New Findings Reveal How Overactive Immune Cells Help HIV Persist Even Under Treatment

A new study from researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Institute of Human Virology (IHV) has shed light on a long-standing mystery in HIV science: why the virus manages to persist in the body even when antiretroviral therapy keeps it under control. The work identifies a key mechanism involving plasmacytoid dendritic cells, commonly known as pDCs, and shows how their overactivity weakens the immune system’s ability to clear HIV. These findings arrive from a research project led by Guangming Li, Ph.D., and Lishan Su, Ph.D., whose team published the study in Science Translational Medicine.

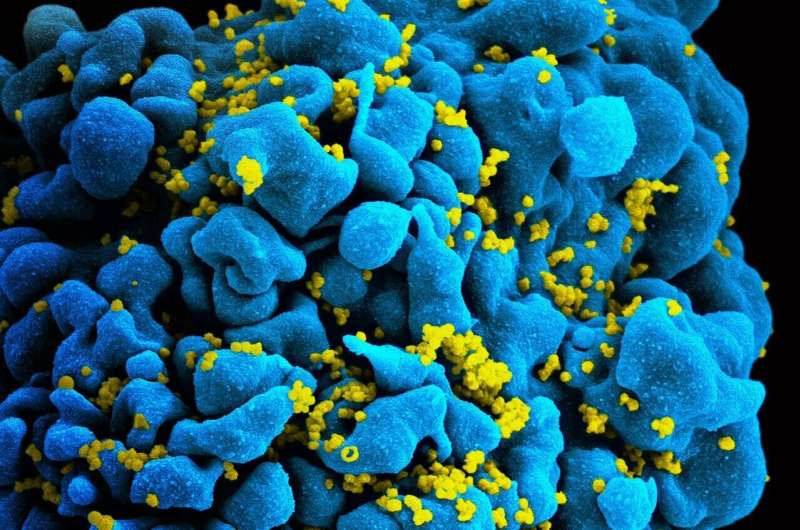

The researchers focused on pDCs because these cells act as an early alarm system in viral infections. When viruses appear, pDCs release large amounts of type I interferons—molecules that help coordinate the antiviral defense. Under normal circumstances, this response is essential. But the study reveals that during chronic HIV infection, pDCs remain in a constant state of activation, generating continuous immune inflammation that ends up doing more harm than good. This persistent activation creates an environment in which HIV can hide, survive, and subtly undermine immune cells designed to fight it.

Using humanized mouse models as well as blood samples from people living with HIV, the team tested what would happen if these overactive pDCs were reduced. In the mouse experiments, scientists used an anti-BDCA2 antibody to selectively deplete human pDCs from the spleen and other tissues. This reduction led to a significant improvement in the performance of antiviral T cells, which are essential for controlling HIV. Not only did T cells regain their ability to function properly, but the size of the viral reservoir—the pockets of hidden virus that remain in the body despite treatment—also shrank.

An even more notable result came when pDC reduction was combined with an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a type of therapy that reactivates exhausted immune cells. With both approaches used together, the immune response improved even further, offering a potential direction for future HIV therapies. While checkpoint inhibitors are more commonly used in cancer treatment, this study shows they may have a role in reshaping immune responses in chronic viral infections as well.

Researchers emphasized that pDCs and interferon responses are not simply harmful. They are critical for controlling viruses during early infection. The problem arises when this response becomes chronic, as is the case with HIV. This chronic inflammation can exhaust T cells, weaken viral control, and make it harder for the body to eliminate infected cells. Understanding this balance helps explain why people living with HIV often continue to experience immune activation even when their virus is well controlled with medication.

Although most of the findings came from laboratory environments and animal models, key observations were consistent when the team examined blood cells from individuals living with HIV. This strengthens the idea that managing pDC activity could be a valuable addition to strategies that aim to reduce or eliminate HIV reservoirs in humans.

The research team included contributions from Yaoxian Lou, a Ph.D. candidate, as well as scientists Shyamasundaran Kottilil and Poonam Mathur from IHV/UMSOM. Additional collaborators came from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Weill Cornell Medicine, highlighting the multi-institutional effort behind this work.

What Are Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells?

Since pDCs play such a central role in this study, it’s helpful to understand what they do. pDCs are a rare but essential immune cell type responsible for producing large amounts of type I interferons, especially interferon-alpha, during viral infections. These interferons alert nearby immune cells and help set off a cascade of antiviral responses.

However, the immune system relies heavily on balance. Too little interferon and viruses spread uncontrollably; too much interferon for too long, and the immune response becomes dysfunctional. Chronic overproduction is known to contribute to immune exhaustion, tissue inflammation, and weakening of specific immune responses. In the context of HIV, this overproduction appears to blunt the activity of CD8+ T cells, especially the stem-like CD8+ T cell subsets that are crucial for long-term viral control.

Understanding pDC behavior is increasingly important not only for HIV but also for other chronic viral infections and autoimmune conditions where interferon activity plays a significant role.

Why HIV Reservoirs Are Hard to Eliminate

One of the biggest obstacles to an HIV cure is the virus’s ability to establish reservoirs—small populations of infected cells where HIV hides in a dormant state. These reservoirs remain invisible to most immune responses and unaffected by standard antiretroviral therapy.

Even when the virus is not actively replicating, the reservoir remains ready to reactivate if treatment stops. The new study illustrates how chronic pDC overactivation may help these reservoirs survive by disrupting the immune environment that would normally help clear them.

Reducing pDC overactivity allowed T cells in the study to regain characteristics associated with effective antiviral responses, including the ability to proliferate and target HIV-infected cells more effectively. This provides a clearer understanding of how HIV maintains its foothold in the body and why addressing immune dysfunction is just as important as targeting the virus itself.

Implications for Future HIV Treatments

While this research is still in early stages, it opens several potential pathways for future treatment strategies:

- Adjusting pDC activity might reduce chronic inflammation in people living with HIV.

- Restoring T cell strength could improve long-term immune health and potentially reduce reliance on lifelong therapy.

- Combining pDC modulation with immune checkpoint inhibitors may offer a multi-layered therapeutic approach.

- Understanding how the immune system’s early responders shape chronic disease could inspire new immune-based therapies beyond HIV.

However, any therapy that reduces or suppresses immune cell populations must be tested cautiously. pDCs remain important for fighting infections, and their temporary removal must be proven safe before being explored in humans.

Researchers emphasize that further studies will examine whether adjusting pDC activity can be done safely in clinical settings, and whether these immune changes lead to meaningful long-term improvements in controlling HIV.

Research Reference

Depletion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells rescues HIV-reactive stem-like CD8+ T cells during chronic HIV-1 infection

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.adr3930