Scientists Call for a Bigger Research Toolbox as Genetic Advances Unlock Earth’s Biodiversity

Recent breakthroughs in genetics have opened the door to studying an enormous range of life on Earth, and a growing number of scientists now believe it’s time to rethink how research is done. For decades, biology has leaned heavily on a handful of familiar laboratory species—mice, zebrafish, fruit flies, roundworms, frogs, and yeast. These organisms became the standard because they were easy to keep, easy to breed, and, most importantly, their genetics were well-mapped early on. But despite the success of these traditional models, new genetic technologies are revealing that they represent only a tiny sliver of the planet’s biological innovation.

A new commentary published in Nature Reviews Biodiversity—led by Michigan State University evolutionary biologist Jason Gallant—makes the case that the research world should expand far beyond the usual lab animals. According to Gallant, the ability to sequence, manipulate, and analyze the genomes of previously “difficult” or “unconventional” organisms means scientists now have a supersized research toolbox at their disposal. With roughly 8.7 million species estimated to be alive today, he argues that focusing mostly on traditional models risks overlooking countless biological solutions to major global challenges.

The traditional system has strengths, but it’s not perfect. More than 80% of potential therapeutics developed in mouse models fail when tested in humans, highlighting major limitations in relying too heavily on one type of organism for biomedical research. These standard models also don’t offer much insight into urgent issues like climate adaptation, ecosystem resilience, or large-scale environmental change.

Gallant and his colleagues believe researchers should integrate a wider diversity of plants, animals, and microbes into everyday science—especially now that advances in genomics make such work easier than ever.

Why Scientists Want to Move Beyond the Mouse

Gallant points out that across the plant and animal kingdom, life has come up with extraordinary evolutionary innovations. Many species have disease resistance, unique metabolic pathways, extreme physiological abilities, and specialized symbiotic relationships. These aren’t random quirks—they’re solutions refined over millions of years of evolution. And many of them remain scientifically untapped.

Traditional model organisms are convenient, but they can’t represent the enormous range of adaptations found across the tree of life. As Gallant argues, sticking too closely to those familiar models means we’re leaving countless discoveries untouched. With modern genetic tools, researchers can now explore organisms specifically chosen for the questions they want to answer, rather than squeezing every question into the same handful of species.

He emphasizes that researchers today have powerful genomic datasets, CRISPR tools, large sequencing platforms, and increasingly sophisticated computational methods. These tools allow scientists to analyze and manipulate the biology of species that previously would have been extremely difficult—or impossible—to study at a detailed level.

The Surprising New Species Entering the Research Spotlight

One of the most exciting developments in modern biology is the rise of new model systems beyond the standard lab lineup. Gallant highlights several species with enormous scientific potential:

Electric Eels

Gallant’s own Electric Fish Lab studies electric eels to understand nervous-system proteins. Electric fishes have evolved specialized electric organs that allow them to navigate, communicate, and even hunt. Their unique biology may offer insights into neural signaling, bioelectricity, and even prosthetic limb control.

Octopuses

Octopuses have incredibly complex nervous systems, with decentralized neural networks spread across their arms. Their abilities—problem-solving, camouflage, flexible movement—could help researchers understand new forms of neural control and may inspire robotics and neural engineering.

Sea Sponges

Sponges have already contributed molecules that led to life-saving drugs in human medicine. They possess unusual biochemical pathways that make them a rich source of natural compounds for research into new pharmaceuticals.

