New Evidence Shows How Smarter Tuberculosis Screening Can Protect High-Risk Prison Populations

Tuberculosis continues to be one of the world’s leading infectious killers, even though it is both preventable and treatable. Every year, millions of people fall ill with the disease, and gaps in early detection remain one of the biggest barriers to reducing transmission. These gaps are especially visible in high-risk environments, and one of the highest-risk of all is the prison system. Overcrowding, poor ventilation, limited medical access, and high rates of comorbidities make prisons a place where TB spreads far more easily than in the general population.

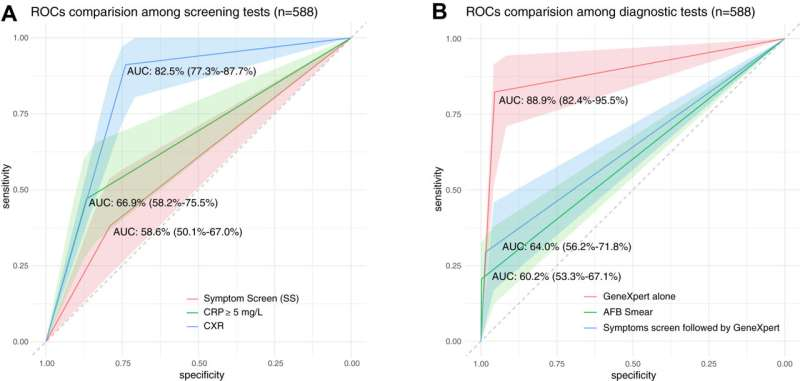

A new study led by researchers from Yale and published in The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific takes a close, data-focused look at how TB screening can be significantly improved in Malaysian prisons. Instead of depending solely on symptom checks – which is still the norm in many correctional systems worldwide – the researchers tested multiple screening tools side-by-side to understand which methods actually catch the most cases. Their findings could help reshape TB control strategies not only in Malaysia but in correctional facilities globally.

The study took place at Kajang Prison, Malaysia’s largest correctional facility, and involved more than 500 men entering the prison. Traditionally, a person is only tested further for TB if they report symptoms such as a persistent cough, weight loss, or fever. But the research team expanded the screening process to include chest X-rays and a simple blood test for C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammation marker. After these initial screenings, confirmatory tests using acid-fast bacilli smear, Xpert molecular testing, and bacterial culture were performed.

The results showed clearly that relying on symptoms alone would miss many active cases. Chest X-rays, in particular, demonstrated the highest sensitivity, flagging individuals who would have otherwise slipped through the cracks. CRP blood testing, while less powerful than X-ray screening in general, performed especially well among people living with HIV, a group at higher risk for TB progression and harder-to-detect disease. This suggests that different populations may require different screening strategies to maximize detection.

Another major point the researchers highlight is the value of identifying latent TB infection – the dormant form of the disease that can activate later. Prisons are known to have a very high prevalence of latent TB, often many times higher than the general population. Detecting and treating latent infection is crucial, because it helps break the chain of transmission before it progresses into contagious disease. Strengthening screening at prison entry gives health systems a unique chance to reach people who may otherwise have no interaction with medical services.

The study’s findings also align with ongoing efforts by Malaysia’s Ministry of Health, which has shown interest in improving prison health practices. The research team reports productive discussions and enthusiasm from Malaysian officials about implementing more practical and effective methods inside correctional settings. That matters, because many countries face the same challenge: how to upgrade public-health practices in environments that are often under-resourced and overlooked.

Why Prisons Are a Critical Battleground for TB Control

The World Health Organization regularly emphasizes that TB incidence in prisons can be up to ten times higher than in the general population. This isn’t surprising when you consider the factors at play inside correctional facilities: high population density, close contact between individuals, limited movement, chronic health issues, and lack of consistent access to healthcare. When one person with active TB enters a poorly ventilated, crowded environment, transmission can happen quickly.

People incarcerated also often come from marginalized backgrounds, with higher rates of HIV, hepatitis C, substance use disorders, and unstable living conditions prior to imprisonment. These factors all increase the chance of developing TB and the likelihood of passing it on. Improving screening inside prisons isn’t just about protecting incarcerated individuals – it helps reduce transmission into the wider community once people are released.

What This Study Adds to Existing Research

Previous work in Kajang Prison and other detention settings has shown alarmingly high rates of latent TB infection, sometimes exceeding 60% of the population. This means large numbers of people are carrying the bacteria silently, with the potential to develop active disease later. The new study adds another important layer of evidence by showing how to detect active disease more accurately at the point of prison entry.

The finding that chest X-rays perform best overall isn’t surprising, as X-rays have long been used in TB screening. However, confirming that CRP testing is particularly useful for people with HIV is an important insight, especially in settings where radiography may be harder to access. CRP tests are inexpensive, quick, and require minimal equipment, making them a strong option for lower-resource facilities.

The study also reinforces the superior performance of molecular testing (Xpert) over traditional smear microscopy for diagnosis. While many countries still rely on smear tests due to cost or availability, the greater accuracy of molecular testing means it can catch cases earlier and reduce the number of false negatives.

The Bigger Picture: Improving TB Control Worldwide

TB control efforts have struggled in many parts of the world due to insufficient funding, inconsistent screening, and limited access to newer diagnostic tools. In Southeast Asia, where Malaysia is located, TB remains a major public-health burden. Studies like this help decision-makers prioritize investments and focus on interventions that have the greatest impact.

Better prison screening can help in several ways:

- It identifies infected individuals earlier, reducing spread within the facility.

- It uncovers cases that might otherwise go unnoticed.

- It opens the door to treatment for latent infection, which reduces future active cases.

- It protects the broader public by reducing the number of infectious individuals re-entering the community.

- It helps create standardized screening protocols that can be applied in other countries facing similar challenges.

Additional Information About Tuberculosis

TB is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which most commonly affects the lungs but can impact other organs. The disease spreads through the air when a person with active pulmonary TB coughs, speaks, or sneezes. One important fact is that only active TB is contagious, not latent TB.

Key points about TB include:

- Latent TB infection means the bacteria are present but inactive; there are no symptoms, and the person is not contagious.

- Active TB disease occurs when the bacteria multiply and cause symptoms like persistent cough, fever, night sweats, and weight loss.

- People with weakened immune systems – especially those with HIV – are far more likely to progress from latent to active TB.

- TB remains one of the top global infectious killers, alongside HIV and malaria.

- Modern treatment is effective but must be taken for several months, and interruptions can lead to drug-resistant forms of the disease.

- Early detection is one of the most important strategies for reducing spread, especially in crowded environments.

Moving Forward

This research makes a strong case for expanding TB screening beyond simple symptom questionnaires. By adding chest X-rays and CRP blood tests to the process, prisons can catch more cases earlier and protect both incarcerated individuals and the communities around them. The partnership between researchers and Malaysia’s Ministry of Health is a promising sign that practical improvements may follow.

With TB still affecting millions worldwide, especially in vulnerable populations, improving screening in prisons could become a crucial part of global TB-control strategies. Studies like this help clarify what works best, in which populations, and under what conditions – giving policymakers data they can use to make real-world decisions.