Robotic Testing Helps Reveal Hidden Sensory Loss in Stroke Survivors

Researchers at the University of Delaware have been digging into one of the most overlooked challenges in stroke recovery: the loss of proprioception, the body’s ability to sense movement and position. Their newest findings suggest that many stroke survivors may have sensory impairments that go undetected, simply because traditional assessments don’t catch them. Using a robotic exoskeleton, the research team has developed a more precise way to evaluate these deficits — without requiring the patient to move their affected arm at all.

A decade ago, a man named Don Lewis experienced this struggle firsthand. At age 55, he woke up unable to move the left side of his body after a stroke caused by an aneurysm. He eventually regained the use of his left leg after extensive rehabilitation, but his left arm remained paralyzed. Even today, he can still feel pain when the arm is bumped or scraped, but he cannot move it voluntarily. In the years since, Lewis has survived two additional strokes and continues working with researchers to make sense of how sensory loss affects recovery.

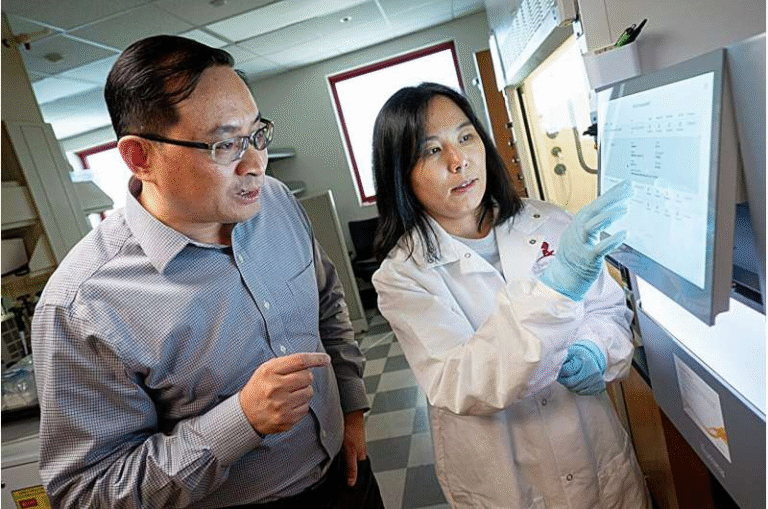

Inside Jennifer Semrau’s lab at the University of Delaware, Lewis participates in a series of tests using a KINARM robotic exoskeleton, a device designed to precisely track and control upper-limb movement. The goal is to understand the neural and behavioral factors behind sensory and motor recovery. The team specifically focused on proprioception — an area that remains under-examined in clinical settings, even though it plays a major role in everyday tasks like reaching, gripping, and coordinating movement.

To investigate this, the researchers used multiple robotic tests, including a new method called the single-arm measurement. In this task, the robotic device gently moves the stroke-affected arm while the participant uses their unaffected arm to signal whether they can feel the motion. This allows the researchers to measure the minimum amount of movement a person can detect. For someone without a stroke history, this threshold is often as small as half a centimeter. But in stroke survivors, the ability to sense movement can vary widely.

Some individuals cannot detect even 10 centimeters of passive arm movement — a difference large enough to affect basic safety and daily decision-making, such as recognizing whether a hand is near a hot surface or sharp object. These deficits occur because the communication between the brain and the receptors in the muscles — the ones responsible for signaling stretch and contraction — has been disrupted. While these receptors might still respond to physical changes, the brain may no longer effectively register the information, making coordinated movement difficult.

Interestingly, these sensory issues do not always align with motor issues. A person may be unable to move their arm voluntarily yet still have intact touch or pain sensation. Pain, for example, involves a different set of nerves than proprioception, so it can remain normal or even become more sensitive after a stroke. Meanwhile, touch can also increase or decrease depending on the individual. As Semrau explains, every stroke survivor has a unique combination of impairments — a reminder that sensory loss is far from uniform and cannot be predicted solely by motor ability.

One of the biggest challenges in clinical practice is separating sensory deficits from motor deficits, because the two systems interact so closely. If someone cannot move their arm, clinicians often assume the issue is motor-based, but without precise tools, it’s hard to determine whether sensory loss is also involved. The robotic assessments used in this study help isolate sensory ability by removing the need for voluntary movement entirely.

The research team includes doctoral candidate Joanna Hoh, an occupational therapist who became interested in sensory impairments during her work in stroke rehabilitation. In clinical environments, she noticed that treatment often focuses on restoring movement and strength, while sensory problems — especially those involving proprioception — are not routinely addressed. Her doctoral work aims to better understand sensory impairments and how they influence the daily activity levels of stroke survivors.

What the research team found is quite striking: in one of their broader studies, only 1% of clinicians reported that they regularly assess proprioception in stroke patients. Despite this, other studies have shown that without sensory recovery, full motor recovery is unlikely. Semrau and Hoh hope that creating reliable, accessible testing methods will encourage more clinicians to include sensory evaluations as part of standard stroke assessment. Their vision is a personalized medicine approach where therapy is tailored not only to motor deficits but also to the specific sensory impairments of each patient.

This study also contributes to a growing body of research showing that sensory and motor impairments should not be treated as separate issues. Understanding how these systems interact can lead to more effective rehabilitation strategies that support meaningful functional recovery. With more precise tools, clinicians may eventually be able to identify sensory problems earlier, customize rehabilitation plans, and potentially improve long-term outcomes for stroke survivors.

Understanding Proprioception: A Quick Guide

Since proprioception is at the center of this research, it’s worth exploring what it is and why it matters.

Proprioception is often described as the body’s sixth sense. It allows you to know where your limbs are without looking at them. For example, if you close your eyes and lift your arm, you don’t need visual confirmation to know it’s above your head. Receptors in your muscles and joints continuously send information to the brain about movement, pressure, and limb position.

When a stroke disrupts this system, a person may lose:

- The ability to sense where their arm is in space

- Awareness of joint angles

- The ability to detect small movements

- Confidence in making coordinated or precise movements

This can affect simple, everyday activities such as reaching for a cup, buttoning a shirt, or navigating a kitchen safely.

In rehabilitation, therapists often focus on visible motor issues, like weakness or reduced range of motion. But proprioceptive loss can be equally limiting, and without addressing it, progress in motor training may be slower or incomplete. Robotic systems, like the one used in this study, offer a new way to measure these deficits accurately and consistently.

Why Robotic Assessment Matters

Robotic devices such as the KINARM can precisely control limb movement and measure detection thresholds with accuracy that human clinicians cannot match. They also allow movements to be performed passively, which means the patient does not need to initiate or control the movement. This makes it possible to test sensory ability even in individuals with severe motor impairment.

Robotic tools provide several advantages:

- Objective measurement of movement detection thresholds

- Ability to test without requiring voluntary muscle activation

- High repeatability and consistency

- Identification of sensory impairments that traditional tests may miss

With technology like this, clinicians could better understand the full range of impairments after a stroke and create more customized treatment plans.

Reference

Proprioceptive Thresholds Are Indicators of Upper Limb Perception After Stroke (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1177/15459683251363245