How Early Hearing Loss Disrupts Infant Brain Development and Why Fast Intervention Matters

New research published in Science Advances presents a detailed look at how infants born with congenital sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) experience disrupted patterns of brain development within the first few months of life. This study is one of the most comprehensive examinations to date of how early auditory deprivation can alter the brain’s natural organization, and it underscores the urgency of providing early access to sound and language.

In this article, I’ll walk through every major finding, the specific data, the research methods, and the implications. After that, I’ve included some additional sections covering background information about how infant brain development normally progresses, why hemispheric specialization matters, and what current technologies can (and cannot) do for babies with hearing loss.

Let’s go through it all clearly and directly.

What the Study Examined

Researchers from the University of California, Merced and Beijing Normal University conducted a study involving 112 infants between 3 and 9 months old. The group included:

- 52 infants with congenital SNHL

- 60 infants with typical hearing

The goal was to understand how hearing loss affects the early development of brain networks, particularly the way the left and right hemispheres begin to specialize.

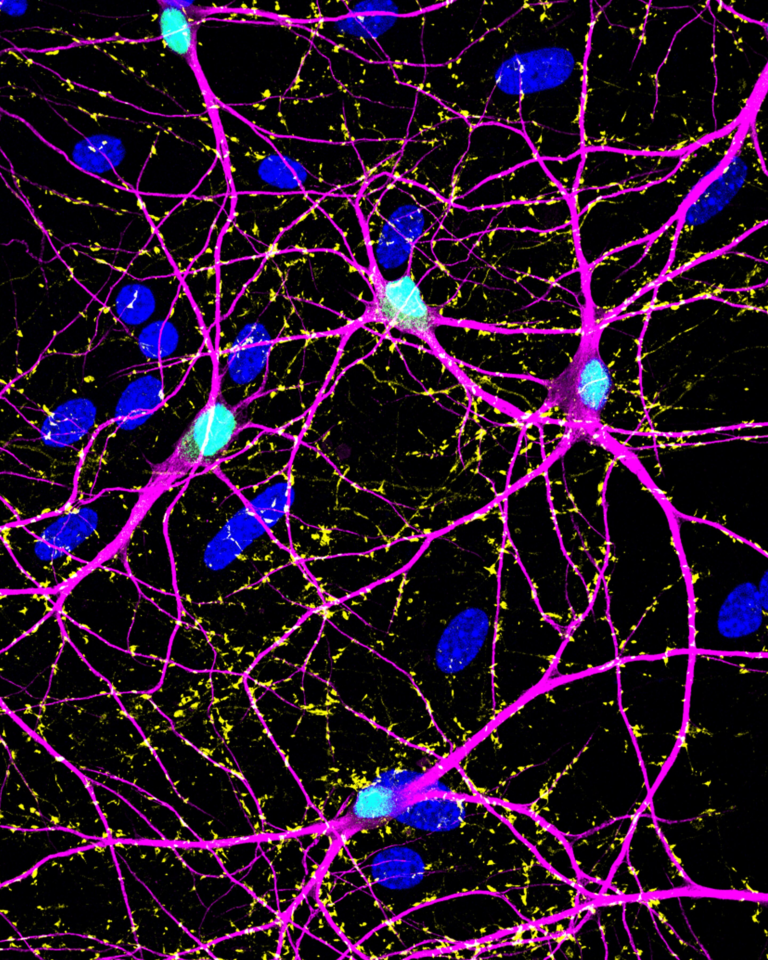

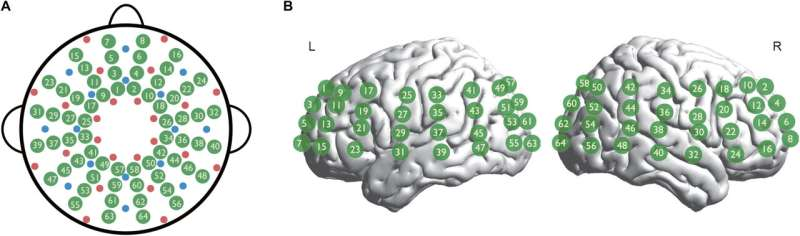

To do this, the team used a noninvasive imaging technique called functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). This method tracks how different areas of the brain communicate by measuring blood flow dynamics. The researchers placed 64 measurement channels on the infants’ scalps, each made up of source and detector pairs. They also performed MRI coregistration in a subset of infants to precisely map which fNIRS channels aligned with which brain regions.

This setup allowed them to analyze connectivity across the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes of both hemispheres.

What They Found About Brain Organization

Both hearing and hard-of-hearing infants showed “small-world network organization.” This term means the brain maintains efficient communication both locally and across distant regions—a pattern normally associated with healthy brain function.

However, the critical difference appeared in hemispheric asymmetry, particularly involving the left hemisphere, which usually becomes more dominant in early life.

