Nonsurgical Gene-Guided Ultrasound Treatment Shows New Promise for Targeted Seizure Control

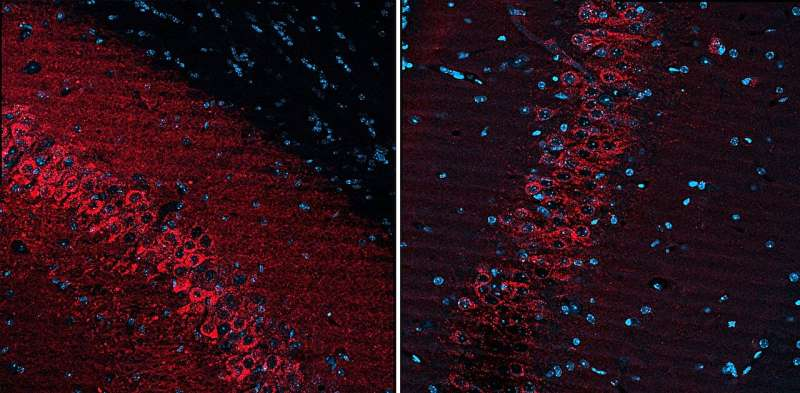

Researchers at Rice University have introduced a new nonsurgical method that may someday help control seizures by targeting specific brain circuits with remarkable precision. The work centers on a technique known as Acoustically Targeted Chemogenetics, or ATAC, which blends focused ultrasound, engineered viral gene delivery, and chemogenetic control to quiet overactive neurons in the brain. The latest study demonstrates this approach in mice, focusing on the hippocampus, a region often linked to seizure activity. The results show a clear ability to raise seizure thresholds using a one-time, targeted procedure followed later by a simple oral drug.

This new development is notable because it bypasses the need for invasive brain surgery or permanent implants—two standard approaches used to reach deep brain structures for seizure control. Instead, it introduces a strategy that uses low-intensity ultrasound to open extremely small, temporary pores in the blood-brain barrier, allowing an engineered therapeutic vector to slip into a precise brain region. After the genetic material is expressed in the targeted neurons, researchers can use a drug to “switch down” the activity of those cells. The rest of the brain remains unaffected, offering a level of control that traditional medication cannot match.

Below is a clear breakdown of what the study accomplished, how ATAC works, and why this could matter for future epilepsy treatments—as well as a deeper look at focused ultrasound, gene therapy, and chemogenetics for readers who may want more background.

How the New Procedure Works

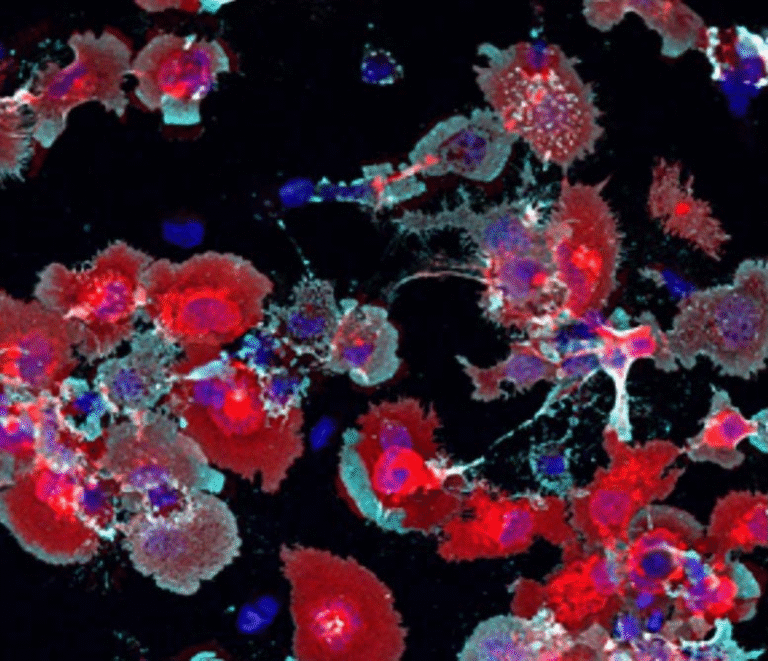

The study, published in the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience, showcases a step-by-step demonstration of the ATAC method in living animals. The process begins with the injection of microscopic, gas-filled microbubbles into the bloodstream. When low-intensity focused ultrasound waves are directed at the hippocampus, these bubbles vibrate against capillary walls, creating temporary openings in the blood-brain barrier. These openings measure only a few nanometers—large enough for viral vectors but too small for blood cells—helping maintain safety.

