New Experimental Drug Shows Strong Protection Against Acute Kidney Injury in Mice by Targeting Ceramides

Acute kidney injury, or AKI, remains one of the most serious and unpredictable medical emergencies. It develops suddenly, often after events like sepsis, heart surgery, or other major physiological stressors. More than half of ICU patients experience some form of AKI, and the condition can be life-threatening. Even if someone recovers short-term kidney function, AKI frequently increases the long-term risk of chronic kidney disease. Despite decades of research, there are still no approved drugs that can prevent or treat AKI directly.

Now, a new study from University of Utah Health reports a major step forward: researchers have identified that AKI is triggered by harmful fatty molecules called ceramides, and an experimental drug that alters the way ceramides are produced was able to protect kidney mitochondria and fully prevent kidney injury in mice. The findings were published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

This rewritten article breaks down everything found in the news report and expands on it with additional context about AKI, ceramides, mitochondria, and kidney physiology.

Understanding How Ceramides Trigger Acute Kidney Injury

The Utah researchers had previously shown that ceramides can damage tissues in other organs, including the heart and liver. In the new study, they analyzed ceramide behavior during AKI in both mouse models and human urine samples. The pattern was extremely clear: ceramide levels spiked sharply following kidney injury.

Ceramides rose quickly after the damage occurred and increased proportionally with the severity of the injury. In other words, worse kidney injury meant higher ceramide levels. Because this rise happens early—often before overt symptoms—urinary ceramides show promise as an early biomarker for AKI. For example, patients undergoing heart surgery (a situation where about one-quarter of people develop AKI) could potentially be screened before symptoms appear.

But correlation wasn’t the end of it. The team found that ceramides directly injure kidney mitochondria, the cell’s essential energy generators. When mitochondria fail, cells in the kidney’s proximal tubule—the segment most sensitive to damage—lose energy, deform structurally, and begin a cascade of cell death and inflammation that leads to full-blown AKI.

Genetic Modification and Drug Treatment Both Prevented AKI in Mice

To test ceramides’ role more directly, researchers made a precise genetic modification in mice. This change disrupted how ceramides are produced by altering a key enzyme in the ceramide synthesis pathway. As a result, the genetically altered animals became what the researchers described as “super mice”—they did not develop AKI even under conditions that normally cause severe kidney injury.

In the next phase, the team used a new drug candidate developed by Centaurus Therapeutics, a biotechnology company co-founded by one of the study’s senior researchers. The drug reduces ceramide levels by targeting ceramide metabolism. After administering the drug to mice before exposing them to kidney stress, the researchers observed that:

- Kidney function remained normal

- Mice stayed fully active

- Kidneys appeared nearly normal under the microscope

- Mitochondria remained long, intact, and functional

This was remarkable because the experimental model they used typically produces strong, predictable stress on the kidneys. Yet the drug-treated mice showed little to no injury.

What Actually Happens to Mitochondria During AKI?

Under normal conditions, mitochondria in kidney cells maintain a specific elongated, structured shape that supports efficient energy production. AKI disrupts this: mitochondria become malformed, fragmented, and unable to generate energy.