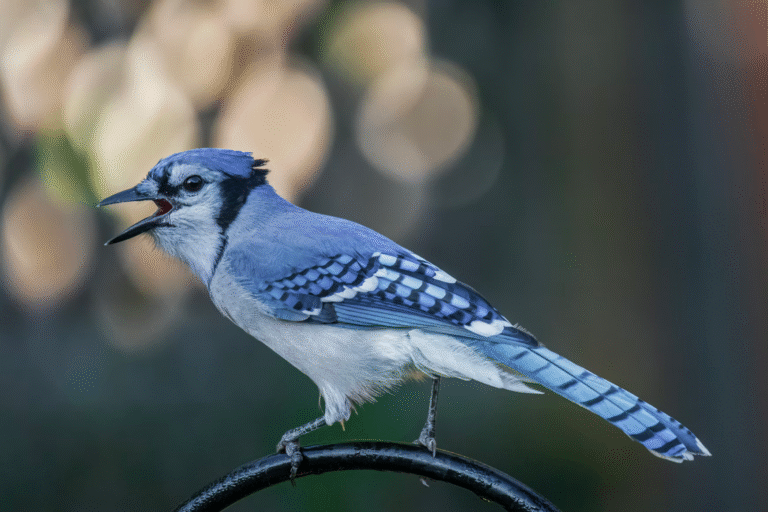

Birds

Birds evolve quickly in response to environmental pressures. Their rapid adaptations offer valuable clues into climate resilience, migration biology, and evolutionary change. Their biology may also help researchers understand how organisms cope with rapidly shifting ecosystems.

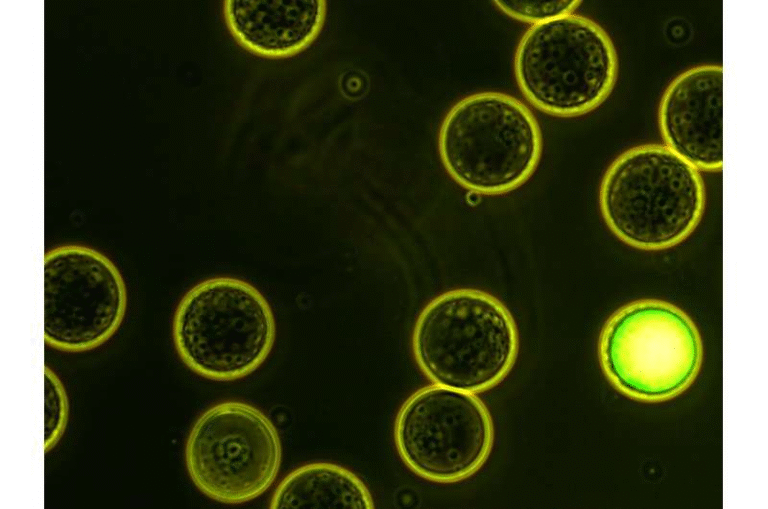

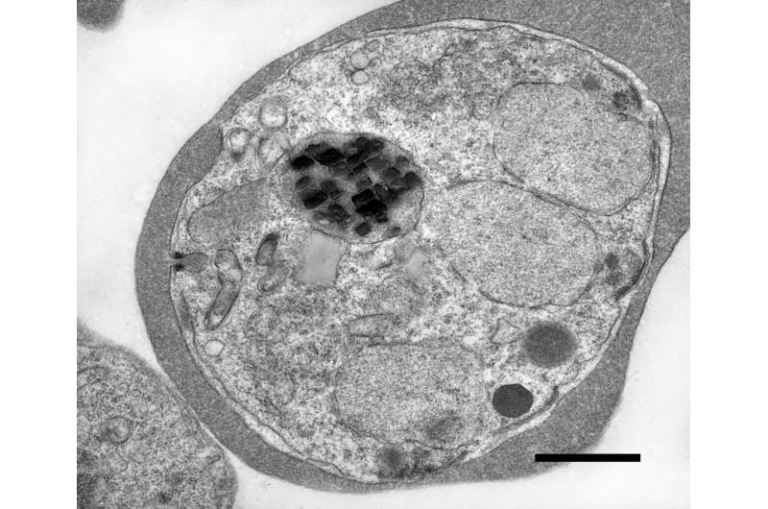

Bacteria With Unique Abilities

Certain bacteria can consume plastics, break down toxic materials, or survive in extreme environments. These microbes could be used to clean oceans, degrade pollutants, or help develop sustainable materials—real-world applications that traditional lab organisms can’t provide.

