New Research Shows Sorbitol May Contribute to Liver Disease Even When Used as a Sugar Substitute

A new study has raised important questions about the long-held belief that sugar alcohols such as sorbitol are harmless alternatives to table sugar. Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis have discovered that sorbitol, a sweetener commonly found in “sugar-free” candies, gums, protein bars, and various processed foods, may behave far differently in the body than previously assumed. The findings reveal that sorbitol is only one metabolic step away from fructose, a sugar already known for its strong link to steatotic liver disease, a condition affecting almost 30% of adults worldwide.

This new work, published in Science Signaling, adds to a series of studies from the same research team showing how fructose metabolism can fuel cancer cells, worsen metabolic disorders, and contribute to liver fat accumulation. The new twist is that sorbitol can enter these same pathways — especially under certain dietary and microbiome conditions — and may pose risks when consumed in high amounts.

How Sorbitol Behaves Inside the Body

One of the study’s most striking findings is that sorbitol doesn’t need to come from food alone. The body can naturally produce sorbitol through an enzyme that converts glucose into sorbitol. This happens most notably when glucose levels are high.

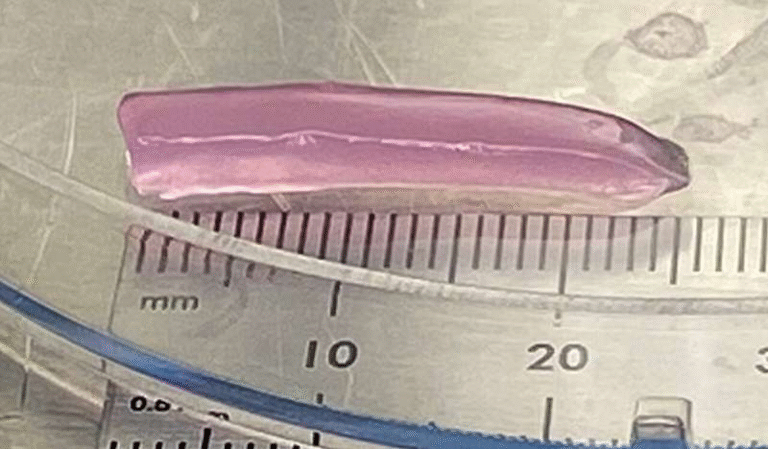

The researchers used zebrafish to demonstrate this process. After feeding, glucose levels in the gut rise high enough for the sorbitol-producing enzyme to activate. This was previously thought to be a mechanism mainly seen in diabetes, where chronically elevated glucose triggers sorbitol buildup. But the new research shows it can also occur in normal physiological settings.

Once sorbitol is produced, one of two things can happen:

- Gut bacteria may degrade sorbitol into harmless byproducts.

- If the right bacteria are missing — or sorbitol levels overwhelm them — sorbitol reaches the liver and is converted into a fructose derivative that promotes fat buildup.

The researchers emphasize that many metabolic “routes” can lead to fructose in the liver, and sorbitol is one of the major detours on that map.

Why Gut Bacteria Play a Critical Role

A key discovery in this study is the involvement of specific gut bacteria, particularly sorbitol-degrading Aeromonas strains. These microbes can break down sorbitol before it ever reaches the liver. When these bacteria are present, sorbitol is neutralized. When they are absent, sorbitol passes through the gut, enters the bloodstream, and eventually reaches the liver, leading to harmful effects.

This means sorbitol’s impact on liver health depends heavily on the composition and strength of an individual’s gut microbiome.

But even people with these protective bacteria may run into trouble if:

- They consume excessive glucose, causing increased internal sorbitol production.

- They consume too much dietary sorbitol, overwhelming the microbiome’s capacity to degrade it.

The researchers point out that gut bacteria can only do so much. Once sorbitol levels exceed what the bacteria can handle, the excess continues on its path to the liver.

Why This Matters for People Using Sugar Substitutes

Many people rely on sugar alcohols as “safer” alternatives to refined sugar, especially those with diabetes or metabolic concerns. Foods labeled as “sugar-free” or “low-calorie” often contain sorbitol because it provides sweetness without raising blood sugar dramatically.