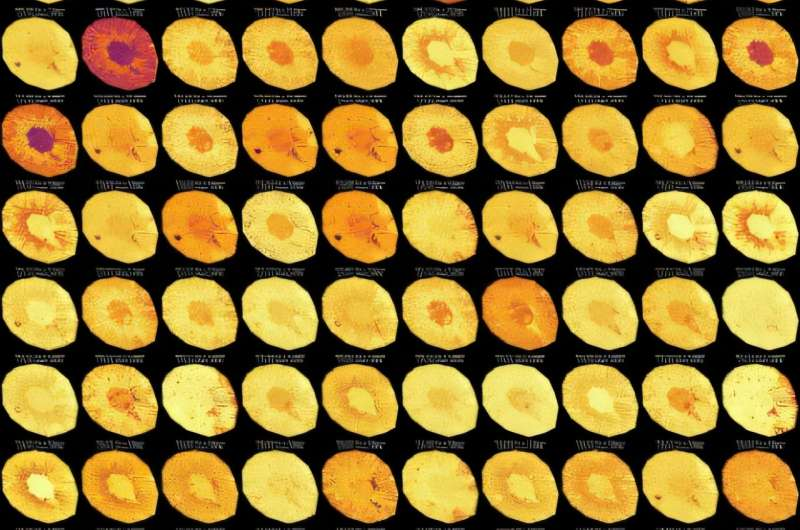

The study’s images showed striking differences between untreated and treated animals. In untreated AKI models, mitochondrial architecture—including their inner membranes, cristae, and respiratory complexes—was damaged. In contrast, mice with altered ceramide production or drug treatment maintained normal mitochondrial structure, even under significant stress.

This establishes a clear mechanism: ceramides damage mitochondria, and reducing ceramide levels protects them, preventing the entire cascade of injury.

Why Ceramides Matter: A Quick Background

Ceramides belong to a group of lipids called sphingolipids, which play essential roles in cell structure and signaling. Under normal circumstances, ceramides help regulate processes like:

- Cell growth

- Cell death

- Stress responses

- Membrane structure

But when produced in excess, ceramides can become toxic, promoting inflammation, energy disruption, and cellular dysfunction. In tissues like the kidney, which rely heavily on mitochondrial energy production, ceramide overload can be particularly destructive.

Abnormal ceramide levels have also been linked to:

- Heart failure

- Type 2 diabetes

- Fatty liver disease

- Neurodegenerative conditions

Because mitochondria are central to these diseases, the research team believes that the ceramide-modulating drug might also have broader therapeutic potential beyond AKI.

The Drug Used in the Study Is Not the Same as the One in Human Trials

An important detail clarified by the researchers is that the compound used in this study is closely related to—but not identical to—the ceramide-lowering drug that has already moved into human testing. The experimental drug from this study is considered a backup compound. While its protective effects were strong, long-term safety research is still required.

The team emphasized that results in mice do not always translate directly to humans. The next steps involve:

- Ensuring safety in additional animal studies

- Verifying dosing thresholds

- Understanding potential side effects

- Comparing genetic vs. pharmaceutical ceramide reduction

- Investigating how timing affects outcomes (before vs. after kidney injury)

Even with these cautions, the researchers are optimistic because the protective effects in mice were unusually complete.

Acute Kidney Injury: What It Is and Why It’s Difficult to Treat

To give readers more background, here’s a quick overview of AKI itself.

AKI is a rapid decline in kidney function, often occurring within hours or days. It is commonly caused by:

- Hypoxia (reduced blood flow)

- Sepsis

- Major surgeries, especially cardiac operations

- Toxin exposure

- Severe infections

- Medication-related kidney stress

Symptoms may include:

- Reduced urine output

- Fluid retention

- High creatinine levels

- Fatigue

- Confusion

- Swelling

But early stages are often silent, which is why biomarkers like urinary ceramides could be game-changing.

Treatment currently focuses on:

- Supporting kidney function

- Managing fluids

- Avoiding additional kidney stress

- Treating the underlying condition

There are no approved drugs that directly interrupt the cellular mechanisms of AKI. That’s why the new ceramide-focused approach is attracting attention.

Could This Become a Real Therapy for Humans?

If future tests demonstrate safety, researchers envision giving such a drug to people before high-risk procedures, especially heart surgery. With about 25% of such patients developing AKI, preventive treatment could significantly reduce complications and long-term kidney decline.

Because the drug works at the level of mitochondrial protection, it may also be useful in other diseases where mitochondrial damage is central.

Research Reference

Therapeutic Remodeling of the Ceramide Backbone Prevents Kidney Injury

https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(25)00440-1