New Research Shows Pterosaurs and Birds Evolved Flight-Ready Brains in Completely Different Ways

A new study published in Current Biology offers one of the clearest looks yet at how ancient flying reptiles evolved the neurological tools needed for powered flight—and it turns out their brains followed a very different path compared to birds. Despite both groups becoming skilled flyers, their internal wiring tells two entirely separate evolutionary stories. This research brings together high-resolution brain reconstructions from dozens of extinct and living species and highlights just how diverse the journey to flight has been among vertebrates.

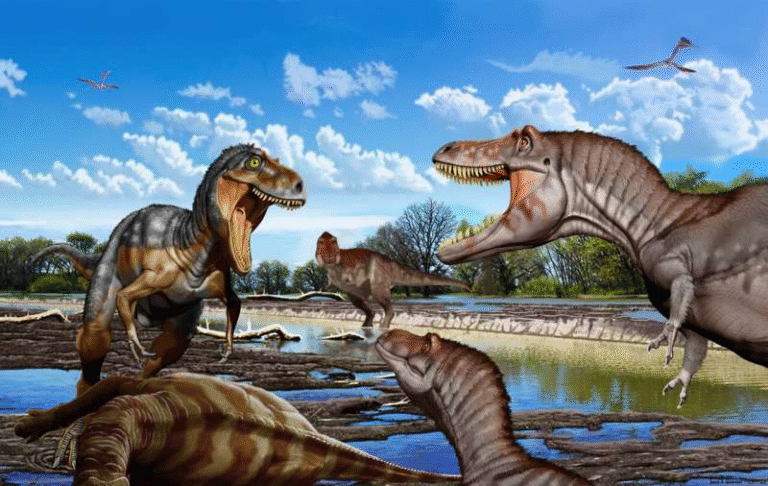

Powered flight is extremely rare in the animal kingdom. Among all vertebrates, it evolved only three times: once in bats, once in birds, and once in pterosaurs, which took to the skies more than 220 million years ago—long before the earliest birds appeared. While scientists have long understood how birds inherited their basic brain structure from their dinosaur ancestors, pterosaurs remained far more mysterious. Their brains seemed to appear suddenly and almost fully adapted for flight. The missing evolutionary steps were unknown.

That gap finally began to close with the discovery of Ixalerpeton, a tiny, tree-dwelling lagerpetid archosaur found in 233-million-year-old Triassic rocks in Brazil. Lagerpetids are close relatives of pterosaurs but were themselves flightless. This new fossil allowed researchers to map out which parts of the pterosaur brain evolved early and which traits appeared only once true flight developed.

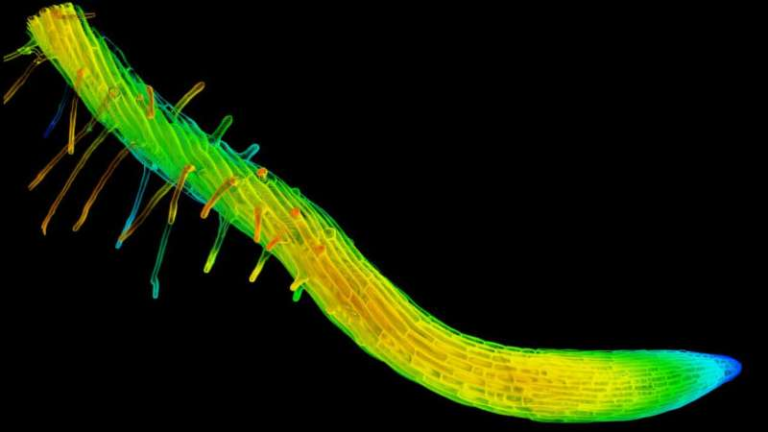

To dig deeper, the team used microCT scanning and 3D imaging to reconstruct cranial endocasts—digital models of brain shapes—from more than three dozen species, including early dinosaurs, modern birds, crocodilians, bird precursors, pterosaurs, and their closest relatives. From these digital brains, they analyzed the size and shape of key neurological regions to chart how flight-related changes emerged over time.

One of the most fascinating findings is that pterosaurs did not evolve large brains to take to the sky. In fact, their brains remained modest in size, especially when compared to modern birds. Birds developed relatively large brains, but that expansion happened gradually and was more closely tied to increasing intelligence, complex social behavior, and advanced sensory abilities—not the act of flying itself. This challenges the long-held idea that powered flight generally demands a big brain.

