Manganese’s Unexpected Role in Weakening the Lyme Disease Bacterium

Lyme disease has been a persistent medical challenge for decades, affecting hundreds of thousands of people every year and often leaving long-lasting symptoms when not treated quickly.

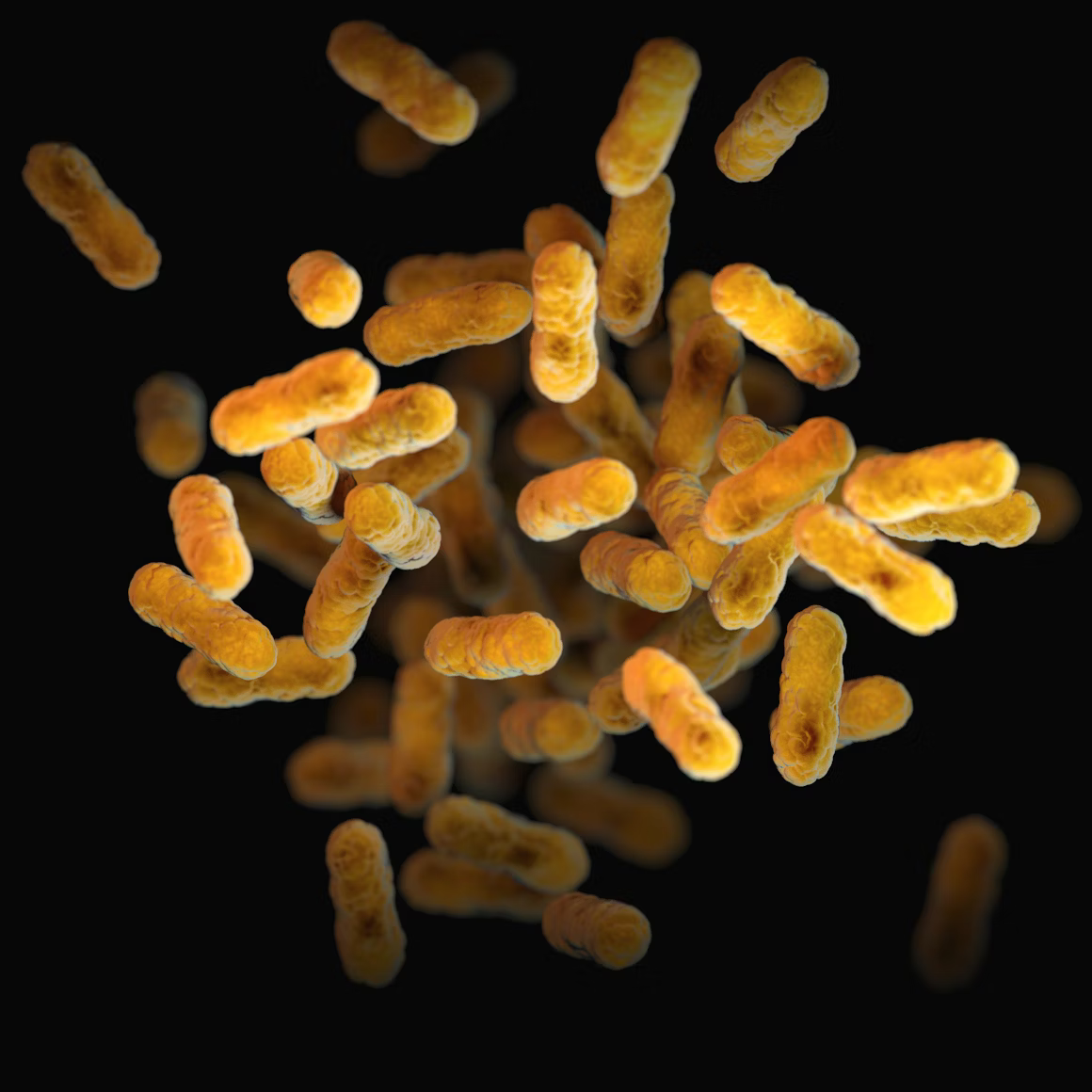

A new study published in mBio sheds light on a surprising vulnerability in the bacterium responsible for this illness, Borrelia burgdorferi, revealing a weakness that could eventually lead to new treatment strategies. Researchers from Northwestern University and the Uniformed Services University (USU) discovered that the mineral manganese, long known to help the bacterium survive inside the human body, also has the potential to become its downfall. The finding is important because it exposes a critical balance that the pathogen must maintain, and disrupting that balance could make it easier to fight.