Typically hearing infants showed a clear developmental trend:

- As they aged from 3 to 9 months, their left hemisphere became increasingly specialized.

- This asymmetry supports the foundations for language, symbolic understanding, reasoning, and memory.

Infants with SNHL, however, did not show this shift toward left-hemisphere dominance.

The mismatch was especially strong in infants with moderate to profound hearing loss, who displayed almost no normal left-hemisphere specialization. Infants with mild hearing loss retained some degree of typical left-side organization, suggesting that even low levels of auditory input offer protective effects.

Why Hemispheric Asymmetry Matters

The human brain isn’t symmetrical in function. The left hemisphere generally becomes the home of:

- speech processing

- structured language

- symbolic communication

- sequential reasoning

This lateralization begins extremely early. By a few months of age, hearing infants already show clear left-dominant patterns linked to processing the rhythms, contours, and patterns of human speech.

Without adequate auditory input or accessible language exposure, this natural pattern doesn’t emerge in the same way.

That means the issue isn’t limited to the ears. As the study points out, congenital hearing loss should be understood as a brain-development issue affecting the formation of essential cognitive networks.

Why Early Language Exposure Is Critical

One important detail highlighted by the researchers is that the brain needs structured linguistic input, not necessarily sound alone, to develop normally.

Past work has shown that:

- Deaf infants born to deaf parents

- Who receive early exposure to sign language

- Still develop normal left-hemisphere specialization

This finding reinforces that it’s language access, not only auditory access, that builds the neural architecture needed for learning and communication.

The authors emphasize that the first year—and especially the first few months—form a critical window. Neural plasticity is extremely high during this period, and the brain is actively building communication networks that will influence later language development, memory systems, and cognitive skills.

If infants do not receive auditory input through hearing aids or cochlear implants, or if they don’t receive sufficient sign language exposure, the left and right hemispheres can develop out of balance.

Why the Researchers Consider This Urgent

The study stresses the need for early, rapid intervention. Specifically:

- Hearing aids

- Cochlear implants

- Early sign language environments

All of these can help preserve or stimulate typical network development.

The researchers also note that because the study only looked at infants at one point in time, future longitudinal studies are needed. They plan to follow children further into early childhood to understand:

- how brain asymmetry changes over time,

- whether intervention can restore typical patterns,

- and how brain function relates to later language and cognitive outcomes.

They also propose combining fNIRS, MRI, and EEG in future work to get a clearer picture of how sound, language, and brain development interact.

What fNIRS Brings to This Type of Research

Because fNIRS is safe, silent, and comfortable, it allows scientists to measure brain activity in infants who would otherwise be unable to participate in traditional neuroimaging. It offers:

- high tolerance for movement

- wearable probe arrays

- the ability to test awake infants

- good spatial mapping when matched with MRI

- detailed network-level information

This makes it one of the few tools well-suited for studies of very young babies, especially those with sensory differences.

Additional Background: How Hearing Shapes Early Brain Development

Even before birth, infants are exposed to low-frequency speech rhythms through the womb. After birth, auditory pathways strengthen rapidly as babies begin processing:

- pitch patterns

- speech rhythms

- phonemes

- human voices

- environmental sounds

These early experiences drive the refinement of the auditory cortex and form the foundation for later language learning.

When hearing loss occurs at birth:

- the auditory cortex receives limited input,

- the typical strengthening of circuits slows or stops,

- and adjacent brain regions may reorganize to compensate.

This reorganization is not inherently negative, but it can interfere with the establishment of typical language pathways.

The earlier the brain receives alternative structured inputs—like sign language—the more smoothly it can establish stable linguistic networks.

Technologies Used for Early Auditory Support

Babies diagnosed at birth with hearing loss may receive:

Hearing Aids

These amplify sound but rely on residual hearing. For infants with mild to moderate SNHL, hearing aids can support relatively natural auditory development.

Cochlear Implants

These devices bypass the nonfunctioning parts of the inner ear and stimulate the auditory nerve directly. For infants with profound SNHL, cochlear implants often provide their first access to sound.

Signed Languages

Languages like American Sign Language or Chinese Sign Language offer complete linguistic structure from birth. Signed languages fully support language development and can prevent delays even when auditory input is limited.

What This Study Changes

This research moves the field toward a clearer understanding that congenital hearing loss impacts neural architecture, not just auditory sensation. It reinforces the global consensus that delayed access to language—spoken or signed—can lead to long-term developmental consequences.

The key takeaway is simple but vital:

Infants need early, structured access to language of any form to support healthy brain development.

Waiting too long to provide access—whether through hearing devices or sign language—can alter hemispheric organization during one of the most sensitive periods of brain growth.

Research Paper

Developmental alterations in brain network asymmetry in 3- to 9-month infants with congenital sensorineural hearing loss

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx1327