Dopamine Desensitization in Fruit Flies Reveals Why Repeated Experiences Lose Their Appeal

New research published in Nature Neuroscience offers a detailed look at how the brain naturally downgrades the appeal of repeated behaviors, using fruit flies as the model. The study focuses on how dopamine, a key neurotransmitter involved in motivation and reward, gradually becomes less effective after repeated actions. This reduced effectiveness happens because the D2 dopamine receptor (D2R) becomes desensitized, meaning it stops responding as strongly as it did during earlier experiences.

This same mechanism is widely known in the context of drug addiction, where people need increasingly higher doses to achieve the same effect. What’s striking about this new work is that the researchers found a natural, everyday use for this mechanism—it helps organisms shift away from repeated behaviors once the novelty wears off. This establishes desensitization as an important biological tool, not just a pathological consequence of drug use.

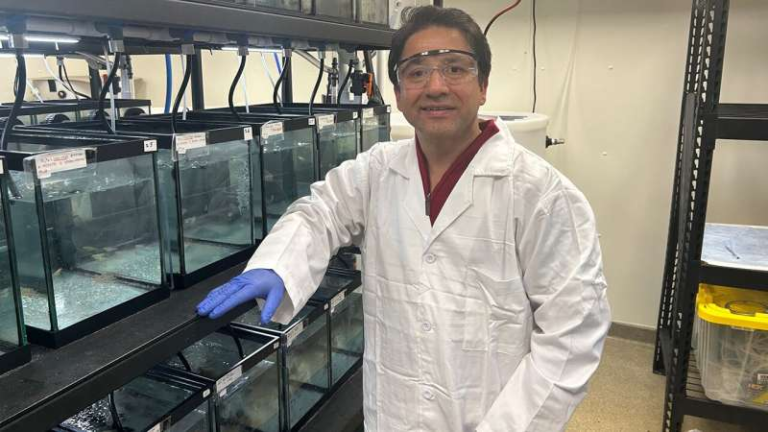

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital, led by Michael Crickmore, used male fruit flies to explore this process. Fruit flies are particularly useful for reward and motivation research because their neural circuits are simple enough to study with precision while still sharing fundamental properties with more complex organisms.

How the Researchers Studied Motivational Fatigue

The focus was on mating behavior, one of the most robust natural rewards in animals. Male fruit flies will typically persist in mating even when mildly threatened. This persistence is supported by dopamine signaling through the D2R in specific neural circuits responsible for mating decisions.

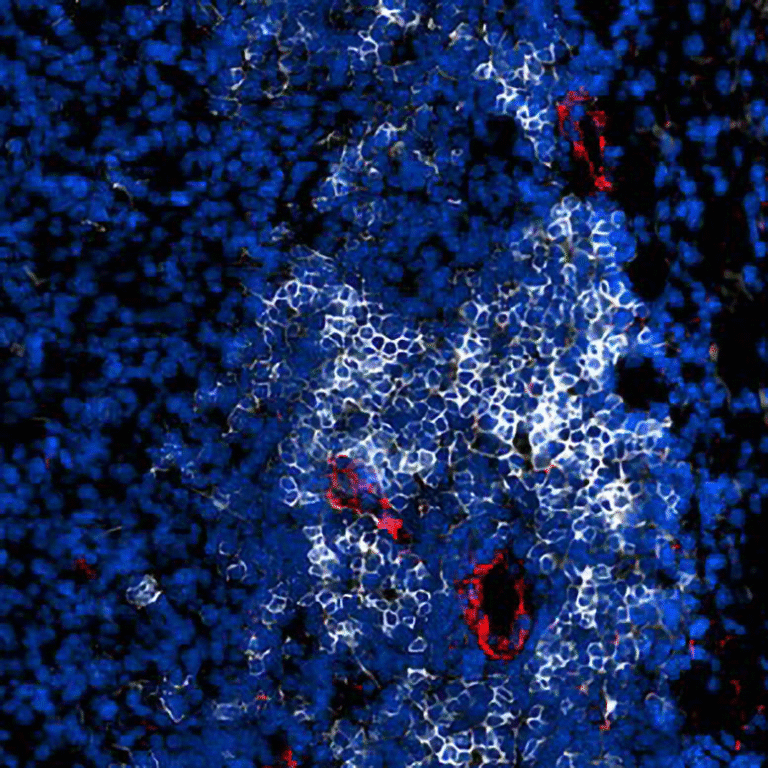

To see how repetition affects motivation, the scientists allowed males to mate multiple times. Over time, they observed that the flies became increasingly willing to abandon mating when challenged. The rewarding behavior no longer held the same motivational weight. Importantly, dopamine release itself did not decrease. Instead, the receptors receiving the dopamine signal became less sensitive.

