How Cold-Water Algae Helped Marine Life Survive Earth’s Worst Mass Extinction

The Permian–Triassic extinction, often called the Great Dying, is known as the most catastrophic extinction event our planet has ever experienced. Around 252 million years ago, Earth lost about 81% of all marine species and a huge share of life on land. Global warming, collapsing food chains, oxygen-poor oceans, and massive environmental changes transformed the planet so severely that recovery took hundreds of thousands of years.

But recent research adds a fascinating new detail to this ancient crisis: cold, high-latitude oceans may have provided safe havens where certain algae flourished, keeping small pockets of marine life alive while the rest of the world’s seas were devastated.

This new study, published in AGU Advances, focuses on molecular fossils found in Arctic rocks—chemical traces left behind by organisms that lived shortly after the Great Dying. These traces show that certain phytoplankton not only survived the catastrophe but bloomed in the cooler waters of what is now Svalbard, Norway. These algae may have supported marine ecosystems during a time when warmer waters became nearly uninhabitable.

The Study Site and the Goal

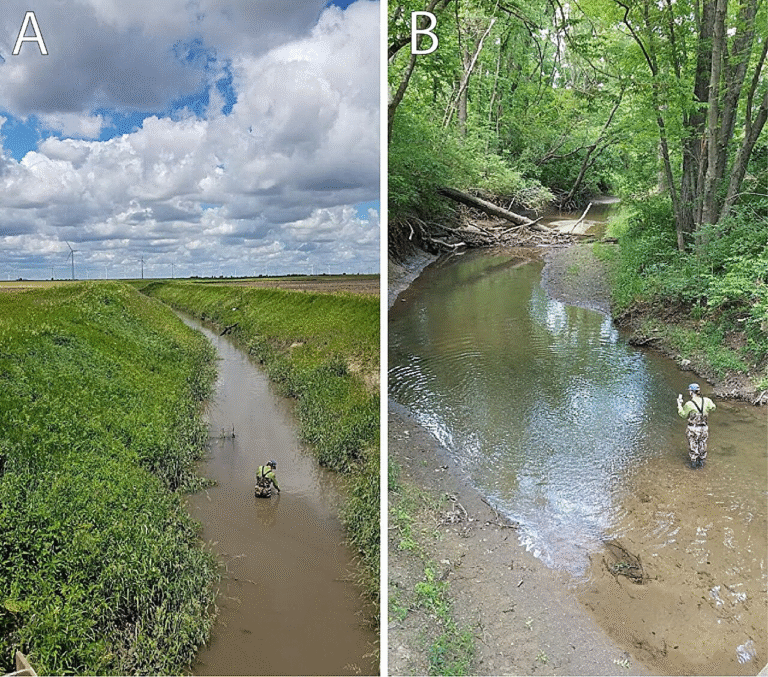

Scientists led by S. Z. Buchwald investigated rocks from the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, specifically from the Selmaneset section in western Svalbard. Today this region sits in the high Arctic, but even 252 million years ago, it was located in higher-latitude, cooler marine environments compared to much of the prehistoric world.

The research team collected 32 rock samples from geological layers formed before and after the extinction event. They compared these with samples from several warmer paleo-regions:

- Northern Italy

- Southern China

- Türkiye

All three belonged to the ancient Tethys Ocean, the warm-water ocean that existed long before the modern Indian and Mediterranean Seas.

Their goal was straightforward: look for specific organic biomarkers—chemical remnants of ancient organisms—to understand how marine ecosystems behaved during and after the Great Dying.

Which Biomarkers Did They Look For?

The team searched for two particular lipid-based molecular fossils:

- C33–n-alkylcyclohexane (C33–n-ACH)

- Phytanyl toluene

These molecules act like chemical fingerprints of ancient phytoplankton. If their concentrations rise or fall in sediment layers, scientists can infer how well certain types of algae were surviving or blooming at that time.

What the Scientists Found in Svalbard

The findings from Svalbard were unexpectedly dramatic.

