RNA Editing Study Reveals How Individual Neurons Gain Unique Identities

A new study from MIT has mapped out, in remarkable detail, how neurons that start from the same DNA can still diverge in meaningful ways thanks to RNA editing. This research, done in fruit fly motor neurons, overturns several long-held assumptions and reveals a much more dynamic landscape of RNA modifications than scientists previously understood. It also opens the door to discovering new editing enzymes and exploring how RNA edits influence neural development, behavior, and even disease.

How the Study Was Done

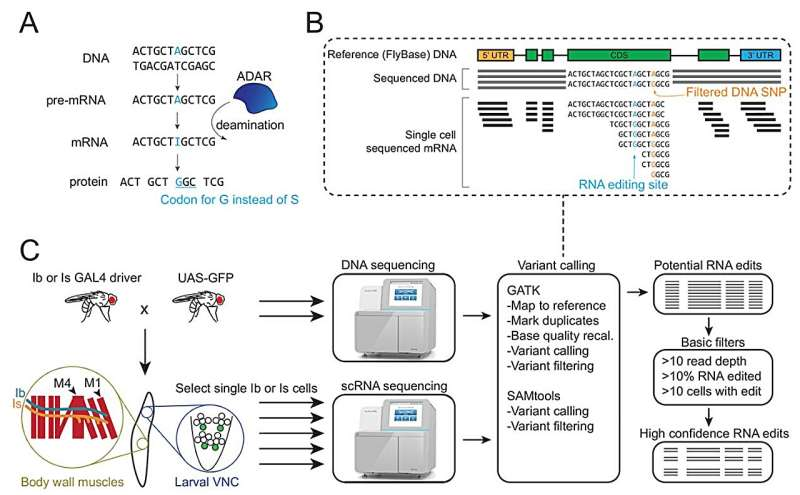

Researchers examined more than 200 individual motor neurons from fruit fly larvae—specifically tonic (Ib) and phasic (Is) glutamatergic motoneurons, which are widely used in neuroscience as models for basic neural function. Using single-cell sequencing techniques, the team compared each neuron’s RNA to the underlying DNA sequence to identify places where RNA had been edited after transcription.

RNA editing, particularly A-to-I editing carried out by the well-studied enzyme ADAR, can change the way proteins are built or regulate how much protein is produced. This makes it a powerful mechanism for fine-tuning neuronal activity.

What the researchers found was far more complex and varied than previous studies—mostly in mammals—had suggested.

What the Scientists Found

From roughly 15,000 genes in the fly genome, neurons collectively showed hundreds of edits across a wide range of transcripts. Specifically, the study identified:

- 316 canonical ADAR-based editing sites across 210 genes

- 175 of these sites located in protein-coding regions

- 60 edits predicted to significantly alter amino acids

- 141 editing sites in non-coding regions that affect transcript regulation rather than protein content

The researchers also found many non-canonical edits—changes that ADAR did not make. This is important because it suggests the existence of other editing enzymes that biology has not yet fully mapped out. Understanding these enzymes could expand future genetic therapy approaches, including potential ways to repair broken proteins associated with human diseases.

Editing Rates Were Not What Anyone Expected

One of the most surprising findings was the wide variation in editing rates across individual neurons.

Earlier animal studies suggested RNA editing tends to occur in a binary manner—either almost always or almost never. But in this dataset:

- The average editing rate per site was around two-thirds

- The majority of edits occurred in the 20% to 70% range

- 27 sites in 18 genes were edited over 90% of the time

Even more striking, neurons of the same type sometimes behaved very differently. A site that one neuron edited 100% of the time might be completely unedited in another neuron of the same subtype. This suggests a stochastic, or probabilistic, editing process that contributes to the individuality of neurons.

The researchers also saw that the more highly a gene was expressed, the less editing it tended to undergo. This implies that enzymes like ADAR may simply reach a saturation point—they can only edit so many transcripts before being overwhelmed.

Why These Edits Matter

Many of the most heavily edited genes are key players in neural communication, including:

- Genes involved in neurotransmitter release

- Ion channels regulating electrical properties of neurons

- Proteins that influence synaptic strength

One previously studied example is Complexin, a protein that restrains the release of glutamate. In an earlier MIT study, researchers found that just two edits in Complexin produced eight different protein versions, each with measurable effects on synaptic current. The new study has now identified 13 additional edits in this gene that remain uncharacterized.

Another especially interesting target is Arc1, a gene critical for synaptic plasticity—the ability of neurons to strengthen or weaken connections during learning. Arc1 underwent a non-canonical edit, and notably, this editing is absent in fruit-fly models of Alzheimer’s disease. This connection raises questions about whether changes in RNA editing patterns may contribute to synaptic decline in neurodegeneration.

The researchers are now exploring how the dozens of newly documented edits impact neuron function at the molecular and circuit levels.

Developmental Insights from Juvenile Neurons

Because the study examined larval neurons, the team discovered many edits that appear to be specific to developing brains rather than adult ones. This suggests RNA editing may serve different roles across the lifespan—possibly guiding early neural wiring before refining neural activity later on.

It also means past adult-focused studies may have overlooked a substantial portion of developmental RNA editing dynamics.

Why RNA Editing Diversity Matters in the Bigger Picture

RNA editing provides a way for neurons to gain unique identities without any changes to DNA. This is especially important in the nervous system, where genetically identical cells must take on highly specialized roles. RNA editing allows for:

- Fine control over ion channel properties

- Adjustment of neurotransmitter release

- Modulation of synaptic strength

- Adaptation to neural activity

If every neuron had identical RNA and protein content, neural circuits would be far less flexible. Editing introduces subtle differences that can shape how neurons behave, respond to stimuli, and interact with each other.

As scientists explore the full landscape of these edits, they may uncover new ways RNA editing contributes to:

- Learning and memory

- Developmental disorders

- Neurodegenerative diseases

- Individual differences in behavior

Additional Background: How RNA Editing Works

RNA editing typically happens when enzymes modify nucleotides in RNA transcripts.

The main forms include:

- A-to-I editing (adenosine to inosine): carried out by ADAR enzymes, the most common and best understood.

- C-to-U editing: much rarer and usually associated with other enzyme families such as APOBEC.

When edits occur in protein-coding regions, they can alter the amino acid sequence. When they occur in non-coding regions, they may affect:

- RNA stability

- Translation efficiency

- Splicing

- Localization within the cell

Stochastic editing—where the same site is edited at different rates in different cells—adds another level of variation. This randomness may serve as a biological mechanism for generating diversity among neurons, helping brains adapt and evolve.

Why Fruit Flies Are Valuable for This Research

Fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) are ideal for RNA editing studies because:

- Their genome is compact and well-mapped.

- Their neurons share key functional similarities with human neurons.

- Genetic tools allow extremely precise manipulation.

- Their development is fast, making it easy to compare stages.

Many discoveries about neurons, synapses, and behavior first emerged from fruit-fly research before being later confirmed in mammals.

Final Thoughts

This study provides one of the most detailed looks ever at RNA editing within individual neurons. Rather than a simple, binary system, RNA editing turns out to be a rich, variable, and dynamic process that may help explain how neuronal diversity arises and how neural circuits achieve such incredible complexity.

As researchers continue investigating both canonical and non-canonical edits, we may uncover new mechanisms behind learning, memory, development, and disease—and new therapeutic strategies that manipulate RNA editing to fix broken genes or restore neural function.

Research Link:

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.108282.2