New Study Reveals a Shared Brain-Gene Pattern Behind Autism Symptom Severity in Children With Autism and ADHD

A new research study published in Molecular Psychiatry has uncovered something genuinely intriguing about the biology of autism and ADHD. Instead of drawing strict lines between these two neurodevelopmental conditions, the study suggests that certain brain-gene patterns linked to autism symptom severity show up across children diagnosed with either autism or ADHD. This is a big deal because it shifts the conversation from diagnoses toward the underlying biology that shapes how children think, feel, and behave.

Below is a clear, straightforward breakdown of the findings, the methods, and why this study matters — along with a bit of additional background knowledge that helps put everything into context.

What the Study Looked At

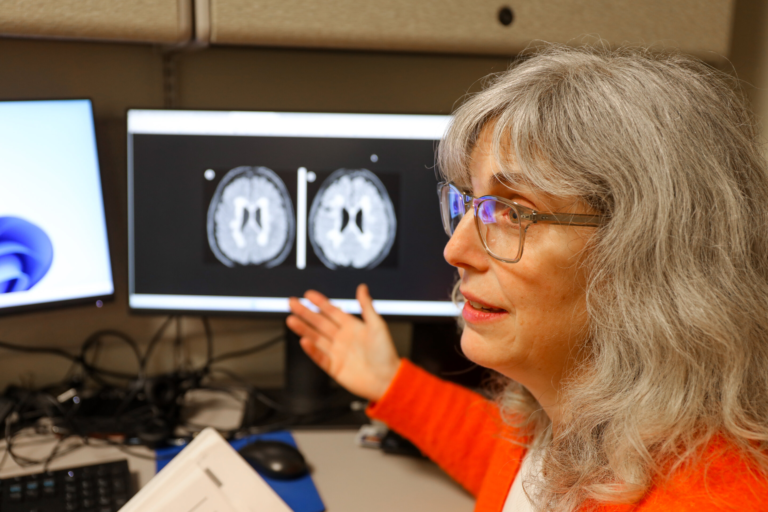

Researchers from the Child Mind Institute and partnering institutions examined 166 verbal children, all between 6 and 12 years old, diagnosed either with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or ADHD without autism. By deliberately including children from both groups, the team wanted to ask a crucial question: Are there biological features that track with autism symptoms even when the child doesn’t have an autism diagnosis?

To explore this, the team used resting-state functional MRI, a widely used technique for measuring how different parts of the brain communicate with each other while not performing any task. Brain-to-brain communication, also called functional connectivity, can reveal how strongly networks are linked — and whether those networks are maturing typically.

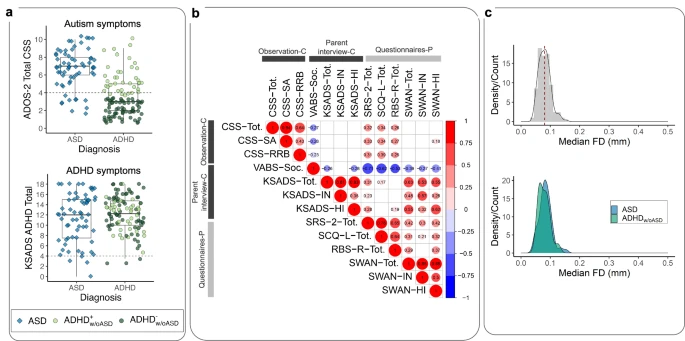

The researchers also assessed each child’s autism symptom severity using recognized clinical tools. Instead of pigeonholing children into diagnostic boxes, the study treated autism traits dimensionally, meaning it looked at severity on a spectrum.

After the brain scans were analyzed, the researchers took an extra, cutting-edge step: they used in silico spatial transcriptomic analysis. Basically, they compared the connectivity patterns they found with existing maps of where certain genes are active in the brain. This allowed them to see which genes were most related to the connectivity differences.

What the Researchers Found

One key result stood out: children with more severe autism symptoms — regardless of whether they had an autism diagnosis or an ADHD diagnosis — showed increased connectivity between the frontoparietal (FP) network and the default-mode (DM) network.