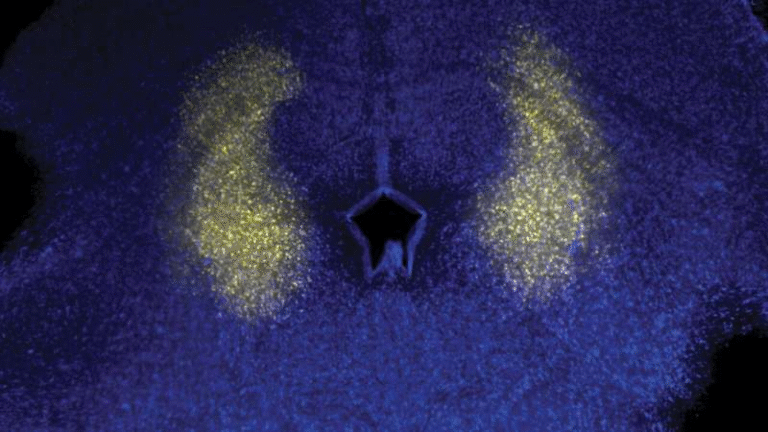

This desensitization occurred specifically in the neural population known as copulation decision neurons (CDNs). These neurons decide whether the fly should continue or abandon mating based on environmental cues. Early in the mating sequence, dopamine strengthens the fly’s resolve. After several matings, however, the D2R receptors on these neurons had become desensitized, meaning dopamine could no longer suppress the quitting signal effectively.

The team found that this desensitization is driven by a β-arrestin–dependent mechanism. β-arrestin is a protein known for its role in reducing receptor sensitivity after repeated activation. When the researchers genetically interfered with β-arrestin in the CDNs, the flies did not lose motivation after repeated matings. They continued to behave as if each mating was their first—persistent, resilient, and difficult to interrupt.

This shows that the decreasing appeal of a behavior after repetition is not from fatigue or depletion but from a deliberate biological adjustment, one that helps regulate how much energy and time an organism spends repeating the same action.

Why This Natural Desensitization Matters

The discovery is important because it demonstrates that the brain uses desensitization not just as an unfortunate side effect of drug exposure but also as a normal process for managing motivation. In daily life, people experience something similar: the first ride on a rollercoaster is thrilling, the twentieth ride—not so much. This decline in excitement may be partially explained by the same kind of receptor desensitization that happens in the fruit flies.

The researchers believe this mechanism helps prevent animals from becoming overly fixated on a single behavior when better opportunities might require attention. By locally adjusting sensitivity in the circuits controlling a specific action, the brain can devalue one behavior while keeping motivation intact for others. This preserves behavioral flexibility, which is essential for survival.

In contrast, drug addiction causes widespread D2R desensitization. Instead of devaluing one repeated behavior, it leads to the devaluation of all natural rewards, leaving the drug as the only stimulus capable of triggering significant dopamine-driven motivation. This insight hints that addiction may be an exaggerated form of a useful natural process, rather than a wholly separate phenomenon.

Understanding this relationship could help reframe how motivational disorders are studied. For example, conditions involving loss of interest, burnout, or anhedonia may have ties to improper regulation of receptor sensitivity in specific brain circuits. This study encourages scientists to explore whether targeted manipulation of receptor desensitization could restore healthy motivation patterns without globally altering dopamine levels.

More About Dopamine, D2 Receptors, and Behavioral Regulation

Because this study touches on fundamental aspects of neuroscience, it’s helpful to look more closely at how dopamine and the D2 receptor typically operate.

Dopamine’s Role in Motivation

Dopamine is not just the “pleasure chemical”—a common misconception. Instead, it helps track value, predict outcomes, and reinforce actions that lead to good results. When dopamine communicates effectively, organisms are more motivated to repeat rewarding tasks.

What Makes D2R Important

The D2 receptor often acts as a regulatory checkpoint. While some dopamine receptors encourage activation, D2R can modulate or fine-tune signals. Its sensitivity level determines how strongly an organism feels compelled to continue an activity.

When D2R becomes desensitized, it requires more dopamine to achieve the same effect, lowering motivation for the associated behavior.

Why Desensitization Exists

In natural settings, desensitization is useful because no animal should commit unlimited time to one repeated behavior. Even rewarding actions need to taper off to allow other important activities—feeding, exploring, social interaction, and avoiding danger.

This makes desensitization a built-in behavioral balancing system that modulates long-term motivation.

Implications for Broader Research

Because the same type of desensitization happens in mammals, including humans, this fruit fly study may inspire new directions in research on:

- Addiction mechanisms

- Chronic motivational fatigue

- Compulsive behaviors

- Anhedonia and depression

- Behavioral flexibility and decision-making

Understanding the localized desensitization of D2R may help scientists develop targeted interventions that adjust specific behavior-related circuits without disturbing dopamine function across the entire brain.

This could lead to more precise treatments, less dependence on global dopamine-boosting drugs, and better insight into how our drives and interests naturally rise and fade.

Research Reference

Behavioral devaluation by local resistance to dopamine (Nature Neuroscience, 2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-025-02079-x