Long-Term Calorie Reduction Shows Promise in Slowing Normal Brain Aging

A new long-term study from researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine has shed light on how consistent calorie reduction may influence the aging process inside the brain. The project, which began in the 1980s in collaboration with the National Institute on Aging, tracked the biological effects of eating 30% fewer calories over more than 20 years using a primate model closely related to humans. The results reveal notable cellular and molecular changes linked to healthier brain aging, especially in white matter regions that are essential for communication between different parts of the brain.

Understanding the Motivation Behind the Research

As the brain grows older, its cells experience metabolic stress, oxidative damage, and a decline in their ability to maintain the myelin sheath, the protective covering that insulates nerve fibers. When myelin begins to degrade, communication between neurons slows down, contributing to age-related cognitive decline. Additionally, microglia, the brain’s primary immune cells, tend to become chronically activated in aging and neurological conditions, leading to an inflammatory environment that can further harm brain tissue.

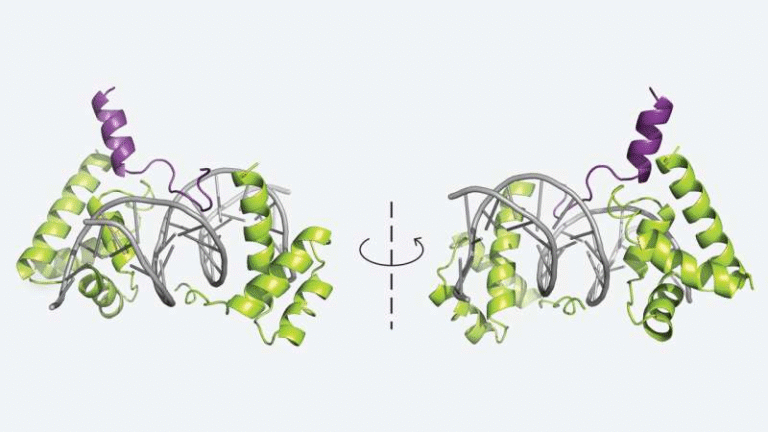

Credit: Aging Cell, 2025

Scientists have long known that calorie restriction can slow aspects of biological aging in various short-lived species, but evidence from long-lived animals—especially primates—has been limited. This new study provides some of the clearest long-term molecular-level data showing how dietary habits may influence brain health over decades.

How the Study Was Designed

The experimental model included two groups: one consumed a normal balanced diet, while the other consumed approximately 30% fewer calories but remained nutritionally supported. Both groups lived out their natural lifespans. Afterward, researchers examined their brains, focusing specifically on the white matter, where myelin-producing cells and immune cells are heavily involved in maintaining neural function.

To analyze how long-term calorie reduction influenced brain aging, the team relied on single nuclei RNA sequencing, a powerful technique that reveals the gene expression profiles of individual brain cells. Instead of looking at broad tissue samples, this method allows researchers to pinpoint precisely which cell types are affected by aging and how calorie restriction alters their molecular behavior.

What Researchers Found Inside the Brain

The findings show that brain cells from the calorie-restricted group were metabolically healthier and functioned more efficiently than those from the group that ate normally. Several key changes stood out:

- Oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce and repair myelin, displayed higher expression of myelin-related genes, suggesting stronger support for maintaining white matter integrity.

- These cells also showed enhanced activity in metabolic pathways such as glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis, both essential for generating the energy and raw materials required for myelin production.

- A specific subcluster of oligodendrocytes, referred to in the study as a CR synaptic OL subcluster, was associated with pathways critical for myelin synthesis, reinforcing the idea that calorie reduction directly influences cells responsible for neuronal insulation.

- Microglia, while naturally activated during aging, showed signs of a healthier immune profile in the calorie-restricted group, with reduced markers linked to chronic inflammation.

Altogether, these molecular patterns suggest that long-term calorie restriction supports better white matter maintenance, which could translate into slower brain aging at the cellular level.

Why These Findings Matter

The brain’s white matter plays a crucial role in coordinating communication between different neural regions. As white matter deteriorates, cognitive functions such as learning, memory, and processing speed tend to decline. If dietary habits can meaningfully influence how white matter ages, this opens the door to lifestyle-based strategies for promoting lifelong brain health.

The researchers emphasize that the results show how diet can shape the trajectory of brain aging. Long-term calorie reduction did not simply improve a narrow set of genes—it reshaped the broader molecular environment of some of the brain’s most essential support cells. While the study did not measure cognitive outcomes directly, the molecular evidence strongly suggests potential implications for learning and cognition.

Important Limitations to Consider

Even though the findings are promising, several limitations should be acknowledged:

- The study was conducted on primates, not humans. Although the species used is closely related to humans, results cannot be directly translated into dietary recommendations for people.

- Long-term calorie restriction is a significant intervention. Implementing a 30% reduction safely requires careful nutritional planning to avoid malnutrition.

- The research relied on postmortem tissue, meaning the researchers observed cellular changes but did not measure cognitive or behavioral performance during life.

- The sample size was limited, as is common in long duration primate studies.

Despite these limitations, the long-term nature of the research and the sophisticated analytical approach make the study highly valuable for understanding brain aging.

Additional Context: What We Know About Calorie Restriction in General

Calorie restriction has been studied for decades across a wide range of species. In rodents, worms, and flies, reducing calorie intake without causing malnutrition extends lifespan and slows biological aging. Benefits often include reduced inflammation, improved metabolic efficiency, enhanced stress resistance, and healthier cellular function.

In humans, long-term data is more limited. However, controlled studies such as the CALERIE trial have shown that moderate calorie reduction can improve metabolic health and slightly slow biological aging markers. Importantly, these human studies used much lower calorie reductions (around 12%) and shorter timescales (two years).

What remains unclear is how deep, decades-long calorie reduction affects human brain aging, especially since maintaining such a diet can be challenging and is not advisable without expert guidance.

Microglia and Myelin: Why They Matter

Two cell types highlighted in the study—microglia and oligodendrocytes—play essential roles in brain health.

Microglia act as the brain’s cleanup and immune response system. When chronically activated, they release inflammatory chemicals that can damage surrounding tissue. Reducing harmful microglial activation may therefore help preserve neural connections as the brain ages.

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for generating myelin. Because myelin is rich in fatty acids and energetically costly to produce, oligodendrocytes need strong metabolic support to function properly. The study’s observation that calorie restriction boosts metabolic pathways relevant to myelin production helps explain why white matter seems better preserved.

What This Means for Future Research

The study opens numerous avenues for further exploration. Scientists may now investigate:

- Whether specific nutrients or metabolic pathways can mimic the benefits of calorie restriction.

- How lifestyle factors—such as exercise or intermittent fasting—affect similar aging pathways.

- The possibility of targeting microglia or oligodendrocyte metabolic functions to slow cognitive decline.

Future work in humans will need to examine whether moderate, sustainable dietary adjustments can produce measurable improvements in brain aging markers.