But this study suggests that sorbitol may not be as harmless as once believed. High sorbitol exposure — whether internally generated or consumed — could contribute to the same liver problems associated with high fructose intake. The researchers found that sorbitol fed to animals spread into tissues throughout the body, challenging the assumption that polyols are simply excreted without consequence.

The lead researcher noted that even his own preferred protein bar contained unexpectedly high levels of sorbitol, highlighting how common it is in modern packaged foods.

Dietary Patterns That May Increase Risk

The findings suggest several scenarios where sorbitol exposure may become problematic:

- High glucose diets, which ramp up sorbitol production inside the gut.

- High intake of sorbitol-containing foods, such as sugar-free candies, low-calorie snacks, and some protein bars.

- Weakened or imbalanced gut microbiomes, which may occur after antibiotic use, illness, or poor diet.

- Frequent consumption of multiple sweeteners, which is increasingly common in today’s processed food landscape.

The research team stresses that sorbitol found naturally in fruits is present in modest quantities and is typically handled well by gut bacteria. The potential issues arise primarily when dietary or metabolic conditions push sorbitol exposure beyond what the microbiome can safely manage.

What This Means for Public Health

With fatty liver disease becoming one of the fastest-growing global health problems, understanding all dietary contributors is essential. Fructose has long been recognized as a major driver of liver fat accumulation. Now sorbitol — because it can be converted into fructose inside the body — may need to be re-evaluated.

The study warns that “there is no free lunch” when trying to replace sugar with alternative sweeteners. Diets heavy in sugar-free products may still stress the liver in unexpected ways.

This research also suggests that maintaining a healthy gut microbiome may be even more important than previously understood. Bacterial populations can dramatically change how the body processes sugars, sweeteners, and sugar alcohols.

Understanding Sorbitol and Other Sugar Alcohols

Sugar alcohols (also called polyols) include sorbitol, xylitol, erythritol, and others. They are widely used because they provide sweetness with fewer calories and smaller impacts on blood glucose. Sorbitol is naturally present in stone fruits such as peaches, plums, and cherries.

However, sorbitol has a unique metabolic profile:

- It sits chemically one step away from fructose, making conversion easy.

- The polyol pathway that converts glucose → sorbitol → fructose becomes more active when glucose is high.

- Some individuals produce sorbitol at higher rates due to metabolic or dietary factors.

- Digestive tolerance varies widely — excessive sorbitol is known for causing gastrointestinal upset.

This study suggests that the polyol pathway may also contribute to metabolic disorders when sorbitol overaccumulates and reaches the liver.

What Future Research Needs to Investigate

This study opens the door for many important questions:

- How do human gut bacteria compare to the sorbitol-degrading bacteria found in zebrafish?

- What levels of sorbitol intake become risky for humans?

- Could microbiome-based therapies — such as probiotics — help prevent sorbitol-induced liver stress?

- Are certain individuals (e.g., diabetics, people with dysbiosis, those on high-glucose diets) at higher risk?

- Do other polyols behave similarly when gut bacteria are overwhelmed?

Answering these questions will be essential before drawing firm conclusions for human health. Still, the current findings highlight a previously underappreciated link between diet, microbiome composition, and liver metabolism.

Conclusion

Sorbitol has long been considered a safe, low-calorie sweetener, but new research challenges that assumption. When sorbitol escapes the gut — either because too much is consumed or the microbiome cannot break it down — it can reach the liver and behave much like fructose, driving fat accumulation and potentially contributing to steatotic liver disease.

The takeaway is not that sorbitol must be avoided entirely, but that context matters. Diet quality, microbiome health, and overall sweetener consumption patterns all influence how the body handles sorbitol. As more research emerges, consumers may benefit from a more balanced approach to sugar substitutes, recognizing that “sugar-free” does not always mean risk-free.

Research Paper:

Intestine-derived sorbitol drives steatotic liver disease in the absence of gut bacteria