This is important because both of these networks are heavily involved in functions that are central to autism:

- The frontoparietal network deals with executive function, such as flexible thinking, switching attention, and organizing actions.

- The default-mode network is connected to social cognition, internal thoughts, and self-referential thinking.

In typical development, the connection between these two networks decreases as the brain matures. This thinning connection supports the brain’s ability to specialize and gives children better control over attention, social thinking, and problem-solving.

But in children with more severe autistic traits, this connection remained stronger than expected, suggesting atypical maturation.

This pattern didn’t depend on whether the child had an autism diagnosis or ADHD — meaning the biology of autism traits might cut across current diagnostic labels.

Another significant discovery came from the gene-mapping step. The connectivity differences overlapped with the expression of genes involved in neural development, especially genes already linked to both autism and ADHD. That means the brain patterns aren’t random — they’re tied to known genetic mechanisms that help shape how networks develop.

The study also emphasized that while autism symptom severity mapped onto specific brain-gene patterns, ADHD symptom severity did not show the same connectivity relationship. This reinforces the idea that although autism and ADHD frequently co-occur, the neural pathways associated with autism traits are distinct — yet still present in a subset of children diagnosed with ADHD.

Why These Findings Matter

This research supports a growing movement in neuroscience and psychiatry that favors dimensional rather than strictly categorical models of mental health. Instead of focusing only on diagnoses, researchers are increasingly looking at the specific traits a child has — and the underlying biology of those traits.

Some children diagnosed with ADHD show behaviors resembling autism but do not meet full criteria for autism. This study provides biological evidence to back up what many clinicians have observed for years: there may be shared neural and genetic roots behind these overlapping traits.

Here’s what this could mean moving forward:

- More accurate understanding of neurodevelopmental overlap

The study helps explain why some ADHD-diagnosed children exhibit autism-like behaviors. It’s not just coincidence — it may reflect shared biological pathways. - Improved diagnostic clarity

Instead of relying solely on behavioral labels, clinicians may increasingly incorporate brain-based or gene-related markers to understand a child’s needs. - Personalized support strategies

If neural profiles differ child-to-child, treatment approaches — whether behavioral therapy, executive-function training, or social-skills interventions — can be tailored more precisely. - Future biomarker development

The combination of neuroimaging and spatial gene mapping could eventually lead to objective biological indicators that help identify autism traits early.

Understanding the Brain Networks Involved

To give extra context, here’s a bit more about the two networks at the center of the study:

The Frontoparietal (FP) Network

This network is like the brain’s task manager. It helps with actions such as:

- Planning

- Decision-making

- Adjusting behavior

- Managing attention

Atypical activity here is often seen in both autism and ADHD and may contribute to challenges with cognitive flexibility and organized thinking.

The Default-Mode (DM) Network

This network is more active when a person is:

- Thinking about themselves

- Daydreaming

- Imagining

- Reflecting socially

Differences in DM activity have been repeatedly linked to autism, especially in areas related to social understanding and self-referential thinking.

The study’s finding — stronger FP-DM connectivity in children with higher autism symptom severity — fits with existing theories that variations in the way these networks separate or cooperate may underlie some social and executive challenges in autism.

Why Gene Expression Matters

Genes guide how the brain develops, from forming new connections to pruning old ones. The fact that the brain regions showing altered connectivity overlap with genes important for neural development reinforces that the observed connectivity differences reflect meaningful developmental biology rather than random noise.

Some of these genes are already known to be associated with:

- Synapse formation

- Neural wiring

- Executive-function development

- Overlap between autism and ADHD risk pathways

This gives researchers a clearer map of how genes may translate into functional brain differences and, ultimately, into behavior.

What This Means for Future Research

The study helps build momentum for a more integrated, biology-first approach in studying neurodevelopmental conditions. The researchers emphasized that both dimensional models (examining the severity of symptoms) and categorical models (focusing on diagnoses) remain valuable — but studies like this show how much can be gained when we look beyond diagnostic boundaries.

This work may also influence large-scale initiatives like the Child Mind Institute’s Healthy Brain Network, which collects neuroimaging and behavioral data from thousands of children. These datasets can help confirm whether the patterns observed in this study hold across larger, more diverse populations.