Sea Lampreys

Lampreys produce specialized pheromones that scientists are already using to manage invasive populations in the Great Lakes. They offer a real example of using evolutionary biology to create practical ecological tools.

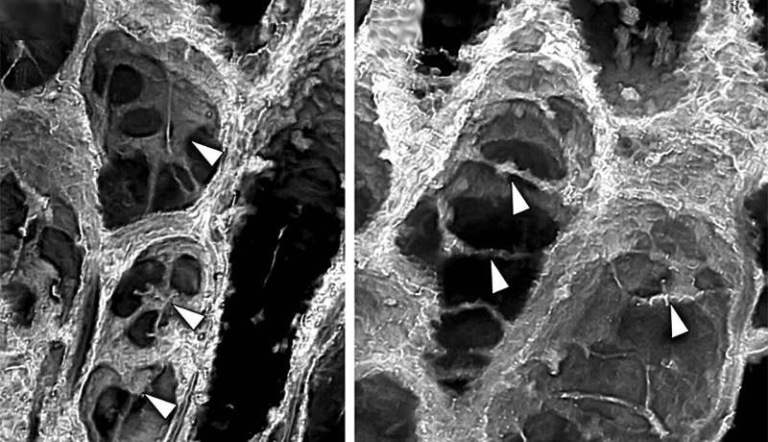

Rough-Skinned Newts

These newts can produce one of the world’s most potent neurotoxins—tetrodotoxin—yet avoid poisoning themselves. Understanding this unique biology could help create safer treatments or reveal new biochemical pathways.

These examples show how broadening research species can directly contribute to biomedical innovation, environmental solutions, and understanding fundamental biology.

The Challenges With Embracing New Model Organisms

While the opportunities are huge, Gallant acknowledges that shifting away from traditional models isn’t easy. Research culture is built around mice and other standard organisms, with funding, training programs, patent systems, and lab infrastructure all designed to support those models.

Scientists who study unconventional organisms often follow a lonelier and more difficult path. They must figure out how to house the animals, develop new lab protocols, create genetic databases, and troubleshoot problems without the massive support communities available for mouse or fly research.

Physical and academic silos also cause problems. Many researchers studying different species or different ecological systems may be in separate buildings, departments, or funding categories—even within the same university. This fragmentation slows collaboration and makes it harder to build shared expertise.

Gallant argues that universities need to invest in shared infrastructure, cross-disciplinary programs, and training that supports research across a wide diversity of organisms. He believes scientists should be trained to work more flexibly, combining ecology, evolution, genetics, and high-tech biology instead of staying within narrow boundaries.

Despite the challenges, he emphasizes that scientists don’t need to abandon traditional models—they simply need to invite the rest of life into the lab.

How Universities Are Responding

Michigan State University offers several examples of how this shift is already happening:

- Researchers are creating pipelines for studying biodiversity under programs related to ecology, evolution, and behavior.

- Bacteria research groups have developed methods to “bottle evolution”, allowing scientists to watch rapid changes in microbial populations.

- Multiple teams use innovative biological systems—from invasive species pheromones to neurotoxin-resistant amphibians—to solve practical problems.

Professor Elise Zipkin, director of MSU’s Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior graduate program, supports Gallant’s call. She stresses that while interdisciplinary groups are valuable, specific investments in infrastructure are essential to truly accelerate scientific discovery and education.

A Future Where Biodiversity Shapes Science

The message behind Gallant’s commentary is straightforward: with today’s genetic tools and massive biodiversity datasets, continuing to rely on the same few species is a missed opportunity. Evolution has already performed billions of years of biological “experiments.” By studying a wider diversity of organisms, we could uncover new mechanisms, new medicines, new materials, and new ideas that traditional models can’t provide.

The future of research may be one where classrooms, laboratories, patent offices, and funding agencies all embrace a more diverse view of life. And as Gallant puts it, after the genetic leaps of recent years, it would be hard to justify ignoring the untapped potential across Earth’s vast biodiversity.

Research Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00098-x