, where consistency and tradition matter.

Because the study demonstrates that epigenetic marks can persist for centuries, it opens the door to long-term epigenetic breeding strategies, something previously uncertain in perennial crops.

A Historic Connection for UC Davis

This work also ties back to an earlier milestone in grape genetics. In 1997, UC Davis professor Carole Meredith first identified the parentage of Cabernet Sauvignon, confirming it as the offspring of Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. Nearly thirty years later, Dario Cantù’s research group has shown that the grape continues to exhibit molecular reminders of that historical pairing.

It is a full-circle moment: one UC Davis discovery uncovered the grape’s genetic roots; another now shows that those roots remain deeply embedded at the molecular level.

How Clonal Plants Retain Their Identity

Clonal propagation offers a unique window into plant biology. Because no new genetic recombination occurs, any changes over time are primarily due to:

- Random mutations

- Environmental influences on gene expression

- Epigenetic modifications

Epigenetics becomes particularly important because it helps explain how genetically identical vines can still differ in subtle ways depending on their growing environment, age, or stress exposure. Yet, the fact that major inherited epigenetic patterns remain intact after hundreds of years shows that clonal crops may be more stable than previously assumed.

This stability is beneficial for wine production: it helps maintain flavor profiles, crop quality, and predictable performance in vineyards across the world. Consistency is one of the reasons classic grape varieties persist for centuries, and this new research suggests epigenetic inheritance plays a major role in that longevity.

Expanding the Benefits Beyond Grapes

Although the study focuses on Cabernet Sauvignon, the analytical framework it introduces can be applied to many other perennial crops that rely on clonal propagation. This includes:

- Apples

- Olives

- Pears

- Stone fruits

- Berries

- Coffee

Understanding how epigenetic marks behave over long lifespans could guide breeding programs for improved fruit quality, disease resistance, and climate resilience across these crops.

What Epigenetics Means for Everyday Wine Lovers

For consumers, the takeaway is simple but fascinating: the Cabernet Sauvignon poured into a glass today is not just genetically linked to its 17th-century ancestor—it also retains molecular marks from those original parent grapes. This contributes to the grape’s reputation for consistency and quality, and it helps explain why classic wine varieties can remain stable and recognizable over centuries.

It also provides a scientific layer to the idea of tradition in winemaking. The grape does not just share a lineage; it carries a molecular memory of where it came from.

The Future of Wine Research

Going forward, researchers are likely to explore how stable epigenetic marks influence:

- Berry composition

- Yield

- Resistance to pathogens

- Adaptation to heat and water scarcity

- Expression of desirable winemaking traits

If scientists identify specific epigenetic markers linked to resilience or fruit quality, those markers could become new targets for vine selection, helping vineyards adapt to global challenges without losing varietal identity.

This study represents a major step toward understanding how grapes evolve—or remain stable—over centuries, and it highlights the power of modern genomics to unlock secrets hidden in some of agriculture’s oldest crops.

Research Paper:

Phased epigenomics and methylation inheritance in a historical Vitis vinifera hybrid — Genome Biology (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-025-03858-2