New Evidence Suggests Molecular Evolution Isn’t Neutral After All and Organisms Are Constantly Chasing Their Changing Environments

For decades, many evolutionary biologists have leaned on the Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution, a long-standing idea proposed in the 1960s. This theory argues that most genetic mutations that become permanent in a population—what scientists call fixations—are neither beneficial nor harmful. They’re essentially neutral, slipping into the genome because natural selection doesn’t notice them.

A new study from the University of Michigan, however, challenges this foundational assumption with detailed experimental data and a fresh theoretical model. Led by evolutionary biologist Jianzhi Zhang, the research team found that beneficial mutations are far more common than neutral theorists believed, but these helpful changes rarely become permanent due to rapidly shifting environments. As a result, evolution appears neutral even when the underlying process is anything but.

Below is a clear, detailed walk-through of what this new research discovered, how the scientists tested it, and why it may reshape how we think about molecular evolution.

The Core Finding: Beneficial Mutations Are Not as Rare as We Thought

The research team examined large deep mutational scanning datasets — experimental collections in which thousands of mutations are introduced into genes in organisms like yeast and E. coli. These datasets allowed the researchers to measure the fitness effects of thousands of single mutations and compare them directly to the wild-type versions.

Across these datasets, the team observed that more than 1% of mutations were beneficial, which is orders of magnitude higher than the Neutral Theory allows. According to classical evolutionary thought, beneficial mutations should be exceptionally rare, because harmful mutations get weeded out and beneficial ones occur only occasionally.

If beneficial mutations were truly this common, logic suggests they should fix frequently, causing rapid evolution at the molecular level. But scientists know that molecular evolution is generally slow, and most fixed mutations appear indistinguishable from neutral ones. This created a contradiction: why don’t these many beneficial mutations take over?

Why Beneficial Mutations Don’t Become Permanent

The team realized the typical assumption—that environments remain constant during evolution—is unrealistic. Natural environments change, sometimes unpredictably and quickly. A mutation that’s helpful in one environment may become harmful or neutral when the environment shifts.

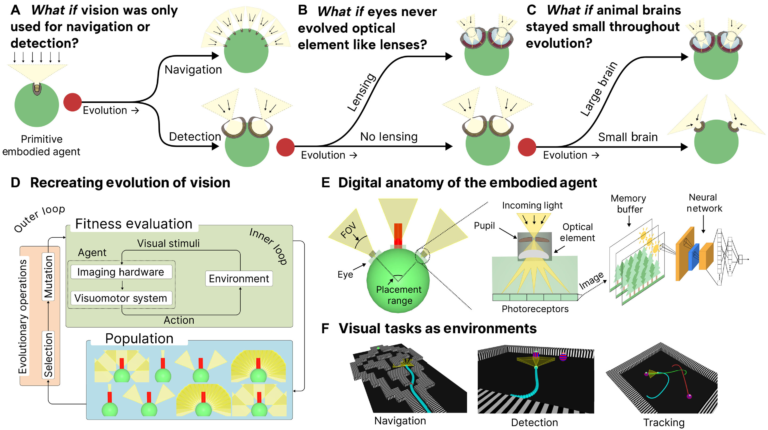

To explore this dynamic, Zhang’s team proposed a new model they call Adaptive Tracking with Antagonistic Pleiotropy. In simple terms:

- Populations are constantly trying to track their environment through new mutations.

- But many beneficial mutations come with trade-offs: what helps in environment A becomes harmful in environment B.

- Because environments change before many beneficial mutations can fully spread, these mutations never get fixed.

This means the process isn’t neutral—mutations genuinely affect fitness—but the outcome looks neutral because beneficial ones rarely stay long enough to dominate.

Experimental Proof: Testing Evolution in Constant vs. Changing Conditions

To test the idea directly, the team conducted a controlled experiment using yeast populations. They divided the yeast into two groups:

- Group 1: Evolved for 800 generations in a constant environment.

- Group 2: Evolved for 800 generations in 10 different environments, each one lasting 80 generations before switching.

The results were striking:

- In the constant environment, beneficial mutations appeared and had time to rise in frequency, increasing the population’s adaptation.

- In the changing environment, beneficial mutations still arose, but very few became fixed because each environmental change altered which mutations were advantageous.

In essence, the yeast in shifting environments were always adapting but never catching up, perfectly illustrating the adaptive tracking model.

What This Means for How We Understand Evolution

If beneficial mutations occur frequently, but environments shift before they can fix, then most long-term genetic changes will appear neutral, even though the underlying process is dynamically adaptive. This explains why molecular evolution seems slow and mostly neutral despite organisms constantly battling to match their environments.

This perspective carries implications beyond microbes:

- Humans, for example, have moved through many different environments over evolutionary time.

- Mutations that once helped our ancestors survive might be poorly suited to modern conditions.

- This could help explain why certain traits or genetic predispositions seem mismatched today.

Zhang emphasizes that no natural population is ever perfectly adapted to its current environment. Instead, organisms are perpetually on the move, trying to match conditions that shift faster than genes can fully adjust.

How the Study Fits Into the History of Evolutionary Thought

The Neutral Theory, introduced in the 1960s, revolutionized evolutionary biology by shifting focus from visible traits to molecular changes—mutations in DNA and proteins. At the time, scientists had just begun sequencing proteins and genes, opening a new window into evolutionary processes.

Under this theory:

- Most genetic changes fixed in populations are neutral.

- Beneficial mutations are so rare that they hardly contribute to long-term molecular evolution.

- The rate of molecular evolution mainly reflects random drift, not natural selection.

The new study doesn’t claim Neutral Theory was wrong in its observations—fixed mutations do often appear neutral. But it challenges the reason why they appear neutral, showing that frequent environmental fluctuations may hide underlying adaptive processes.

Additional Context: What Is Antagonistic Pleiotropy?

A key concept in the new model is antagonistic pleiotropy, which occurs when a single mutation has opposing effects depending on the environment or life stage.

Examples include:

- A mutation that boosts growth in one resource condition but weakens survival in another.

- A genetic change helpful in early life but harmful later (common in aging research).

In Zhang’s model, antagonistic pleiotropy explains why beneficial mutations rarely dominate: they can’t stay beneficial long enough in an unpredictable world.

Why the Study Focused on Yeast and E. coli

Deep mutational scanning is easiest to perform in unicellular organisms, where:

- Generations are short (hours rather than years).

- Populations are enormous.

- Mutations can be measured with precision.

The researcher acknowledges that more data is needed from multicellular species, where development, tissue differences, and longer lifespans complicate mutation effects.

Future research will test whether the findings extend to animals, plants, and ultimately, humans.

Where the Researchers Are Going Next

The team plans to investigate:

- Why organisms take so long to fully adapt even in constant environments.

- How mutation interactions (epistasis) modify adaptation over time.

- Whether similar patterns hold in complex species and natural ecosystems.

This research may reshape how evolutionary biologists think about mutation, adaptation, and long-term genomic change.

Research Reference

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025) – Adaptive tracking with antagonistic pleiotropy results in seemingly neutral molecular evolution

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-025-02887-1