New Immune Cell Discovery Could Transform How We Prevent Scar Tissue Buildup in Wounds

Researchers at the University of Arizona have identified a previously unrecognized population of circulating immune cells that appears to play a major role in fibrosis, the process that causes scar tissue to accumulate after an injury. This discovery offers a fresh angle on why scars form and opens the door to potential treatments designed to prevent or reduce fibrosis—something that currently has no FDA-approved therapies despite fibrosis being involved in nearly half of all deaths in developed countries.

Fibrosis shows up in serious conditions such as pulmonary fibrosis, renal fibrosis, liver disease including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, organ transplant rejection, and several forms of heart disease. The findings published in Nature Biomedical Engineering add important clarity to how the body heals and why the process sometimes goes wrong.

A Newly Identified Driver of Fibrosis

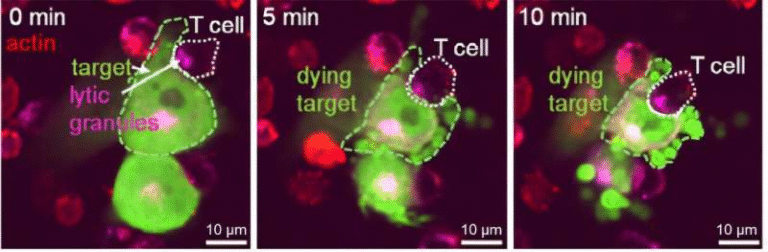

The research team, led by Kellen Chen and Geoffrey Gurtner, focused on immune cells belonging to the myeloid family—specifically monocytes and macrophages that circulate through the bloodstream. These cells were found to be mechanoresponsive, meaning they respond to physical forces such as tissue tension or strain during wound healing.

What makes this discovery significant is that these particular immune cells behave as primary drivers of fibrosis, not just passive participants in inflammation. The researchers found that:

- These cells become highly active during wound healing.

- Their signaling encourages the formation of dense, fibrotic scar tissue.

- Blocking the signals from these cells dramatically reduces scar formation.

This happened consistently in both mouse wound-healing models and human cell experiments, strengthening the case that these immune cells play a universal role in scarring across species.

Why Fibrosis Happens in the First Place

To understand the importance of this discovery, it helps to look at how normal wound healing works. After injury, the body follows a set sequence:

- Blood clotting stops the bleeding.

- Inflammatory cells move in to clean dead or damaged tissue.

- New cells grow, filling in the injured area.

- Remodeling occurs as the tissue reorganizes and strengthens.

When the system works perfectly, the tissue heals with minimal scarring. But when communication among immune cells, structural cells, and mechanical forces gets out of sync, the wound may produce excess collagen and fibrous tissue. This is fibrosis—essentially, the body overcorrecting and building a repair patch that becomes too rigid.

Despite its importance, scientists still don’t fully understand the later stages of wound healing, especially the transition from normal repair to pathological scarring. That gap is exactly what this new study helps close.

What the Study Found in Experiments

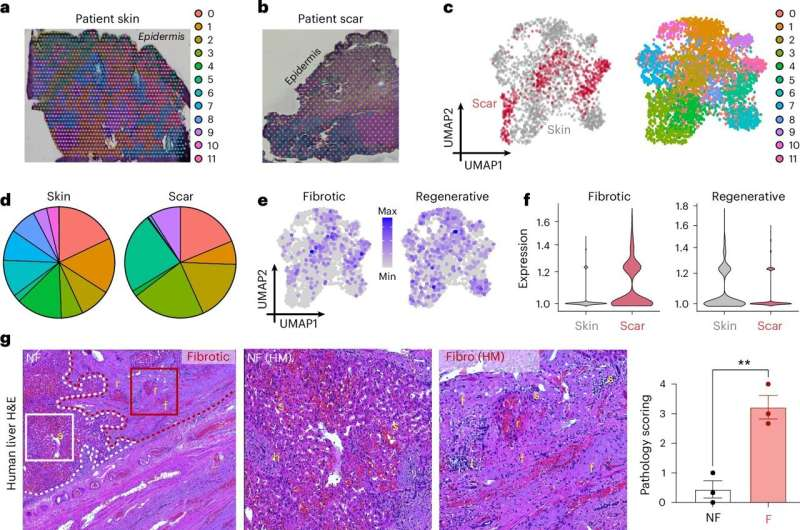

The researchers pinpointed a distinct population of myeloid cells that responds strongly to mechanical cues in a healing wound. These cells activate a signaling cascade that pushes the tissue toward fibrosis instead of normal regeneration.