The bacterium that causes Lyme disease is unusual compared to many other disease-causing microbes. Instead of using iron as a key component in essential biochemical processes, it relies heavily on manganese, using it to protect itself from the damaging molecules produced by the human immune system. These damaging molecules, often called reactive oxygen species, are meant to kill invading pathogens. Borrelia burgdorferi’s ability to withstand them is part of what makes the infection so persistent. The new study shows in great detail how the bacterium manages this, and how this same survival strategy can turn into a major vulnerability under the right conditions.

To investigate the role of manganese inside the bacterium, the scientists used two powerful tools: electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) imaging and electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectroscopy. These advanced techniques let researchers examine the actual atomic environment inside living bacteria without destroying or altering them. This means they could map out where manganese is stored, how it is used, and how its role changes when the bacterium is under stress. The resulting analysis revealed that Borrelia burgdorferi uses a two-tier defense system that depends entirely on manganese.

The first part of this system involves an enzyme called MnSOD, which acts like a protective shield. MnSOD neutralizes harmful oxygen radicals before they damage important molecules in the bacterium. The second part of the defense involves a pool of manganese-based metabolites, which work like a sponge to mop up any reactive molecules that manage to get past the initial shield. Together, these two layers give the bacterium impressive resilience against attacks from the immune system.

What makes this discovery especially interesting is that the bacterium must constantly divide its limited supply of manganese between these two defense systems. Too little manganese means neither the enzyme shield nor the metabolite sponge can function properly. But too much manganese creates a different problem: the bacteria become overwhelmed by the excess metal. As Borrelia burgdorferi cells age, their pool of protective metabolites shrinks dramatically. If extra manganese enters when the metabolite pool is depleted, the bacterium cannot store the mineral safely, and the surplus becomes toxic. This reveals a precarious balancing act the bacterium must perform. When the balance fails, its defenses collapse.

This discovery is important because it opens the door to a new way of targeting Lyme disease. Current treatments rely mainly on antibiotics, and while they can be effective, long-term use can cause problems, including the destruction of beneficial gut bacteria. In addition, there is still no approved vaccine for Lyme disease, and the number of annual cases in the United States is estimated at around 476,000, according to the CDC. Because Borrelia burgdorferi depends so heavily on manganese for survival, disrupting its ability to manage this metal could make it far more vulnerable.

Researchers suggest several possible therapeutic strategies based on this idea. One approach could be to starve the bacterium of manganese entirely, which would shut down both parts of its antioxidant defense. Another possibility would be to interfere with the formation of manganese-based metabolites, preventing the bacteria from neutralizing harmful molecules even if MnSOD remains active. A more aggressive approach could be to push the bacterium into manganese overload, especially at stages when its protective metabolite pool is naturally low. Overloading it with manganese under those conditions could be enough to trigger toxic damage.

An intriguing aspect of this study is that the researchers have previously investigated manganese in a completely different organism: Deinococcus radiodurans, a bacterium sometimes called “Conan the Bacterium” for its ability to withstand extreme radiation. Their earlier work on how manganese protects Deinococcus from DNA damage inspired them to examine whether a similar mechanism existed in Borrelia burgdorferi. The fact that manganese plays such a key role in the survival of both organisms shows how fundamental this metal can be in microbial resilience, but it also shows how these pathways can be exploited as weaknesses.

While the study uncovers valuable information, some questions remain open. One of them is the exact location of the MnSOD enzyme within Borrelia burgdorferi. The researchers suggest that it may be positioned near the surface of the bacterium, which would allow it to intercept immune-generated radicals, but this still needs to be confirmed experimentally. Another question is how the findings translate to real infections inside a human body, where nutrient availability, immune pressures, and bacterial metabolism can be quite different from laboratory conditions.

Still, the research provides a detailed and convincing picture of how Borrelia burgdorferi manages manganese and how that management determines whether it survives or collapses under stress. It also demonstrates how modern imaging and spectroscopy tools can reveal biochemical processes that would otherwise remain completely hidden. This kind of insight is valuable because it helps scientists identify precise molecular targets rather than relying solely on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Additional Information About Lyme Disease and Borrelia burgdorferi

Lyme disease is primarily transmitted through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks. Early symptoms often include fever, fatigue, headache, and the characteristic bullseye-shaped rash known as erythema migrans. When treated promptly with antibiotics, many people recover fully. However, delayed treatment can allow the bacterium to spread to the nervous system, joints, and heart, leading to more severe complications.

Borrelia burgdorferi is known for its unusual biology. Besides its reliance on manganese instead of iron, it also has a slow replication cycle, which may contribute to the lingering nature of the disease. Its corkscrew shape helps it move through dense tissues, including connective tissue, which allows it to spread efficiently inside the body.

Because Lyme disease remains one of the fastest-growing vector-borne diseases in many countries, understanding these unique features is crucial for developing better diagnostics, treatments, and possibly future vaccines.

Research Paper:

https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.02824-25