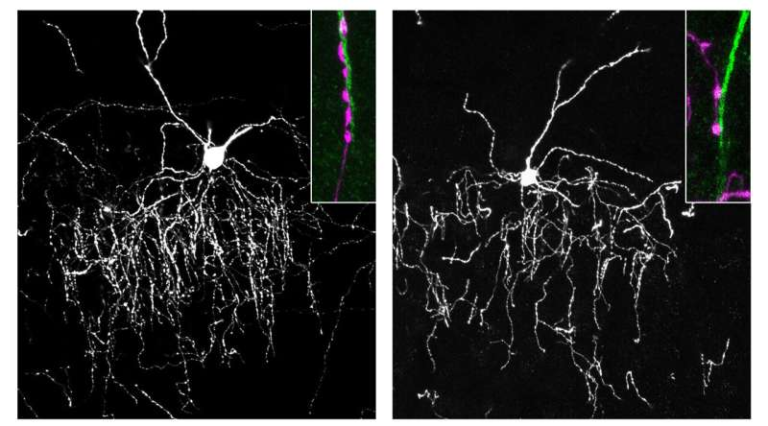

As these pores open, researchers introduce specially engineered viral delivery vectors, created in the same Rice University lab, that carry genetic instructions for a type of inhibitory chemogenetic receptor. These receptors act like a molecular dimmer switch, allowing neurons to quiet their activity when exposed to a specific systemically delivered drug.

Once the vectors pass into the hippocampus, the pores naturally close within hours, leaving the blood-brain barrier intact again. Over the following days, the neurons in the targeted region begin expressing the inhibitory receptors. Later, when researchers administer the activating drug orally, only the neurons carrying the engineered receptor respond, becoming less active. This lets researchers decrease hyperactivity in the precise region involved in seizures without affecting the rest of the brain.

The Rice team confirmed that the gene delivery reached the entire bilateral hippocampus, achieving high spatial resolution and strong expression. Imaging showed strong transduction in the intended region and virtually no leakage into off-target areas.

Why This Matters for Seizure Disorders

Seizures commonly arise from hyperactive clusters of neurons, often located in specific regions such as the hippocampus. Traditional anti-seizure medications circulate throughout the body and brain, which can lead to wide-ranging side effects and limited effectiveness. Surgical removal of seizure-forming tissue is possible in some patients but carries significant risks.

This new method allows researchers to precisely modulate the relevant neural circuit while avoiding unwanted effects on healthy brain areas. According to the team’s findings, the targeted neurons responded strongly to the chemogenetic drug, resulting in a measurable increase in seizure threshold in the animal model—meaning a seizure became harder to induce.

Another major advantage is that this treatment can be triggered on demand. Patients would not experience constant suppression of neuronal activity; instead, they could take a drug during periods when they are more vulnerable to seizures. Over time, this approach might be tuned to individual needs, improving outcomes while reducing side effects associated with continuous medication.

Because both focused ultrasound brain-barrier opening and viral gene delivery are already being tested in early clinical trials for other neurological conditions, the path toward adapting ATAC for human studies may be faster than if all three components were entirely new technologies.

Additional Technologies Developed by the Same Research Group

The study also references complementary methods from the same laboratory. One notable tool is REMIS, or Recovery of Markers through Insonation, a technique that uses focused ultrasound to release engineered or natural proteins from a specific brain region back into the bloodstream. This allows researchers to monitor gene expression or molecular changes in a noninvasive way. REMIS has already progressed into a clinical trial with collaborators at the Texas Medical Center, Baylor College of Medicine, and MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Together, the team envisions a full ultrasound-based platform:

• one method to deliver genetic tools

• another to modulate brain circuits

• and another to measure outcomes from the same targeted region

Such a setup could allow clinicians to diagnose, treat, and track neurological conditions with unmatched precision.

Broader Context: Focused Ultrasound in Neuroscience

Focused ultrasound is gaining momentum in multiple areas of brain research. It offers the ability to reach deep brain structures without cutting through the skull. At low intensities, it can safely open the blood-brain barrier for therapeutic delivery. At higher but still controlled intensities, it can stimulate or suppress neural circuits. The precision of these beams—often just a few millimeters wide—makes it ideal for targeted interventions.

Clinical trials are currently evaluating focused ultrasound for conditions including Alzheimer’s disease, glioblastoma, Parkinson’s disease, and essential tremor. One of the biggest challenges has been combining ultrasound with treatments that require access past the blood-brain barrier; the ATAC method neatly addresses this by pairing ultrasound with gene delivery and a controllable chemogenetic switch.

Broader Context: Gene Therapy and Chemogenetics

Gene therapy for the brain has advanced rapidly thanks to improved viral vectors that can target specific neuronal populations with fewer side effects. The AAV (adeno-associated virus) vectors designed by the Rice team are customized for efficient entry during ultrasound-opened BBB windows.

Chemogenetics, meanwhile, allows researchers to design receptors that respond only to certain lab-created or modified drugs. In this case, the inhibitory receptor allows neurons to reduce their firing rate when the activating drug is present.

The combination of these tools with ultrasound creates a pathway toward noninvasive, selective, and timed neuromodulation, which is something no current therapy can fully achieve.

What Comes Next

Although the technique is promising, it is still experimental and has only been demonstrated in mice. Several steps are needed before clinical use becomes realistic:

• Larger-animal studies to test safety and precision

• Long-term tracking of viral expression and immune response

• Optimization of drug delivery for human pharmacology

• Regulatory evaluation of combining ultrasound, viral gene therapy, and chemogenetic drugs

Despite these challenges, this line of research provides a clear proof-of-concept for what many neuroscientists consider the future of precision neuromodulation.

Research Paper:

Nonsurgical Control of Seizure Threshold with Acoustically Targeted Chemogenetics

https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00404