Key observations include:

- When these mechanoresponsive immune cells were blocked, the resulting wounds displayed significantly less scar tissue.

- Interrupting their signaling restored the activity of anti-inflammatory cells normally involved in healthy healing.

- Human samples showed increased levels of these immune cells in both fibrotic skin and fibrotic liver tissue.

- Treated wounds produced thinner tissue with collagen that looked much more like normal skin architecture instead of dense scar fibers.

These results suggest that the immune system’s behavior under mechanical stress is far more important to fibrosis than previously recognized.

A Potential Therapeutic Strategy

The major takeaway from the study is the idea that fibrosis might be preventable by targeting immune cells that react to mechanical forces. This is a fresh direction in fibrosis research because scientists have historically focused on fibroblasts, the cells known for producing collagen. This study shifts the attention toward circulating immune cells that set the stage for fibroblast behavior.

If these mechanoresponsive cells can be controlled—perhaps by selectively blocking their signaling pathways—doctors could:

- Reduce scarring after surgery or injury.

- Slow or stop fibrosis in organs such as the liver, lungs, or heart.

- Potentially reverse fibrosis that has already begun.

The study suggests that fibrosis across different organs may share a common upstream trigger involving these immune cells.

Why This Discovery Matters So Much

Fibrosis is a leading cause of organ failure and chronic disability, and yet scientists have struggled to find a universal target for treatment. This research stands out because:

- It identifies a circulating cell population, meaning it could be accessible through the bloodstream.

- It reveals a mechanical-immunity connection, a concept that has recently gained interest in regenerative medicine.

- It proposes a consistent fibrosis mechanism across multiple organ systems.

- It points toward therapeutic strategies that may be more effective than targeting fibroblasts alone.

According to the researchers, this insight represents a paradigm shift in how fibrosis is understood and treated.

Additional Background: Understanding Immune Cells, Mechanosensing, and Fibrosis

To help readers get more context, here’s a deeper look at the components involved.

What Are Myeloid Cells?

Myeloid cells include monocytes, macrophages, and other immune cells originating from the bone marrow. They patrol the body, respond to infections, and support tissue repair. Their role in fibrosis has been suspected for years, but this study shows they may have a far more direct influence on scar formation than previously thought.

What Does Mechanoresponsive Mean?

A mechanoresponsive cell senses and reacts to physical forces. Tissue tension is a key driver in wound healing. For example, areas of the body under high tension—like the shoulders or chest—tend to scar more.

These immune cells appear to detect such tension and then switch into a pro-fibrotic mode, sending signals that increase collagen deposition.

Why Is Fibrosis So Dangerous?

While fibrosis might seem like just “scar tissue,” its consequences are vast. Excessive fibrosis can:

- Make organs stiff and unable to function properly.

- Lead to chronic diseases with no cure.

- Interfere with organ transplants.

- Cause disfigurement and pain.

Because fibrosis is involved in so many diseases, a breakthrough in controlling it could have far-reaching impacts.

What Comes Next for This Research?

The findings are promising, but they also raise several important questions for future work:

- Which signaling molecules are the best targets for drug development?

- Can treatments safely modulate these cells without compromising normal immune protection?

- Will blocking mechanoresponsive signaling work for chronic, long-established fibrosis?

- Are there biomarkers that can identify these immune cells early in disease progression?

Despite these questions, the study lays the groundwork for new research directions that could finally offer effective ways to manage or reverse fibrosis.

Research Paper Reference

Targeting circulating mechanoresponsive monocytes and macrophages to reduce fibrosis

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-025-01479-5