Pterosaurs instead focused on specific neurological specializations, especially in structures tied to balance, vision, and processing sensory feedback from their wings. A standout adaptation is the greatly enlarged flocculus, a part of the cerebellum that helps stabilize gaze and interpret sensory input from the flight membranes. This structure likely helped pterosaurs keep their eyes locked on targets while maneuvering through the air. Interestingly, birds also have a well-developed flocculus, but it appears to have evolved through a very different pathway.

Ixalerpeton helps clarify this picture. Its brain displays some features that later became important for flight in pterosaurs—most notably an enlarged optic lobe, hinting at enhanced vision. However, lagerpetids lacked the signature pterosaur traits, such as the expanded flocculus and the full suite of flight-ready sensory adaptations. Instead, their brains more closely resembled those of early dinosaurs, with only hints of what was coming later in true pterosaurs. This makes Ixalerpeton a key “transitional” species for understanding how flight-specific neural features evolved independently in different lineages.

Another noteworthy point is that the overall shape of pterosaur brains most closely matches that of small, bird-like dinosaurs such as troodontids and dromaeosaurids—species that had little or no powered flight ability. This resemblance is surprising because birds ultimately inherited flight from theropod dinosaurs, while pterosaurs developed it from an entirely separate branch of the archosaur family tree. Despite this, certain sensory and spatial-processing needs may have pushed both groups toward similar structural solutions, even though their evolutionary histories diverged sharply.

What makes this study especially valuable is its scale. By examining brain shapes across a wide range of both extinct and living animals, researchers were able to identify where pterosaurs and birds converged and where they remained unique. For example, both groups show larger optic regions compared to their ancestors—but only birds exhibit broad brain enlargement linked to cognitive complexity. Pterosaurs maintained smaller brains overall, but specialized in targeted neural modifications that supported aerial agility.

The study also highlights how much paleontological fieldwork continues to reshape our understanding of prehistoric life. Fossil discoveries from southern Brazil, especially lagerpetids like Ixalerpeton, are revolutionizing the picture of early archosaurs. Only a few decades ago, researchers had almost no direct evidence of the neurological precursors to pterosaur flight. Now, thanks to detailed field excavations and cutting-edge scanning technology, scientists can trace brain evolution in fine detail, filling in evolutionary gaps once thought impossible to reconstruct.

This research underscores a major takeaway: flight does not have a single evolutionary blueprint. Birds inherited a brain already trending toward higher intelligence and sensory integration, then adapted it further for flying. Pterosaurs, by contrast, evolved their brains and wings around the same time, building a functional flight system from the ground up. Their neurological adaptations were precise, efficient, and highly specialized for life in the air—even without the large brains seen in birds.

For readers interested in the broader context, it’s helpful to know that this study fits into a long line of research exploring how flight reshaped sensory and cognitive evolution. In birds, large brains are often linked to problem-solving abilities, social behaviors, and learning—traits that became increasingly important long after flight began. Pterosaurs, meanwhile, dominated the skies for more than 150 million years with a different strategy: optimizing sensory systems related to flight while keeping overall brain size relatively small.

This difference also hints at variation in lifestyle. Birds eventually diversified into forms with complex social structures and behaviors such as vocal learning, tool use, and coordinated flocking. Pterosaurs, although extremely diverse in size and shape—from tiny species to giants with wingspans over 10 meters—did not show the same cognitive expansion. Their evolutionary priorities were different, shaped by ecological needs rather than increasing intelligence.

Studies like this demonstrate how multiple evolutionary solutions can emerge for the same functional challenge. The fact that birds and pterosaurs evolved successful, long-term flight through such different neurological paths is a reminder of evolution’s flexibility. It also provides a richer understanding of how sensory systems, brain anatomy, and physical structures influence each other over millions of years.

As more fossils are found and new scanning techniques continue to improve, scientists expect even clearer insights into how ancient animals developed complex capabilities such as flight. For now, this research gives us the best glimpse yet into the early stages of pterosaur brain evolution—and shows how much more there still is to learn about the history of life in the skies.

Research paper:

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(25)01467-8