New Discovery Reveals a Surprising External Switch That Powers Pain Signaling in the Nervous System

Researchers from Tulane University and eight collaborating institutions have uncovered a previously unknown signaling mechanism in neurons that could reshape how we understand pain—and how we treat it. The work centers on a newly identified way in which nerve cells activate pain pathways after injury, using a secreted enzyme that operates outside the cell rather than inside, which is where most known signaling enzymes normally work. This mechanism, centered on the enzyme vertebrate lonesome kinase (VLK), may open the door to safer and more targeted pain treatments, while also revealing insights into learning, memory, and synaptic plasticity.

The discovery was led by Matthew Dalva of Tulane University and Ted Price of the University of Texas at Dallas, alongside researchers from institutions including UT Health San Antonio, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Houston, Princeton University, University of Wisconsin–Madison, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and Thomas Jefferson University. Their findings were published in Science and represent one of the first clear demonstrations that phosphorylation—a process long recognized as crucial for regulating cellular functions—can also control interactions between proteins in the extracellular space.

At the core of the study is the observation that active neurons can release VLK into the space between cells. Once released, the enzyme modifies proteins on the surface of neighboring neurons. This modification essentially turns pain signaling on after an injury. What makes this remarkable is that the process happens outside the cell, avoiding many of the complexities and risks associated with manipulating intracellular pathways.

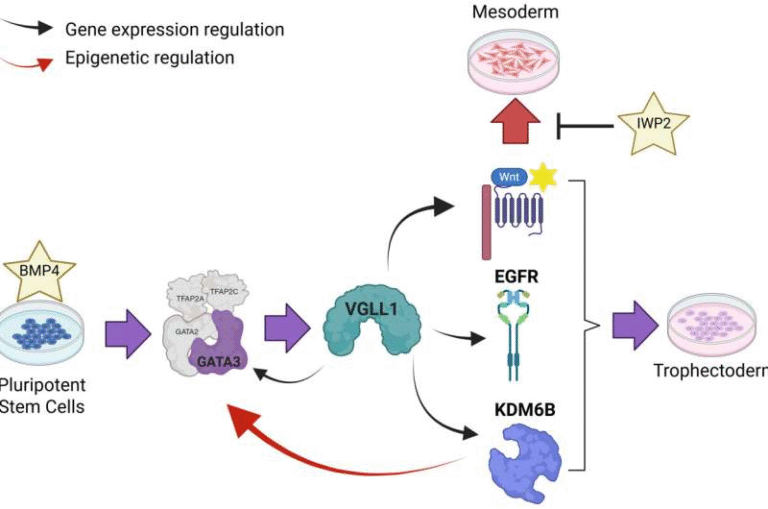

To explore VLK’s function, the researchers examined how it interacts with a receptor pair central to both pain processing and learning: EphB2 and the NMDA receptor (NMDAR). Under normal conditions, these receptors help regulate communication between neurons. But when VLK is released, it enhances how these receptors work together, strengthening signaling in a way that amplifies pain sensitivity.

Experiments in mice highlighted the importance of this mechanism. When VLK was removed from pain-sensing neurons, mice did not develop the usual heightened pain response after surgery. Importantly, they still moved normally and responded to regular sensory input, which suggests that VLK specifically affects injury-induced pain rather than general sensation or motor function. When additional VLK was introduced, the opposite happened: the mice displayed stronger pain responses.

This specificity matters. Many existing drug targets, such as NMDA receptors themselves, are involved in numerous essential brain functions. Blocking them often leads to unacceptable side effects. Targeting VLK, however, might allow drug developers to influence pain pathways directly at the extracellular interface, eliminating the need for drugs to penetrate neuron interiors. Because of this, VLK offers an avenue for creating safer analgesics that avoid the common pitfalls of current treatments.

The researchers also noted that VLK’s secretion depends on normal neuron activity and that it can modify only a select group of proteins, the most important being EphB2. Once exposed to VLK, EphB2 becomes more likely to interact with NMDARs, reinforcing synaptic strength. This mechanism provides one of the first examples of how modifying proteins outside the cell can guide changes inside synapses.

Since EphB2-NMDAR interactions are heavily involved in learning and memory, this finding has implications far beyond pain research. It raises the possibility that extracellular kinases like VLK play a broader role in shaping how synapses adapt, learn, and store information.

What Makes Extracellular Signaling Important?

Most enzymes that regulate signaling pathways work inside cells. They rely on entering the cell, binding to internal scaffolds, and modifying intracellular proteins. But entering cells is a major barrier for many drugs. Delivering molecules that can safely interact with intracellular targets is extremely difficult, especially in the brain, where the blood–brain barrier keeps most substances out.

An extracellular kinase like VLK simplifies many of these challenges. A drug that modifies VLK or interferes with its interaction with cell-surface proteins could, in theory, avoid the need for complex delivery systems. Such a drug may reduce pain sensitivity without interfering with other essential neural functions.

This represents an emerging trend in neuroscience: a shift toward extracellular modulation. By studying how cells influence one another at their surfaces, researchers hope to develop therapeutics that work more selectively and with fewer systemic effects.

Why This Research Matters for Pain Science

Chronic pain affects millions worldwide, and many of the most effective treatments come with well-known risks. Opioids cause addiction, tolerance, and overdose potential. Anti-inflammatory medications can harm organs. Meanwhile, drugs targeting NMDA receptors can cause cognitive disturbances and neurotoxicity if not precisely controlled.

By identifying VLK as a key switch in pain amplification, scientists now have a way to target pain at its source without interfering with general sensory function. Since removing VLK did not affect heat or chemical pain responses, the mechanism seems particularly tied to mechanical hypersensitivity, the form of pain that often arises after surgery or injury.

This also may lead to new insights about post-surgical pain, neuropathic pain, and other forms of heightened pain sensitivity that current medications often struggle to manage.

A New Layer to Synaptic Plasticity

The discovery also challenges traditional views of synaptic plasticity—the brain’s ability to change and adapt. Learning and memory require adjustments in communication between neurons, and NMDARs and EphB receptors have long been known to participate in these processes.

VLK adds a new external regulatory step, showing that synaptic strength isn’t just controlled from inside the cell but can also be tuned from the outside. This broadens our understanding of how neurons negotiate connections and may eventually connect to research in cognitive enhancement or recovery from neural injury.

What Comes Next?

The researchers emphasized that the next steps involve exploring how widespread VLK’s influence is. Does it modify only a small set of proteins, or is it part of a bigger, underappreciated biological system? If VLK is one of many extracellular kinases, scientists may need to rethink how cells communicate generally.

Additionally, drug developers will need to determine how to safely and selectively regulate VLK—either by blocking its release, preventing its binding to receptors, or designing molecules that interfere with its phosphorylation activity.

The involvement of multiple major research centers underscores the significance of this work. By combining expertise in synaptic biology, molecular neuroscience, and pain science, the collaborative team was able to identify a mechanism that has implications across species and across multiple fields of study.

Research Reference

The synaptic ectokinase VLK triggers the EphB2–NMDAR interaction to drive injury-induced pain (Science, 2025)

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adp1007