Huge Spike in C33–n-ACH After the Extinction

In post-extinction layers from Svalbard, levels of C33–n-ACH were about 10 times higher than in the layers formed before the extinction.

This indicates a major increase in the organisms producing these molecules, likely a specific group of phytoplankton adapted to cooler waters.

Importantly, while pre-extinction samples were older and may have degraded more, the biomarker they studied is highly resistant to degradation. That means the spike isn’t just an artifact—it reflects a real ecological change.

Phytanyl Toluene Appears Only After the Extinction

Before the extinction, Svalbard rocks contained almost no phytanyl toluene. Afterward, its levels jumped significantly.

This suggests a different phytoplankton species emerged or expanded right after the extinction. Interestingly, this biomarker was not detected in any of the warm-water samples from Italy, China, or Türkiye.

That absence points toward a cold-water specialization—meaning only high-latitude environments hosted the phytoplankton species that produced phytanyl toluene.

What the Samples From Warmer Regions Showed

In the warmer Tethys Ocean regions, the researchers found:

- Much lower levels of C33–n-ACH overall

- A smaller post-extinction increase compared to Svalbard

- No detectable phytanyl toluene

This strongly suggests that warm lower-latitude seas were too unstable or too inhospitable for the algae species thriving in the Arctic refuges.

Given that tropical and subtropical waters were more affected by temperature spikes, anoxia, and chemical disturbances, this regional difference makes ecological sense.

Why This Matters: Survival in Cold Refuges

The core takeaway from the research is that higher-latitude marine environments acted as refuges during the Great Dying.

Why Were These Regions Safer?

- Cooler water temperatures

- More stable nutrient availability

- Less severe ocean warming

- More favorable oxygen levels

Because the global extinction was driven partly by extreme warming and low-oxygen oceans, areas farther from the equator became places where life could hold on.

The bloom of phytoplankton—especially the ones showing up in biomarker form—likely sustained:

- Small zooplankton

- Early recovering food webs

- Surviving marine animals

Without these algae blooms, post-extinction recovery might have been even slower or even impossible.

Understanding the Great Dying in Context

To appreciate the significance of this new research, it helps to look briefly at what caused the extinction.

Main Drivers of the Great Dying

- Massive volcanic activity from the Siberian Traps

- Huge releases of CO₂ and methane

- Rapid global warming

- Severe ocean acidification

- Spreading anoxia (oxygen depletion)

- Disruption of the global carbon cycle

These combined effects destroyed coral reefs, wiped out countless marine invertebrates, and nearly collapsed the marine food chain.

But the new biomarker evidence shows that life didn’t collapse uniformly everywhere. Instead, it retreated to regions where environmental conditions remained just tolerable enough.

Additional Context: Why Biomarkers Are So Valuable

Biomarkers allow scientists to detect the presence of organisms even when:

- No visible fossils remain

- Organic tissues have long disappeared

- The species had no shells or hard parts

C33–n-ACH and phytanyl toluene are especially useful because they are stable, durable, and highly diagnostic of certain algal groups.

Because these molecules survive when other evidence doesn’t, they help reveal ecological patterns that would otherwise remain hidden.

What Remains Unknown

Even with the detailed chemical evidence, several questions remain:

- The exact species of phytoplankton producing the biomarkers is unknown.

- Scientists still don’t know how widespread these blooms were beyond the studied sites.

- It’s unclear how quickly these cold-water ecosystems transferred energy up the food chain.

- More sampling across other high-latitude locations is needed to confirm this pattern globally.

Still, the study presents some of the strongest evidence yet for regional ecological refuges during Earth’s worst biological crisis.

Why This Research Matters Today

While the modern world is very different from the Permian, this study offers an important lesson:

Ecosystems don’t respond to global change uniformly.

Cooler regions can sometimes act as natural buffers, allowing key species to survive when environmental stress peaks elsewhere.

This doesn’t mean today’s climate crisis will play out the same way—but it does show how environmental variation can preserve biodiversity, even during planetary upheavals.

Research Paper

Phytoplankton Blooms on the Barents Shelf, Svalbard, Associated With the Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025AV001785