Computer Model That Detects Hidden Drug-Resistant Infections Shows Major Advantages Over Traditional Hospital Contact Tracing

A new study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health presents an analytical tool that may significantly strengthen hospitals’ ability to control the spread of antibiotic-resistant infections. Instead of relying solely on traditional methods like contact tracing, this new framework uses multiple data sources to detect asymptomatic carriers—patients who carry dangerous bacteria without showing symptoms and who are therefore invisible to standard surveillance. The research, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates that this approach can outperform existing strategies in reducing both infections and colonization within hospital settings.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) continues to be one of the world’s most pressing health threats. In 2019 alone, an estimated 5 million deaths were associated with AMR infections globally. Hospitals, in particular, face ongoing challenges from resistant organisms that spread quietly and quickly, often through individuals who never develop symptoms. Because routine clinical practice does not typically include screening for many of these organisms, these silent carriers can unknowingly transmit pathogens to patients, staff, and even people in the surrounding community.

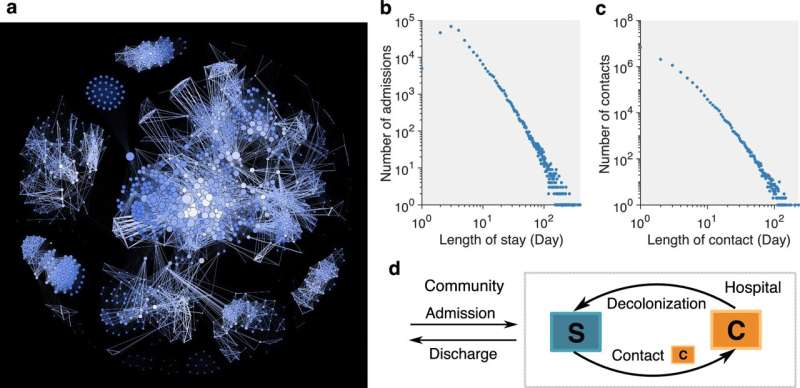

The Columbia team’s new inference framework was designed specifically to address this gap. It is the first method to combine patient mobility data, clinical culture tests, electronic health records, and whole-genome sequencing to track and predict the spread of an antimicrobial-resistant organism. By integrating these four streams of information, the model can estimate, with much higher accuracy, which patients are likely to be carrying resistant bacteria—even when test results are missing or limited.

To test the tool, the researchers used five years of real-world data from a major New York City hospital. Their focus was carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP), a pathogen known for its high mortality rate and ability to survive in hospital environments. Levels of CRKP colonization vary by health-care setting, but some facilities show colonization rates reaching up to 22% of patients. Because hospitals do not routinely screen for CRKP, many colonized individuals go unnoticed, enabling the pathogen to spread.

Using the integrated data sources, the framework modeled how CRKP moved from person to person over time. It was able to identify potential carriers much more effectively than methods based on simple factors such as a patient’s length of stay, the number of contacts they had, or whether any of their contacts had tested positive.

Importantly, the study also simulated how hospital outcomes would change if these inferred carriers were isolated. The results showed a clear advantage over standard contact-tracing approaches. According to the analysis, isolating 1% of patients—about 10 to 13 individuals per week—using the new model reduced 16% of positive cases and 15% of colonization events. When 5% of patients (roughly 50 to 65 individuals per week) were isolated, the reductions increased to 28% of positive cases and 23% of colonization.

In contrast, traditional contact tracing, which typically focuses only on close contacts of known positive patients, produced smaller improvements. Under the same conditions, isolating 1% of patients reduced just 10% of positive cases and 8% of colonization, while isolating 5% resulted in 20% and 16% reductions, respectively. These differences indicate that hospitals may be able to control resistant pathogens more efficiently by identifying carriers proactively rather than reactively.

This study builds on earlier research from 2021, also led by Columbia researchers, which demonstrated that a network-based approach could more accurately infer colonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) than older methods. The new work represents a major step forward because it incorporates electronic health records and genomic sequencing, offering far more precise insights into transmission pathways and hidden carriers.

However, even with these improvements, the researchers acknowledge that eliminating antimicrobial-resistant organisms from hospitals remains difficult. AMR pathogens often circulate widely in the community, which means hospitals do not control the inflow of colonized individuals. Additionally, routine culture tests have high false-negative rates, and surveillance systems across institutions vary widely in quality. The authors suggest that future research may involve ultra-dense genome sequencing, which could help reveal even more subtle patterns of spread.

The study was part of a collaboration involving computational scientists and clinical experts from several medical centers. Contributors included researchers from Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the University of California San Francisco, and New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

Understanding Why Asymptomatic Carriers Matter

Asymptomatic colonization plays a central role in the spread of AMR organisms. Many bacteria, including CRKP, can live harmlessly in the gut without causing illness. A person may feel completely healthy yet shed bacteria during routine medical care, transfers between wards, or contact with surfaces and equipment. Because these individuals do not meet the usual criteria for testing, they rarely appear in surveillance data.

This hidden spread is what makes AMR outbreaks so challenging to control. Hospitals traditionally depend on detecting symptomatic cases and then tracing their contacts. But if most transmission is happening silently, then the majority of carriers never get screened, and crucial links in the chain of infection remain invisible.

That is why a data-driven inference model is so appealing: it does not rely solely on confirmed positives. Instead, it examines patterns in movement, interactions, clinical risk factors, and genetic relationships between isolates to estimate who is likely colonized, even without a lab test.

Why Whole-Genome Sequencing Makes a Difference

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) allows researchers to examine the genetic makeup of bacterial isolates to determine how closely related they are. If two patients carry nearly identical strains, it suggests a recent transmission event. When integrated with mobility and EHR data, WGS helps reconstruct transmission chains more accurately than observational data alone.

In this study, even sparse genomic data—not every isolate was sequenced—meaningfully improved the model’s performance. This shows that hospitals do not need full sequencing coverage to benefit; partial sampling can still guide better decision-making.

Broader Implications for Hospital Infection Control

Hospitals worldwide are facing increasing pressure from AMR organisms such as CRKP, MRSA, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). These pathogens lengthen hospital stays, increase treatment costs, and contribute to higher mortality rates. Traditional infection-control strategies, while essential, have clear limitations when silent transmission dominates.

Tools like Columbia’s inference framework could help hospitals prioritize limited resources—such as isolation rooms, staff time, and diagnostic testing—toward the patients who pose the greatest transmission risk. This targeted approach may prove more effective than universal screening, which is costly and not always feasible.

Additionally, as more hospitals adopt electronic health records and improve their ability to track patient movement, models like these could become easier to implement. Genomic sequencing is also becoming more affordable and faster, making integration into routine infection control increasingly realistic.

However, widespread adoption will require addressing challenges such as data privacy, interoperability of hospital IT systems, and training infection-control teams to use predictive analytics. Still, the potential benefits—reduced infections, fewer deaths, and improved patient safety—make this an area of growing interest in public health.

Research Reference

Inferring asymptomatic carriers of antimicrobial-resistant organisms in hospitals using genomic, microbiological and patient mobility data

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-65241-w